Note: I will be attending the terrific Evidence-Based Investing Conference on November 15, 2016 in New York. You should too. There is a new and growing movement in our industry toward so-called evidence-based investing (which has much in common with evidence-based medicine). As Robin Powell puts the problem, “[a]ll too often we base our investment decisions on industry marketing and advertising or on what we read and hear in the media.” Evidence-based investing is the idea that no investment advice should be given unless and until it is adequately supported by good evidence. Thus evidence-based financial advice involves life-long, self-directed learning and faithfully caring for client needs. It requires good information and solutions that are well supported by good research as well as the demonstrated ability of the proffered solutions actually to work in the real world over the long haul (which is why I would prefer to describe this approach as science-based investing, but I digress).

There is a new and growing movement in our industry toward so-called evidence-based investing (which has much in common with evidence-based medicine). As Robin Powell puts the problem, “[a]ll too often we base our investment decisions on industry marketing and advertising or on what we read and hear in the media.” Evidence-based investing is the idea that no investment advice should be given unless and until it is adequately supported by good evidence. Thus evidence-based financial advice involves life-long, self-directed learning and faithfully caring for client needs. It requires good information and solutions that are well supported by good research as well as the demonstrated ability of the proffered solutions actually to work in the real world over the long haul (which is why I would prefer to describe this approach as science-based investing, but I digress).

The obvious response to the question about whether one’s financial advice ought to be evidence-based is, “Duh!” Then again, investors of every sort – those with a good process, a bad process, a questionable process, an iffy process, an ad hoc process, a debatable process, a speculative process, a delusional process, or no process at all – all think that they are evidence-based investors already. They may not describe it that way specifically. But they all tend to think that their process is a good one based upon good reasons. Nothing to see here. Move right along.

Nearly as problematic is the nature of evidence itself. The legal profession has been dealing with what good and relevant evidence is for centuries. According to the Federal Rules of Evidence (Rule 401): “Evidence is relevant if: (a) it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence; and (b) the fact is of consequence in determining the action.” That’s a really low bar, which explains why so much more than merely evidence is implicit within the rubric of evidence-based investing.

And therein lies the problem. Committing to an evidence-based approach is a great start, a necessary start even, to sound investing over the long-term. But it’s not enough…not by a longshot. As philosophers would say, it’s necessary but not sufficient. Most fundamentally, that’s because:

- The evidence almost always cuts in multiple directions;

- We don’t see the evidence clearly; and

- We look for the wrong sorts of evidence.

I’ll examine each of these related issues in turn.

The evidence almost always cuts in multiple directions.

Aaron Sorkin’s critically lambasted series, The Newsroom, lasted for three controversial seasons on HBO. It became what was essentially ground zero for hate-watching. It was fascinating and awful while feigning gravity and implying narrative power. It was impossibly frustrating to watch because Sorkin is so incredibly talented.

Anyway, the first episode of the series famously opened with an homage to Network’s galvanizing “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore” rant (a precursor to Trumpism) wherein television news anchor Will McAvoy (played by Jeff Daniels) sat on a journalism school panel at Northwestern University and humiliated a doe-eyed undergrad about how “America is not the greatest country in the world anymore“ in the elite informing the ignorant manner that so often dominated the overarching narrative of the show. Lots of people (mostly on the political left – which is ironic given how the current presidential election has flipped the traditional script as to who trumpets and who denies American exceptionalism) have pointed this speech out to me as expressing what they think and believe about the United States of America.

Sorkin (via McAvoy) provided a long list of facts to support his claim and his alternative (and stronger) assertion, that “There is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world.” Sorkin’s list was culled pretty much straight out of The World Factbook from the CIA (2010 edition). As he has McAvoy recount, we’re seventh in literacy, 27th in math, 22nd in science, 49th in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality (although this one is deceptive because the list counts down from highest to lowest), third in median household income, fourth in labor force and fourth in exports. He is careful to point out, however, that we do lead the world in incarceration rate, religiosity and defense spending. Sorkin doesn’t mention it, but we’re also “number one“ in obesity, divorce rate, drug usage (legal and illegal), murder, porn, national debt and more.

