S&P’s decision to downgrade the debt of the United States was understandably controversial. But it was right.

INTRODUCTION

Standard & Poor’s recently downgraded the credit rating of the United States by one notch for the first time in the history of its ratings. With respect to sovereigns specifically, per S&P: “Sovereign credit ratings reflect Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services’ opinions on the future ability and willingness of sovereign governments to service their debt obligations to the nonofficial sector in full and on time.”

The symbolic difference between AAA and AA+ may be great, but the substantive difference is not. As described by S&P, “[a]n obligation rated ‘AA’ differs from the highest-rated obligations only to a small degree. The obligor’s capacity to meet its financial commitment on the obligation is very strong.”

With respect to the downgrade, therefore, the appropriate question is whether S&P is correct that the U.S. is or can reasonably be expected to be slightly less able or willing to pay its obligations going forward. In my estimation, the answer to this question is clearly “Yes.”

ANALYSIS

Criticism of S&P’s actions has centered upon three main contentions.

- S&P has no credibility[1];

- There is no question as to the ability of the U.S. to pay its obligations[2]; and

- S&P has no business evaluating political risk (a sovereign’s willingness to pay).[3]

Let’s look at these contentions in turn.

1. S&P Credibility

S&P and all of the ratings agencies have been under significant pressure since at least the 2008-2009 financial crisis when they rated dangerous securitized mortgage-backed paper as AAA while being paid enormous fees for doing so by the sponsoring banks. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission claimed that S&P and Moody’s were “key enablers of the financial meltdown.” A Senate panel accused the ratings agencies of engaging in a “race to the bottom” to assign top grades on sub-prime securities in order to win fees from banks. The Justice Department is now said to be investigating S&P for improper conduct in rating these securities.

The agencies also missed the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, missed the AIG collapse and are still struggling to handle mortgage debt properly. Moreover, S&P didn’t downgrade Ireland (once AAA) until long after its financial problems had become obvious and the price to buy insurance on its debt had increased tenfold from a year earlier. Its dealings with Greece were similar. And, don’t forget, Enron and WorldCom were once AAA. Some go so far as to suggest that ratings agencies have surpassed their usefulness and that they ought to be ignored.

Moreover, the S&P process is not a transparent one, and the ratings agencies as a whole have a poor record of predicting sovereign defaults. Indeed, S&P’s ratings have not performed very well (as Nate Silver does a good job pointing out here) even as a general indicator of future financial health. As a consequence, the SEC is weighing sweeping new rules designed to improve the quality of ratings in light of their poor performance during the financial crisis. Of course, S&P vigorously opposes such changes and, on August 8, issued an 84-page letter of protest. S&P has also balked at an SEC proposal to reveal ratings errors. Not surprisingly given the controversy over the downgrade, S&P President Deven Sharma has announced that he is stepping down.

S&P did not help its credibility during its review of the U.S. credit rating by making a major analytical error with respect to debt calculation. Immediately after the downgrade announcement, a source familiar with the discussions said that the Obama administration had demonstrated that the original S&P analysis contained “deep and fundamental flaws.” The Treasury’s official response to the S&P downgrade made that point and showed that S&P had indeed made a mistake in its debt-sustainability calculations. Accordingly, Treasury claimed that “the credibility and integrity of S&P’s ratings action” must be called into question.

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner claimed that the “S&P decision to cut U.S. credit rating shows stunning lack of knowledge about basic U.S. fiscal budget math.” He also accused S&P of “terrible judgment.” Of course, this is the same Tim Geithner who had earlier proclaimed that there was “no risk” of such a downgrade. The Senate Banking Committee is looking at reviewing the downgrade, which Committee Chair Tim Johnson called “irresponsible.”

