Before being closed down by the Federal Trade Commission, a revenge porn site called “Is Anyone Up” came up with a creative but disgusting twist on the sleazy genre by including a link to a phony “independent third party team” that would get the offensive pictures taken down for a fee.1 In other words, the site and its proprietor horribly violated peoples’ privacy and then extorted them for money to stop violating them. That sick scheme provides a perfect lead-in to a discussion of the San Diego Chargers and the recently announced joint stadium proposal made by the Chargers and the Oakland Raiders that would involve both teams leaving their current cities and moving to the Los Angeles area.

After long claiming that it would issue no ultimatums to the City of San Diego, the Chargers have combined with erstwhile bitter rival the Oakland Raiders to announce that rights to land in Carson (just south of Los Angeles, 100 miles north of San Diego) had secretly2 been obtained for a joint use stadium to be built there at a cost of $1.7 billion with no public expenditures whatsoever. The video announcement (shown above) is as up-beat and promising as you’d expect, even if the announcement press conference was more than a bit amateurish, consistent with the local government in Carson generally, and was not supported by anybody from the teams.3

This news was a major surprise to San Diego and to fans of the team. San Diego’s mayor found out about it from the press – not the Chargers — even though both sides had met about a stadium in San Diego just three days before. Even so, the Chargers still assert that the team is committed to trying to work out a plan to keep them in America’s Finest City, home to the Chargers for over 50 years (the team played its first AFL year in Los Angeles in 1960 before moving south).

This news was a major surprise to San Diego and to fans of the team. San Diego’s mayor found out about it from the press – not the Chargers — even though both sides had met about a stadium in San Diego just three days before. Even so, the Chargers still assert that the team is committed to trying to work out a plan to keep them in America’s Finest City, home to the Chargers for over 50 years (the team played its first AFL year in Los Angeles in 1960 before moving south).

Meanwhile, Carson officials promised nearly everything short of a cure for cancer – thousands of union jobs, a “green build,” no usage of city general funds or taxes and reliance entirely upon revenue generated by stadium events to fund the project. It has even been reported that Chargers’ investment bank Goldman Sachs will finance the team’s prospective move to Los Angeles, including covering any operating losses suffered by the team in the first few years in that city as well as costs for any renovations needed in a temporary venue. Surely, LA offers more potential opportunity for any NFL team that moves there than San Diego can. That said, even many in Los Angeles think the Carson proposal sounds more than a little fishy and previous LA pro football teams left due to a lack of support and sweetheart deals elsewhere. But perhaps the NFL has become such a big deal over the 20 years since Los Angeles last had an NFL team that the City of Angels will indeed support one or even two new NFL teams going forward.

Chargers special counsel Mark Fabiani, chief spinmeister on stadium issues for the team since 2002, told ESPN that the model for the Carson project is the $1.3 billion stadium built for the San Francisco 49ers in Santa Clara, south of the city: “We took the template of the Santa Clara funding mechanisms … so we basically took that and adjusted it for different costs here.” A representative of Goldman Sachs, the investment banker on that project as well as for the Chargers, echoed this idea at the press conference. The 49ers opened this new, privately financed stadium last year and it is generally considered a financial success.

According to the statement released by the teams, the Chargers and Raiders will continue to seek public subsidies for new stadiums in their home markets, but they are developing a detailed proposal for a privately financed Los Angeles venue in the event they can’t get deals done in San Diego and Oakland by the end of this year. Since the $1.7 billion cost estimate is an initial one, the actual cost will likely be significantly higher too. Even worse, team flack Mark Fabiani has conceded that the Chargers are prepared to go it alone in Carson and still wouldn’t require public assistance while calling for tax increases to pay for a new stadium in San Diego.

As The New York Times has reported, Los Angeles being an apparent rival for a team’s affections has been an extremely lucrative proposition for the NFL and its owners. In recent years, politicians have committed $670 million in public funds to the Indianapolis Colts’ new stadium; $498 million to the Minnesota Vikings’ new home; $471 million to the Superdome, home of the New Orleans Saints; $226 million in renovations to the Buffalo Bills’ stadium; and $43 million in upgrades for the Jacksonville Jaguars — all amid whispers that the teams might move to Los Angeles.