One can even take issue with Sorkin’s claim that America used to be the greatest country on earth. That argument would likely begin by pointing out that despite our republic’s founding being based upon the idea that “all men are created equal” because “they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” we still bought and sold people as chattel for nearly a century thereafter and women were not so endowed for even longer. And then, after the Civil War provided freedom (or a modicum thereof) to slaves, we still wouldn’t allow blacks to vote just because they were black for another century or more. We also waged genocide on native Americans and enforced immigration laws made up of quotas that allowed 100 times as much legal immigration from northern European nations as from, say, Mexico or Kenya. But I digress (again).

My essential point is that the evidence Sorkin brings to bear about America’s lack of standing is powerful indeed. It suggests that our presumed national arrogance and home-country bias is delusional in the extreme. Still, Sorkin’s primary claim about the lack of American exceptionalism is hardly the slam-dunk he assumes it to be and, contrary to his bold assertion, the evidence supporting the idea that America is the greatest country in the world is also powerful indeed. The United States hosts almost 20 percent of the world’s migrants, making it a vastly more popular destination for migrants than anywhere else on the globe.

Even more importantly, the U.S. is by far the most desirable destination for the 700 million adults in the world who say they would like to migrate to another country permanently if they could. In fact, America is 3.5 times more desirable a destination for potential immigrants than any other country in the world. Aaron Sorkin may not think that America is the greatest country in the world anymore, but people who want to escape where they are overwhelmingly think it is. And aren’t they in the best position to discern and decide which country is in fact the world’s best?

The broader point, meanwhile, is the obvious conclusion that the available evidence doesn’t all point in one direction and, in this instance at least, the best available version of the truth, based upon the best available version of the facts and other evidence is hardly certain and hardly dispositive. The evidence, as is usually the case, is conflicted and won’t interpret itself.

We don’t see the evidence clearly.

When I was in law school, I officiated basketball games to supplement my financial aid package. I had refereed a lot previously, but never so consistently and never semi-professionally. Once I had gotten the basics down (e.g., knowledge and application of the rules, authority, positioning, demeanor, etc.), I was surprised at what I realized was my most consistent weakness and problem as an official: I tended to call what I expected to happen rather than what actually happened. I’m sure it occurred more often than I recognized, but I recognized it far too often for comfort. That I still usually made the right call didn’t mitigate my discomfort – process trumps outcome after all.

When I was in law school, I officiated basketball games to supplement my financial aid package. I had refereed a lot previously, but never so consistently and never semi-professionally. Once I had gotten the basics down (e.g., knowledge and application of the rules, authority, positioning, demeanor, etc.), I was surprised at what I realized was my most consistent weakness and problem as an official: I tended to call what I expected to happen rather than what actually happened. I’m sure it occurred more often than I recognized, but I recognized it far too often for comfort. That I still usually made the right call didn’t mitigate my discomfort – process trumps outcome after all.

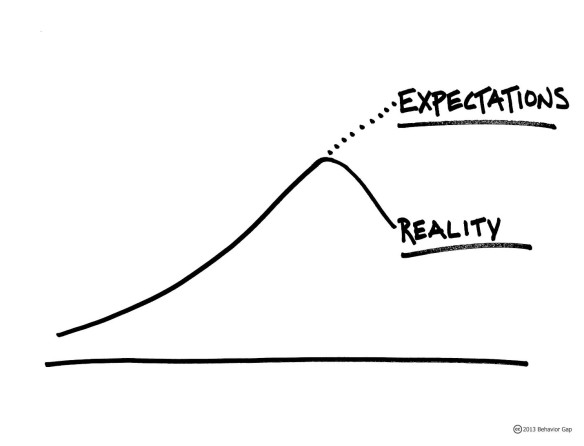

As I saw plays develop, I frequently “knew” what was going to happen based upon lots of previous experience. I knew what to look for. For example, an awkward reach-in leads to a foul. But once in a great while what I expected to happen didn’t actually happen. Still, I whistled what I expected to happen far too often. I had to fight that tendency constantly. My expectations colored my judgment and even (I’m sure, based upon plenty of good research studies) my perception. I “saw” what I expected to see.

By this point, every investment professional and would-be professional has at least a passing knowledge of behavioral finance and its lead actor, confirmation bias, whereby (as it is usually posited) we see what we want to see, accept these desires as truth and act accordingly. I have written about this subject often. Others acting to correct these misperceptions can actually reinforce them, via something called the “backfire effect.” Similarly, attempts to debunk believed myths not based on fact can also reinforce them because they keep repeating the untruth. It seems that people remember the false claim and forget that it’s a lie. And if people feel attacked, especially about something they care deeply about, they resist the facts all the more. Sadly, people will resist abandoning a false belief unless and until they have a compelling alternative explanation – in other words, a better story. We inherently prefer a false model of reality to an incomplete or uncertain but more accurate model.