S&P responded with a statement that conceded the error and lowered its forecast for the U.S. debt-to-gross domestic product ratio in 2015 by two percentage points. S&P’s original calculations showed net general U.S. government debt hitting 93% of gross domestic product in 2021. The corrected figure is 85%. However, while S&P did remove a prominent discussion of the economic justification from its analysis, it also stated that these revisions did not change its decision to affect the downgrade.

The magnitude of this error is particularly noteworthy in that the original 93% figure and the corrected 85% figure bracket the economic and policy guidance offered by economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, authors of the outstanding This Time is Different. Their work showing how countries that reach a 90% ratio slide into recession and see slowing growth well before that has become increasingly important in this area. The current level in the U.S. per S&P is 74% and, as noted above, will rise to 85% (but not 93%) by 2021. S&P’s rationale for the downgrade closely tracks the Reinhart/Rogoff logic, even after the correction. Had S&P been able to establish a move to 90% or above, its case would have been much cleaner and easier to make in light of this influential research.

But whatever else is happening here, by refusing to accept an issuer’s approach, rationale and models (in this case, the issuer is the United States), S&P is not repeating its past mistakes. Indeed, on account of S&P’s past issues and damaged reputation, we should not be surprised when its ratings decisions are biased toward making sure it does not miss future problems. S&P’s downgrade decision should be evaluated strictly on its merits and not based upon past problems.

2. U.S. Ability to Pay

At the most straightforward level, the U.S. need never default on its debt because it can simply print money to pay it off. But that is not the only appropriate credit consideration. Relative credit weakness matters and the U.S. is decidedly weaker today from a financial standpoint than it has been in the past. The ability of the U.S. to pay its debts has been compromised in a very real – if not crippling – sense.

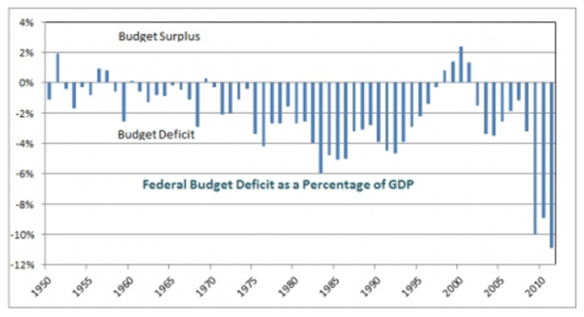

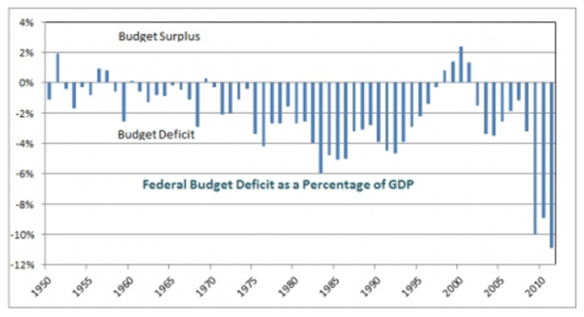

U.S. gross debt stands at $14.5 trillion and unemployment is 9.1%. Except for a brief period at the peak of the business cycle around the turn of the century, deficits have been a constant for decades, as shown below.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Federal revenue has fallen substantially over the past several years for a variety of reasons (I detailed them here), exacerbating the problem. Receipts are far short of revenues, as illustrated below.

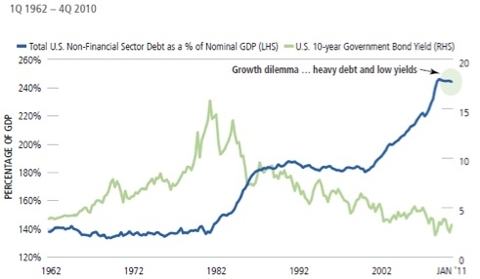

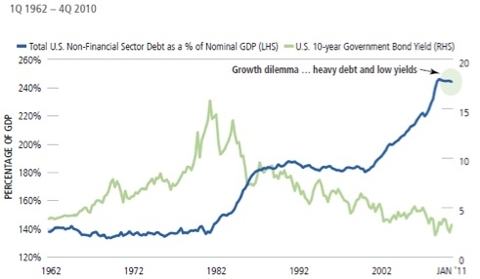

Revenue was 14.9% of the economy in 2009 and 2010, the least since 1950, according to the Office of Management and Budget. At the same time, total U.S. debt generally and as a percentage of GDP has grown substantially, as illustrated below for the period from 1962-2010.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Bloomberg