The Carson announcement is an obvious attempt (a) to compete with a recent (competing) proposal to move the St. Louis Rams to Hollywood Park, and (b) to put pressure on San Diego (and Oakland). It was at least successful in sending shockwaves throughout America’s Finest City, and not just at the idea of the Chargers and the hated Raiders working in concert. The Chargers have been trying to get San Diego to ante up for a new football stadium for 14 years (seven mayors and nine proposals amidst major dysfunction) without success. Both the Chargers and the Raiders have long claimed that they aren’t nearly flush enough to build stadiums in their home cities without huge public subsidies. Any such public financing plan would require approval by two-thirds of voters and most polls have indicated that even though people want the team to stay in San Diego, most local residents oppose paying the Chargers to stay.

The Los Angeles play has surely gotten San Diego’s attention,4 despite (because of?) what San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer calls the team’s “sneaky, rude and duplicitous” behavior. More than a week later it still dominates local sports radio and is the subject of daily newspaper coverage. Of course, Qualcomm Stadium is truly a dump (Time magazine ranked it 4th worst in the USA across all sports and only one of the three rated worse will be used for professional sports after this year).

As noted, the Carson proposal’s lack of a public contribution component is in sharp contrast to the position the Chargers have taken with San Diego. Most estimates have placed the cost of a new stadium in San Diego to be at least a billion dollars, with the possibility that costs could come in at around $1.5 billion or even more. The Chargers have consistently insisted that San Diego contribute roughly 60 percent of that cost, perhaps more. The team has offered no equity (or even naming rights) in return for such an immense financial commitment – from $600 million to a billion dollars or more.

To be fair, governments often do offer incentives – corporate welfare – to companies to convince them to come or to stay. But such incentives typically come in the form of tax breaks, not cash, and are far smaller than what the Chargers are demanding. For example, Connecticut recently provided UBS with a $20 million forgivable loan to keep the global investment bank and its 3,500 employees (the Chargers employ fewer than 200 people overall, including players and coaches) from moving to New York City. Here in San Diego, our world-famous zoo gets $10.2 million a year via a special property tax, $16.1 million is spent annually on Petco Park for the Padres, and the City spends $15.8 million per year on the current football stadium.

To put my own cards on the table, I am a football fan and was a Jets season ticket holder years ago when I lived back east and was a Chargers season ticket holder before I gave up my seats to attend my son’s (then) PAC-10 football games. Since his playing career ended (due to injury), I have remained a La-Z-Boy fan of the Bolts who attends games in-person on occasion. All in all, I would very much like the Chargers to remain in San Diego.

The Chargers have consistently argued that fans need to look at the stadium question as a business matter, especially because the team fears losing 25 percent of its revenue if another team or teams moves to Los Angeles.5 So let’s do that.

1. The Background.

The current stadium was built in 1967 and has been expanded and refurbished in 1984 and 1997. The 1997 renovation cost nearly $80 million and was based upon assurances by the Chargers that doing so would meet the needs of the team for years to come and allow San Diego to host the Super Bowl in 1998 and to remain in the Super Bowl rotation. Just three years later, owner Alex Spanos claimed the team needed a new stadium and San Diego was subsequently removed from the rotation of Super Bowl sites (the last San Diego Super Bowl was in 2003). More recently, the rotation plan was scrapped as other cities with new stadiums have gotten to host Super Bowls. Without a new stadium, San Diego will remain out of that loop. In 2004 the Chargers asked for a new stadium that would cost “just” $400 million. The Fed’s inflation index for non-residential construction suggests that same stadium should cost no more than $600 million today, but teams increasingly want more and more expensive “bells and whistles” in new stadiums, especially when someone else is paying for them.

2. Public Assistance to Pay for a New Football Stadium Makes No Economic Sense.

Since at least the construction of the Los Angeles Coliseum in the 1920s, the public purse has played a major role in getting sports stadiums built in the United States. However, despite constant claims to the contrary, there is no longer any viable argument that sports stadiums make financial sense for local governments. See, for example, articles here, here, here (“When political ‘games’ are played in governmental places – city halls, state legislatures, even in the halls of Congress – the participants risk causing injury to the public treasury and to the public welfare”), here and here; see also the following book-length treatments: Field of Schemes; The King of Sports; Public Dollars, Private Stadiums: The Battle over Building Sports Stadiums; They Play, You Pay: Why Taxpayers Build Ballparks, Stadiums, and Arenas for Billionaire Owners and Millionaire Players; and Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums.

For a representative sample of the conclusions of these studies, consider the following (from here). “The principal argument in support of public subsidies for private enterprise, including sports stadiums and arenas, is that such expenditures create local jobs and spur economic redevelopment. However, virtually all economists who have studied the issue in the sports context have concluded to the contrary.” Gregg Easterbrook, who moonlights as ESPN’s Tuesday Morning Quarterback, lays out the sordid details in The Atlantic here. Reason magazine goes so far as to say that no smart city should want the NFL.