Confirmation bias comes in three primary flavors. Its standard expression, as noted above, is our tendency to notice and accept that which fits our preconceived notions and beliefs. The current presidential campaign season provides daily examples. We routinely accept or explain away the foibles of candidates we support while jumping all over those of the opposition. My daily Facebook feed is conclusive evidence of this unseemly reality. One person’s depravity and slander is another’s obvious fact. Each side thinks they have chosen the right hero in a fraught morality play with the highest of possible stakes.

But confirmation bias also includes seeing what we expect to see (as with my refereeing example or when we proofread something and read right over an obvious error) and seeing that which is in our interest to see. This last expression is often called “motivated reasoning.” The shocking and famous Simmelweis Reflex is a reflection of this phenomenon and Upton Sinclair offered perhaps its most popular expression: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

As I told Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal back in 2012, “There’s plenty of people who sell bad stuff knowingly, but I think the far bigger problem is inappropriate sales that are well-intended. I’ve seen people who sell bad stuff to their moms, because they thought it was the right thing.” That’s the power of confirmation bias. We come to erroneous conclusions and yet are convinced that they are wholly justified, noble even, based upon our misreading, misunderstanding and misapplication of the available evidence. We simply don’t see the evidence very clearly.

We look for the wrong sorts of evidence.

As humans, we want deductive (definitive) proof, which is rarely available (except in closed systems, like math) but in the real world usually have to settle for inductive (tentative) theories. Unfortunately, induction is the way science works and advances. That’s because science can never fully prove anything. It analyzes the available evidence and, when the force of the evidence is strong enough, it makes tentative conclusions. But these conclusions are always subject to modification or even outright rejection based upon further evidence gathering. The great value of evidence is not so much that it points toward the correct conclusion (even though it often does), but that it allows us the ability to show that some things are conclusively wrong. Never seeing a black swan among a million swans seen does not prove that all swans are white while seeing a single black swan (as in Australia) conclusively demonstrates that all swans are not white.

Thus confirming evidence adds to the inductive case but doesn’t prove anything definitively while disconfirming evidence dispositively demonstrates what is false. Correlation is not causation and all that. Accordingly, disconfirming evidence is immensely (and far more) valuable. It allows us conclusively to eliminate a variety of ideas, approaches or hypotheses. In other words, science progresses not via verification (which can only be inferred) but by falsification (which, if established and itself verified, provides relative certainty only as to what is not true). Thank you, Karl Popper.

That said, we don’t like disconfirming evidence. We tend to neglect the limits of induction and jump to overstated conclusions (especially when they are consistent with what we already think). Few papers get published establishing that something doesn’t work. Instead, we tend to spend the bulk of our time looking (and data-mining) for an approach that seems to work or even for evidence we can use to support our preconceived notions (see above). We should be spending much more of our time focused upon a search for disconfirming evidence for what we think (there are excellent behavioral reasons for doing so too).

As the great Charlie Munger famously said, “If you can get good at destroying your own wrong ideas, that is a great gift.” But we don’t do that, as illustrated by a variation of the Wason selection task. Note that the test subjects were told that each of the cards illustrated below has a letter on one side and a number on the other.

Most people give answer “A” — E and 4 — but that’s wrong. For the posited statement to be true, the E card must have an even number on the other side of it and the 7 card must have a consonant on the other side. It doesn’t matter what’s on the other side of the 4 card. But we turn the 4 card over because we intuitively want confirming evidence. And we don’t think to turn over the 7 card because we tend not to look for disconfirming evidence, even when it would be “proof negative” that a given hypothesis is incorrect. In a variety of test environments, fewer than 10 percent of people get the right answer to this type of question.

I suspect that this cognitive failing is a natural result of our constant search for meaning in an environment where noise is everywhere and signal vanishingly difficult to detect. Randomness is difficult for us to deal with. We are meaning-makers at every level and in nearly every situation. Yet, as I have noted often and as my masthead proclaims, information is cheap while meaning is expensive (and therefore elusive). Accordingly, we tend to short-circuit good process to get to the end result – typically and not so coincidentally the result we wanted all along.