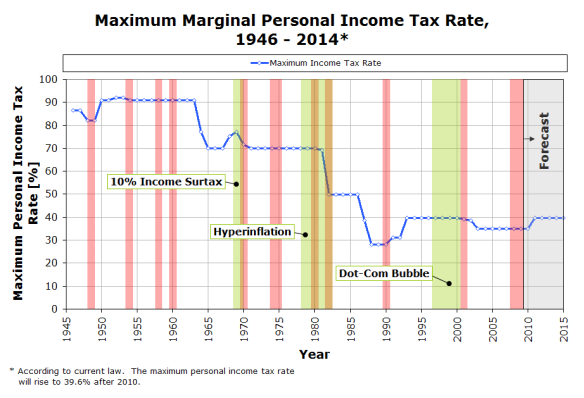

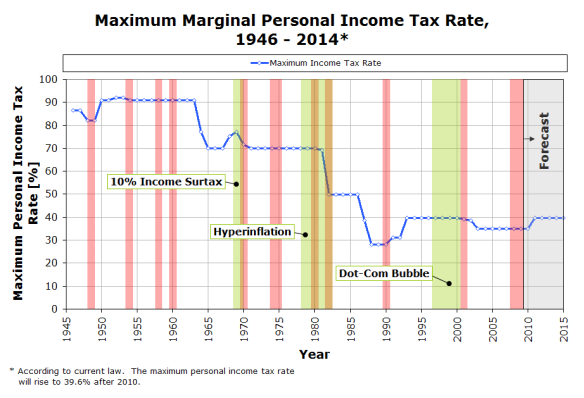

Until recently, post-WWII tax revenue had tended to hold fairly steady at about 19.5% (“Hauser’s Law”) irrespective of the highest marginal tax rates (see below, from Political Calculations).

Accordingly, the current figure of less than 15% is a dramatic decline. The recent debt ceiling deal provided for almost no immediate debt relief and surprisingly little relief longer term (more here), as shown below. The economic problems described by S&P are real, substantial and growing.

As noted above, S&P projects that U.S. debt will reach 85% of gross domestic product within a decade. According to S&P, that debt level approaches an “inflection point on the U.S. population’s demographics and other age-related spending drivers,” so as to accelerate potential problems. S&P notes that the debt agreement “envisions only minor policy changes on Medicare and little change in other entitlements, the containment of which we and most other independent observers regard as key to long-term fiscal sustainability.” Per the CBO: “The retirement of the baby-boom generation is a key factor in the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook. It portends a significant and sustained increase in the share of the population receiving benefits from Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.” The debt problem is obvious and growing and there seems to be no limit on the federal government’s desire both to enlarge the problem and to push it into the future and onto future generations.

I do not doubt that U.S. bonds are money good. But that does not mean that the ability of the U.S. to pay its debts has not been impaired. Even so, despite the obvious financial issues, it is unlikely that S&P would have downgraded the U.S. without the political problems highlighted in its report.

3. Evaluating Political Risk

I worked on a landmark $1 billion Chinese government global bond deal in 1994. The deal did not go well. To be fair, it struggled for a variety of reasons. The Fed was tightening and interest rates were rising. The managers of the deal (including my firm) wanted it to price at an extremely tight level to show what great execution they could get so as to obtain future deals and future business from the Chinese. Indeed, the deal priced at too tight a level and the managers were stuck with a lot of bonds and lost a lot of money (but they did end up getting a lot more business later).