Andrew Brandt of Sports Illustrated’s Monday Morning Quarterback summed it up nicely (emphasis in original). “NFL owners have never been above forging the best deal possible for themselves. Wealthy NFL owners do not ‘need’ their local municipalities to help finance state-of-the-art stadiums (nor did they ‘need’ a better deal with the players in the most recent CBA). However, they negotiate favorable terms because, well, they can.”

3. The Chargers Can Afford to Build a New Stadium Without Public Assistance.

By most accounts, the Chargers are worth about a billion dollars in San Diego. The Spanos family purchased 60 percent of the team in 1984 for nearly $50 million and later acquired the remainder for a total purchase price of about $70 million. Assuming the billion dollar valuation is accurate, that’s an annualized return on investment of about 9.5 percent. Since such estimates are generally low and often really low (never underestimate the willingness of billionaires to bid for trophies of various sorts — see below), the team is probably worth a lot more than that and thus investment returns on owning the Chargers have likely been significantly higher (more on that below).

According to Forbes, the Spanos family has a current net worth of $1.3 billion. Moreover, since television revenue alone amounts to roughly $200 million per year while player costs – by far the team’s biggest expense – total well less than $150 million annually, the Chargers are immensely profitable with remarkably little risk. According to Vanderbilt University economist John Vrooman and Vrooman Sports Economics, current operating profits are roughly $75 million per year. Current corporate debt is minimal (about 10 percent). Full details are unavailable since the team does not release its financials, necessitating the use of estimates. That said, since the team is unwilling to show any real need by revealing financials, I assume that its financial status is at least as good as estimates suggest. If I’m wrong, the team can demonstrate it, but none of us should take anyone’s word for it.

Most estimates suggest that club seating and luxury boxes would generate an additional $50 million in annual revenue, on top of current estimates of over $100 million per annum, and would generate an additional $25 million in operating profit. Private seat licenses could be another source of revenue (PSLs at the new Levi’s Stadium in San Francisco generated $550 million for the 49ers; Vrooman estimates $300 million could be generated in San Diego, which does not have the wealth of Silicon Valley) as would naming rights (Levi’s is paying $220 million over 20 years). The Chargers have suggested that the stadium be financed through higher taxes, among other means. Meanwhile, San Diego has huge unfunded pension and infrastructure deficits (John Oliver examined national infrastructure needs on Sunday’s Last Week Tonight).

According to Vanderbilt University economist John Vrooman and Vrooman Sports Economics, the various options stack up as follows.

Annual debt service on any stadium project will vary, obviously, based upon the project, the amount borrowed and the terms of the deal. A stadium wouldn’t be financed in this way, but a 20-year amortizing loan at 5 percent interest on $600-$1 billion would cost roughly $50-$80 million annually, which provides a very rough benchmark for discussion purposes. The local newspaper estimates that annual debt service on $600 million would run to about $32.2 million, slightly more than the amount that is spent on garbage collection. In any event, the Spanos family can almost surely afford to build a new stadium in San Diego without public assistance. Profits appear more than sufficient to cover debt service. Normal growth projections for the team and the NFL offer even less reason to think otherwise.

Annual debt service on any stadium project will vary, obviously, based upon the project, the amount borrowed and the terms of the deal. A stadium wouldn’t be financed in this way, but a 20-year amortizing loan at 5 percent interest on $600-$1 billion would cost roughly $50-$80 million annually, which provides a very rough benchmark for discussion purposes. The local newspaper estimates that annual debt service on $600 million would run to about $32.2 million, slightly more than the amount that is spent on garbage collection. In any event, the Spanos family can almost surely afford to build a new stadium in San Diego without public assistance. Profits appear more than sufficient to cover debt service. Normal growth projections for the team and the NFL offer even less reason to think otherwise.

Looking forward, it’s important to note that franchise values have continued to escalate sharply. And given the recent $2 billion sale price of the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers (more than double what Forbes had valued the team at a year ago and consummated well after the Forbes valuation of the Chargers), based largely upon the fantastic growth in the value of live sports to advertisers (who don’t want to pay for you to fast-forward through the commercials on your DVRed shows) and the “trophy value” sports teams offer to billionaires (in some cases so they can treat their teams like stupid fantasy owners do), the $1 billion valuation for the Chargers looks way too low. Note that the Clippers have revenues far lower than the Chargers ($146 million to $262 million; operating income of $20 million to $40 million). Of course, Forbes values routinely turn out to be very low when teams actually change hands. Remember that analysts thought Jerry Jones was crazy for paying $140 million for the Dallas Cowboys in 1989, an amount that in retrospect is seen as “a fire-sale price.”