In the investment world, as in science generally, we need to build our investment processes from the ground up, with hypotheses offered only after a careful analysis of all relevant facts and tentatively held only to the extent the evidence allows. Accordingly, we should always to be on the look-out for disconfirming evidence — proof negative — even though doing so is oh so counter-intuitive pretty much all the time. We routinely look for the wrong sorts of evidence.

The root and the fruit of the problem.

The root of this problem is obvious: We’re human. On our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, assertive truth-tellers. However, on most days, most of the time, we’re delusional, lazy, partisan, arrogant confabulators. Evidence is what really matters, but with respect to persuading those we wish to persuade, confidence is at least as important as competence, and emotion matters even more.

Per the great scientist and statesman Francis Bacon (in The Advancement of Learning): “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties.” Traditional economic theory insists that we humans are rational actors making rational decisions amidst uncertainty in order to maximize our marginal utility. Sometimes we even try to believe it. But we aren’t nearly as rational as we tend to assume. We frequently delude ourselves and are readily manipulated – a fact that the advertising industry is all too eager to exploit. As Ben Carlson puts it, “Stories, narratives and a good sales pitch still seem to carry more weight than anything else.” So stories, narratives and a good sales pitch are what we get. That’s the fruit of the problem.

Watch Mad Men‘s Don Draper (Jon Hamm) use the emotional power of words to sell a couple of Kodak executives on himself and his firm while turning what they perceive to be a technological achievement (the “wheel”) into something much richer and more compelling – the “carousel.” Note that evidence doesn’t make the sale.

“It’s not a spaceship. It’s a time machine.”

Those (fictional, of course, but it beautifully makes the point) Kodak guys will hire Draper, of course, yet their decision-making will hardly be rational. Homo economicus is a myth. But, of course, we already knew that. Even young and inexperienced investors can recognize that after just a brief exposure to the real world markets. The “rational man” is as non-existent as the Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot and (perhaps) moderate Republicans. Yet the idea that we’re essentially rational creatures is a very seductive myth, especially as and when we relate the concept to ourselves (few lose money preying on another’s ego). We love to think that we’re rational actors carefully examining and weighing the available evidence in order to reach the best possible conclusions. Oh that it were so.

If we aren’t really careful, we will remain deluded that we see things as they really are. The truth is that we see things the way we really are. I frequently note that investing successfully is very difficult. And so it is. But the reasons why that is so go well beyond the technical aspects of investing, difficult though they are. Sometimes it is retaining honesty, lucidity and simplicity – seeing what is really there – that’s so hard.

We routinely choose ideology over facts, especially when we think it is in our interest to do so. We all develop overarching ideologies as intellectual strategies for categorizing and navigating the world. Psychological research increasingly shows that these ideologies reflect our unconscious goals and motivations rather than anything like independent and unbiased thinking. This reality fits conveniently together with our tendency to prefer stories to data and our susceptibility to the narrative fallacy, our tendency to look backward and construct a story that explains what happened along with what caused it to happen, more consistent with what we already think and expect than with the evidence, especially when the story supports our overall beliefs and interests.

This tendency is so strong that NBC’s chief marketing officer, John Miller, can claim with a straight face that the network uses tape delay for its current coverage of the Olympics because the women who make up the majority of the Olympic audience are invested in narrative over numbers. “They’re less interested in the result and more interested in the journey,” he said. “It’s sort of like the ultimate reality show and miniseries wrapped into one.”

We all like to think that our outlooks and decision-making are rationally based processes — that we examine the evidence and only after careful evaluation come to reasoned conclusions as to what the evidence suggests or shows. But we don’t. Rather, we spend our time searching for that which we can exploit to support our preconceived commitments, which act as a pre-packaged foundation for interpreting the world. We like to think we’re judges of a sort, carefully weighing the alternatives and possibilities before reaching a just and true verdict based entirely upon good evidence. Instead, we’re much more like lawyers, looking for anything – true or not – that we think might help to make our case while also remaining on the look-out for ways to suppress that which hurts it.