A significant (if largely unexpressed) reason for the deal’s problems was political risk, a type of risk that is exceedingly difficult to quantify since it is predicated not upon financial realities, but upon the whims of people. There was no real concern about China’s ability to make good the bonds. Even then, China’s economy had great potential and the government had substantial assets. The problem was not really China’s political stability (or lack thereof). Nor was it a hangover from the 1989 protest and massacre in Tiananmen Square (although some were nervous about a recurrence).

At that time, the Chinese had not had a great deal of international capital markets experience, and the experience they had did not bode well for the future. You see, in a few relatively minor transactions that didn’t go their way, the Chinese had shown an unfortunate willingness to walk away without paying Wall Street as agreed. The problem was not ability to pay, it was willingness to pay.

Unlike other ratings agencies, S&P’s approach emphasizes subjective considerations about a country’s political environment, and is much criticized as a consequence. That approach, while difficult to implement, makes perfect sense. As a creditor, my debtor’s cash position means absolutely nothing if that cash is not used to pay the obligation owed to me in full and on time.

The S&P statement is clear that political risk was crucial to the downgrade decision:

“The downgrade reflects our view that the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions have weakened at a time of ongoing fiscal and economic challenges….

“[W]e have changed our view of the difficulties in bridging the gulf between the political parties over fiscal policy, which makes us pessimistic about the capacity of Congress and the Administration … to leverage their agreement this week into a broader fiscal consolidation plan that stabilizes the government’s debt dynamics any time soon.

“The political brinksmanship of recent months highlights what we see as America’s governance and policymaking becoming less stable, less effective, and less predictable than what we previously believed. The statutory debt ceiling and the threat of default have become political bargaining chips in the debate over fiscal policy. Despite this year’s wide-ranging debate, in our view, the differences between political parties have proven to be extraordinarily difficult to bridge.”

As The Economist points out, “whatever the flaws in its financial logic, S&P’s political analysis is spot on. … The agency says that its decision was based not only on the modesty of the savings contained in the final deal hammered out by Republicans and Democrats but also on the way the agreement was reached.” As Elizabeth Drew summarizes:

“This country’s economy is beset with a number of new difficulties, among them that recovery from the last recession remains more elusive than was generally expected, while the US is confronting a variety of international economic instabilities, especially the large debts and possible default of several countries in the [E]urozone, bringing on unpopular austerity measures. Recent experience with what should have been a simple matter of raising the debt ceiling, normally done with no difficulty, is reason for deep unease about our political system’s ability to deal with such challenges.”

The failures of the recent debt ceiling debate are hardly new, if more obvious and more intense. For example, as recently as last year the Simpson-Bowles Commission was appointed by President Obama to great fanfare, deliberated for a number of months, and provided a careful (if controversial) outline designed to identify “policies to improve the fiscal situation in the medium term and to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long run.” It has been unceremoniously ignored by essentially everyone. S&P’s decision represents its calculation that the ongoing debt problem, coupled with increased political discord such that a solution to the debt problem over the near to intermediate term is unlikely, merits the downgrade.

As Felix Salmon points out, “S&P and Moody’s can look at all the econometric ratios they like, but ultimately sovereign ratings are always going to be a judgment as to the amount of political capital that a government is willing and able to spend in the service of its bonded obligations. If Treasury really believes that S&P based its judgment fundamentally on debt ratios and the like, it’s making a basic category error about what it is that sovereign raters actually do.”

Simply put, a majority in Congress (consisting of members of both parties) has been and remains unwilling to require the federal government to live within its means[4] over the long-term while the President cannot or will not do anything about it.[5] At the same time, a (different but still) majority in Congress (consisting of members of both parties) has been and remains unwilling to enact tax legislation sufficient to pay for the spending it has authorized while the President cannot or will not do anything about it.[6] Democrats who complained loudly about budget deficits during the (most recent) Bush administration are silent now while Republicans who failed to criticize deficits during those years[7] are vocal about them now. Finally, and perhaps most tellingly, there is little reason in the current political climate to expect one side to compromise if there is a significant chance that credit for any subsequent benefit will be attributed to the other side. Today, political positioning seems to take precedence over the national interest far too often.