The bottom line here is that the Chargers can well afford to build a stadium without the public paying for it or any part of it and would still be very profitable, especially if and as the NFL’s trendline of success continues. But the team may not be as profitable as the Los Angeles Chargers would be. Nobody should feel sorry for the Spanos family, but the Chargers are on the lower end of the NFL financial totem pole. A move north could change that.

After more than 50 years in San Diego, a town that has largely supported the Chargers well and which has made team owners a considerable fortune (despite a spotty — at best — success record on the field and no championships), the Chargers propose moving to Los Angeles because of the possibility of earning more money. The owners of the Chargers can afford to pay for their own stadium in Los Angeles and they can afford to pay for their own stadium in San Diego. The team is getting no financial incentives from the public to move yet is demanding hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to stay.

So let’s call the play what it really is: extortion, bribery and corporate welfare. It’s perfectly legal, of course, and the Spanos family is entirely within its rights to try to maximize profits and even to leave the city and the fans that have helped to make them immensely rich for what might turn out to be a better deal to the north. We like to think of the professional teams we support as ours, but they aren’t. They are businesses. To the extent that they wish to maximize profitability, fan interests are irrelevant except to the extent that those interests impact profitability. It should be crystal clear at this point that the Chargers are in no way our team; the team and its future belongs utterly and inexorably to the Spanos family.

The economic analysis is clear; it makes no investment sense to give in to the team’s shakedown efforts. Moreover, the Carson proposal looks sufficiently half-baked that the threat of leaving, while getting the predictable response on talk radio, may well be a bluff (indeed, a number of pundits, even in LA, see it as a bluff) and a bluff that ought to be called.

4. Other Considerations.

But none of us who support the Chargers should doubt that the team’s threat to leave may be a real one. It may be a shakedown, but if we don’t pay (or pay enough) the team may well leave. Thus, San Diego could decide that there are sufficient other benefits to having an NFL team to justify paying off the Chargers to keep the team here even though it doesn’t make sound economic sense. Indeed, the lack of financial sense undergirding public stadium financing generally has caused proponents to shift focus to what Malcolm Gladwell calls “psychic benefits.” San Diego may well want to be perceived as being a “big league” city. Politicians may not want to be branded as having let the team go. Despite what the polls suggest, enough fans may be supportive to justify paying the Spanos family to stay. The idea that a stadium is a valuable public good may be enough to justify the cost (or, more likely, some cost) despite the lack of more tangible benefit. But even so, a stadium remains a lousy investment. As with the 2008 bail-outs of the big banks during the financial crisis, the Chargers want the public (in this case, San Diego residents) to bear the major costs and essentially to eliminate the team’s financial risks while foregoing the financial rewards of the “investment.”

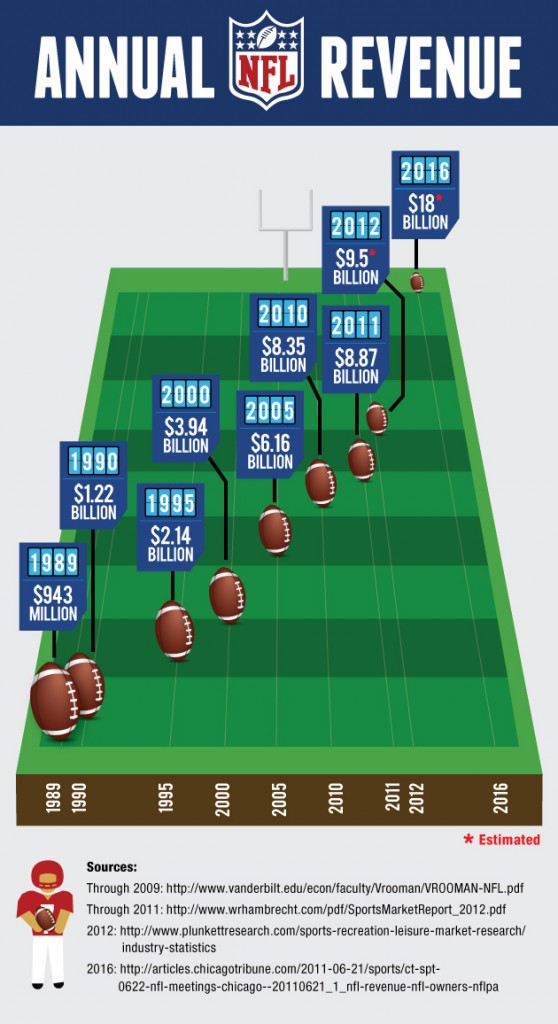

Despite some pretty smart dissenters, and an argument that the current level of revenue growth is unsustainable, football has been an astonishingly lucrative business endeavor (see below).