Meanwhile, neither stimulus nor qualitative easing appear to have not helped much to this point and, given the amount of debt already incurred, further action is not likely to help. As I noted here, I agree with Ken Rogoff that the answer lies elsewhere[8] and that a different approach is needed.[9]

There is also little left in the Fed’s toolbox now that it has pledged for the first time to keep its benchmark interest rate at a record low at least through mid-2013. Stimulus policy has a chance to work when governments have the capacity to take on more debt without harm. But we may well be past that point now. Additional debt will likely create further problems that will result in a bigger crisis later.

The actions of the U.S. government suggest that its highest ideal is “kicking the can down the road” as long as possible. Irrespective of who has the better case to make, Republicans are clearly inclined to reduce debt but will not authorize additional revenues and appear to have the votes to maintain that approach. At the same time, Democrats are clearly inclined to maintain current programs without reduction. Indeed, there is little reason to suspect that if the Democrats prevailed and negotiated a delay in dealing with U.S. debt in order to deal with what they see as more pressing matters (which, in the current political climate, is not going to happen), that they would actually deal with the debt problem after the crisis passes. Classic Keynesian economics requires restraint. Deficits are supposed to be temporary rather than structural. Loose monetary policy is supposed to be temporary, not lingering. Even if we allowed more “pre-heating” of the economy and even if we turned up the heat to boot, there is no reason to think that Democrats would turn off the stove once matters improve.

The markets have not reacted well to the downgrade announcement and politicians have predictably blamed each other. Rep. Bachman, the tea party favorite, called on President Obama to fire Treasury Secretary Geithner. Even after the downgrade, Rep. Cantor joined Speaker Boehner to call on congressional Republicans to resist attempts by President Obama to increase revenue in an effort to reduce the nation’s debt.

Republican presidential candidate and former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney blamed President Obama for the S&P downgrade. “America’s creditworthiness just became the latest casualty in President Obama’s failed record of leadership on the economy,” Mr. Romney said in a statement. Sarah Palin agreed via Facebook.

On the other hand, Sen. John Kerry (D-MA) called the situation a “tea party downgrade,” Former Democratic National Committee Chair Howard Dean claimed that the opposition’s positions were “not founded in reality.” Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley blamed Tea Party “obstructionism.” Massachusetts Rep. Barney Frank said that the downgrade of the U.S. government’s credit rating was the Republicans’ fault.

There is little reason to expect political leaders across the board to come together and reach any kind of serious solution. The credit of the United States is thus impaired accordingly.

CONCLUSION

The major criticisms of S&P and its analysis are largely accurate. S&P’s credibility remains a problem and the $2 trillion calculation mistake was a disgrace. Yet these realities miss the fundamental point. David Beers, global head of sovereign ratings for S&P, told CBS News that the downgrade was a reflection of the increasingly “unpredictable” nature of the debate surrounding U.S. economic decisions. Outgoing S&P President Deven Sharma, in a CNBC interview, pointed out that going from a AAA to AA+ rating “doesn’t mean [the U.S. is] going to default, it just means it’s more risky today than a year ago.” They are surely right about that, and there is very little basis for optimism going forward. ,” As Sharma summarized,. “our job is to tell the investor: This is where we think the risk is.”

Besides, those who wistfully long for the days of non-politically influenced ratings decisions are deceiving themselves. Those days never existed. The dollar’s status as reserve currency and the status of U.S. Treasuries as crisis investment of choice did not come about via fiat from the IMF. They were earned based upon the reasoned judgment of investors – one at a time – with respect to their analysis of all relevant factors, many of which were and are political. A ratings agency that does not consider political risk when evaluating sovereigns is simply not doing its job.

S&P’s action can be seen as a clarion call with respect to the country’s eroding economic strength and global standing. Our need to regain the initiative through better economic policymaking and more coherent governance is clear. But instead of responding to that call, I fear that various political factions will continue to focus on S&P’s alleged lack of credibility, to blame everyone else, and to continue to forego real, substantive and increasingly necessary change. The S&P downgrade was entirely deserved. It may have even been overdue.

[1] For example, Paul Krugman responded to the downgrade as follows:

“[I]t’s hard to think of anyone less qualified to pass judgment on America than the rating agencies. The people who rated subprime-backed securities are now declaring that they are the judges of fiscal policy? Really? …

“This is an outrage — not because America is A-OK, but because these people are in no position to pass judgment.”

Robert Reich, Brad DeLong and Barney Frank (among others) took similar positions.

[2] For example, President Obama responded (full speech here) to the downgrade by maintaining that “No matter what some agency may say, we’ve always been and always will be a triple-A country.” Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner claimed that the “S&P decision to cut U.S. credit rating shows stunning lack of knowledge about basic U.S. fiscal budget math.” The Fed, the FDIC, NCUA, OCC issued a joint statement making it clear that “the risk weights for Treasury securities and other securities issued or guaranteed by the U.S. government, government agencies, and government-sponsored entities will not change.” Gene Sperling, director of the National Economic Council, combined criticisms 1 and 2 by asserting that “the magnitude of [S&P’s] error combined with their willingness to simply change on the spot their lead rationale in the press release once the error was pointed out was breathtaking.” Of course, a former Moody’s official disagrees with S&P too and is consistent with Warren Buffet’s view of the downgrade (note, however, that Buffet’s company owns a substantial stake in Moody’s and has an interest in pushing the Moody’s position vis-à-vis S&P’s).

[3] For example, the OECD has objected to this practice. Similarly, Jeffrey Stibel, Chairman and CEO of Dun & Bradstreet Credibility Corp., writing for the Harvard Business Review, does not dispute S&P’s political analysis, but claims that “that is not the point of a credit ratings agency.”

[4] This language, suggestive as it is of personal finance, is potentially deceptive. In times of emergency (for example, World War II for the U.S.), governments may prudently spend substantially more than they take in to deal with the emergency. My comments here relate to the U.S. government’s consistent and ongoing unwillingness to deal with both debt and deficits and thus “live within its means.”

[5] To be fair, those deficit hawks elected for the first time in 2010 can hardly be painted with the hypocrisy brush, but one can still rightly question their actions. Throughout the debate, House Speaker John Boehner described a debt-ceiling increase as a favor to President Obama: “He gets his increase in the debt limit” in exchange for meeting Republican demands on spending cuts without tax hikes. After the President capitulated, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell boasted that the deal “creates an entirely new template for raising the nation’s debt limit. … Never again will any president from either party be allowed to raise the debt ceiling … without having to engage in the kind of debate we’ve just come through.” Sen. McConnell even chortled that Tea Party loyalists in his party “thought the default issue was a hostage you might take a chance at shooting,” which taught the leadership that “it’s a hostage that’s worth ransoming.”

Every Republican presidential candidate except Jon Huntsman came out against the final debt-ceiling deal. These candidates were, in effect, advising congressional Republicans to let the United States default. From a political standpoint, the Republican strategy was a tremendous success (at least to this point). There is no reason to expect the success of that approach (at least as it relates to perception) will not continue to drive Republican strategy. While the debt ceiling will not be dealt with again before the 2012 election, there is no reason not to expect every budget resolution to become a major (and partisan) budget referendum. The players see it as good politics, but S&P rightly recognizes that this political success comes with some major costs.