The current proposal from the Chargers with respect to San Diego is designed expressly to enrich the team and its owners at the expense of taxpayers and without any opportunity for taxpayers to share in any future growth. That’s just the reality of things.

In addition to San Diego’s need to decide how much the Chargers are worth keeping, team ownership needs to decide whether the psychic benefits of keeping the team in town are worth the potential for being a little less obscenely rich than a Los Angeles franchise might allow. The Chargers claim that the Carson option is necessary “for one straightforward reason: If we cannot find a permanent solution in our home markets, we have no alternative but to preserve other options to guarantee the future economic viability of our franchises.” Since the Chargers have been, remain and will continue to be immensely profitable for the foreseeable future, the idea that the team’s “future economic viability” is somehow in doubt is obviously false.

The Spanos family can continue to make huge amounts of money here in San Diego and can establish a remarkable legacy by staying here and resisting the potential for even greater riches in Carson. Or the Spanos family can insist on maximizing profits, loyal local supporters be damned. It’s entirely up to them … not us. The question remains, however, how much extortion money should be paid in order to keep the Chargers around.

___________

1 In an astonishing bit of irony, after the FTC barred him from publishing nude images of people without their consent, the proprietor of that site has tried to get Google to remove links to news accounts about the FTC’s action and other related stories citing “unauthorized use of photos of me and other related information.”

2 Just last month, Chargers special counsel Mark Fabiani disputed a report that the team was partnering with Goldman Sachs to fund a stadium in Los Angeles, saying “although we have worked for years with Goldman Sachs as our investment banker, the remainder of the story is untrue.” When the Carson project was announced, San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer was upset that despite having met with Chargers’ officials three days before, he first heard about the proposal from the press.

3 Chargers special counsel Mark Fabiani was there, but he did not speak.

4 Clearly, whatever else is true, the Carson proposal has gotten San Diego’s attention. A Citizens’ Stadium Advisory Group was recently created by the Mayor to come up with a stadium proposal. This task force held a public forum last night at Qualcomm Stadium attended by a couple thousand to hear from citizens on the stadium issue. A “Save Our Bolts” rally was held there too. All the local media outlets were there, the event was streamed live by the local newspaper while three radio stations broadcast the proceedings live.

5 Besides the Chargers/Raiders joint venture, the St. Louis Rams owner Stan Kroenke also has a plan to move to Los Angeles (Inglewood). Details about the current stadium arrangement are available here.

This is a very detailed and enlightening article about what is essentially an old-fashioned shakedown operation. Being an LA guy, I want to note that the city’s support if the Rams was top-notch until Carroll Rosenbloom and later his bimbo widow started mismanaging the team, moving it from its fanbase in Los Angeles County (what most Angelenos mean when they say “LA”) to Orange County, effectively cutting off support from the West Side and the northern San Fernando Valley. Then, when the team was less successful in the Big A than in the Coliseum, the Bimbo started selling off assets and eventually sold the team to the highest bidder, St Louis, thieve of sports franchises (they will make a run for the Bolts, too, if LA doesn’t pan out — and by the way, no one I know here wants to steal your team.) I would say do what LA has done for several decades, so no to the bastards, but the price for that may be loss of the team. Still, I can’t see Spanos trading down for St. Louis or even trading for a fraction of LA when he can have San Diego, which is a very nice city even if it isn’t the best city in the country.

Sounds about right to me (much as I’d like the Chargers to stay). Thanks for reading and commenting.

I would be interested to learn the taxation of the NFL, NFL Properties, and any special breaks or treatment that they receive in running their businesses. It seems incomprehensible to have Americans subsidize a sport when roads are crumbling, educations do not prepare kids adequately, and our nation in in debt to foreign entities that attack us whenever they choose.

The article I sited and linked from The Atlantic (which is a book excerpt) provided that information. You might start there.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

How about them Padres? And the Gulls are coming back!

This is a very well written article; I have to admit. Thanks for sharing