Indeed, Republicans are already gearing up to oppose any and all tax increases. No plan which seeks revenue growth (even by closing tax loopholes) will be countenanced. “Over the next several months, there will be tremendous pressure on Congress to prove that S&P’s analysis of the inability of the political parties to bridge our differences is wrong,” House Majority Leader Eric Cantor wrote in a letter addressed to House Republicans. “In short, there will be pressure to compromise on tax increases. We will be told that there is no other way forward. I respectfully disagree,” the Virginia Republican added. House Speaker Boehner echoed Mr. Cantor’s position, noting that “raising taxes is simply the wrong approach.” Sen. Jeff Sessions, (R-AL) called tax hikes “unthinkable.”

Republican presidential candidates also remain committed to intransigence. Rep. Bachman went so far as to label warnings of dire consequences on account of not reaching a debt ceiling deal as a “scare tactic.” Moreover, all six Republicans nominated to the debt ceiling compromise “super committee,” which is supposed to effect additional debt reductions by November 23, have signed a pledge devised by Americans for Tax Reform to forswear all tax increases. These leaders make it plain, from their perspective, that impasse is both necessary and desirable. Some Republicans unabashedly want to starve government to death (more here) and, accordingly, are not concerned that current revenues cannot possibly meet expenses.

[6] Democrats were similarly inclined but from the other side. They have offered precious little in terms of actual debt reduction. Indeed, Democrats in both houses of Congress are essentially united on protecting Social Security and Medicare even though the White House concedes (video of President Obama here) that Medicare reform is necessary from a budget standpoint. As Elizabeth Drew points out, even “liberal-leaning budget analysts agree that the budget is on an ‘unsustainable’ path,” yet Democrats were not really interested in substantive compromise, particularly on entitlements.

House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi was melodramatic in her attacks on the cuts in domestic spending that Republicans attached to the debt measure, minimal though they were. She commented that Democrats were trying “to save life on this planet as we know it.” She even asserted that the deal was probably a “Satan sandwich with Satan fries on the side.” Indeed, Democrats continue to oppose nearly all spending cuts and minimized the need for net reductions throughout the negotiations. Even so, Salon editor Joan Walsh accused the President of selling out “core Democratic principles.” On the other hand, Pelosi promises to “hold true to our values of protecting and strengthening Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security” going forward.

To be fair to the Democrats, there is a reasonable argument to be made that while U.S. debt levels are a major long-term problem, the current economic crisis lies elsewhere. Many economists are focusing on consumer demand, jobs and various ways to stimulate the economy. As summarized by Ryan Avent of The Economist: “American growth dropped to stall speed in the first half of the year, and the government is content to saddle the recovery with substantial fiscal tightening over the next year. Europe is on the brink, and its leaders are on vacation. Falling markets will add to reduced confidence. At this point, the self-fulfilling spiral back into recession is underway.” Accordingly, focusing on debt and deficits *now* (what some wags are calling “deficit attention disorder”) is misguided. However, given the general unwillingness of Democrats to make serious and long-term commitments to fiscal restraint, Republican skepticism about Democrats’ willingness to make such commitments after the crisis is surely understandable.

[7] In late 2002, Vice President Dick Cheney summoned the Bush administration’s economic team to his office to discuss another round of tax cuts to stimulate the economy. Then-Treasury Secretary Paul H. O’Neill pleaded that the government – already running a $158 billion deficit – was careering toward a fiscal crisis (quaint, isn’t it?). But by O’Neill’s account of the meeting, Cheney silenced him by invoking his take on Reagan’s legacy: “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”

[8] “But the real problem is that the global economy is badly overleveraged, and there is no quick escape without a scheme to transfer wealth from creditors to debtors, either through defaults, financial repression, or inflation.”

[9] “Many commentators have argued that fiscal stimulus has largely failed not because it was misguided, but because it was not large enough to fight a ‘Great Recession.’ But, in a ‘Great Contraction,’ problem number one is too much debt. If governments that retain strong credit ratings are to spend scarce resources effectively, the most effective approach is to catalyze debt workouts and reductions.”