In 2006, researchers randomly mixed and labeled news stories from a single, separate news source as coming from four different outlets – Fox, CNN, NPR and the BBC – and showed them to a random sampling of readers. Significantly, the very same news story attracted a substantially different audience depending upon the network label. Thus, for example, conservatives chose to read stories labeled as being from Fox while liberals ignored them, no matter their actual source and content. In other words, the exact same story with the exact same headline was deemed readable or not solely based upon its apparent source. The conclusion is obvious and unsurprising: “people prefer to encounter information that they find supportive or consistent with their existing beliefs.” Therefore, people generally “wall themselves off from topics and opinions that they would prefer to avoid,” irrespective of the evidence.

Perhaps worst of all, because of our bias blindness (not to mention the way we consistently overestimate our abilities and skills), it is extremely difficult for us to see that there might be something wrong with our own analyses, perspectives and processes. Everybody else may be biased and wrong, but we remain convinced that we routinely come to a careful and objective conclusion for ourselves based upon the best available evidence. We have many inherent weaknesses conspiring to inhibit us from making good decisions.

We may not be all that rational, but it’s also a myth to assert or assume that we need to take emotion out of our decision-making process in order to make it better. That myth has a reasonable underpinning – as noted, we inherently prefer words to numbers and narrative to data, often to the immense detriment of our understanding. Per Nate Silver in an interesting interview, “our brains are wired to build stories around essentially random data.” But we don’t need to be like Dr. Spock to make good decisions. In fact, that wouldn’t likely help. Investing like Spock would leave us devoid of phronesis – the subtle, embodied and practical wisdom that comes from combining learning with judgment born of experience, and that which used to be the goal of education in the Renaissance. It would also leave us cold and thus less likely to follow through with our plans.

In a careful study that examined why people misperceived three demonstrable facts used to support very different political positions – that violence in Iraq declined after President George W. Bush’s troop surge; that jobs increased during President Obama’s tenure; and that global temperatures are rising – the research showed two remarkable things. Firstly, people are more likely to accept evidence if it’s presented unemotionally, in graphs. But secondly, they’re even more accepting of it if the factual presentation is accompanied by “affirmation” that asks respondents to recall an experience that made them feel good about themselves.

Consider the Mad Men clip again. Draper uses his depiction of the carousel not to tout its newness and efficiency, but rather to conjure memories that allow us to circle back towards home, security and presumed truth, despite the chaos and uncertainty that seem to overwhelm us. We may even find our perception further blurred by tears. Notice how psychiatrist Steven Schlozman of the Harvard Medical School describes it.

“We remember what we remember not just for the facts but also for the feelings that go along with the facts, and the ability to balance feeling with fact is what keeps us out of trouble. The converse, however, is also true. The inability to balance feelings with facts allows all hell to break loose.”

Unrelated emotions can hurt our ability to make good decisions. But more intense related feelings can actually aid investment decision-making.

Narratives are crucial to how we make sense of reality. They help us to explain, understand and interpret the world around us. They also give us a frame of reference we can use to remember the concepts we take them to represent. As reported in The Atlantic in the context of sports and political analytics, “[d]ata is an incredibly valuable resource for organizations, but you must be able to communicate its value to stakeholders making decisions.” We all recognize that value judgments are often powerfully and dangerously emotional. Thus we need both reason and emotion to make good decisions. Evidence isn’t enough.

As I have noted previously in another context, this idea is consistent with research showing that in order to help people understand the implications of various findings and conclusions – and to change behavior – we often need to do more than lay out an evidence-driven, logical argument. Instead (or, better yet, in addition), we need to provide a sort of emotional charge. Thus, for example, instead of simply showing people the numerical consequences of a certain action, we need to find a way to load the results with aversive emotion. “Load” is obviously a – well – loaded word. But I chose it to emphasize the size of the stakes. Similarly, we can help ourselves think longer-term by actively considering what our future might be like (or even what successful people do in similar situations) and how better planning will make that future better.

In the context Draper created, the carousel seems to sell itself. I have watched this scene many times, and I always feel (more than think) that the “wheel” is not worthy of the talent that sells it. Moreover, the line between being sold and being inspired is blurred to the point of disappearance. Yet utter rationality alone – without emotion to provide a kick to make the experience stick – makes it much harder for us to make tough decisions. For example, notice the power that a fear of regret (“Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life”) provides both Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), forced to choose between “love and virtue” at the conclusion of the brilliant Michael Curtiz film, Casablanca.

Great communicators evoke images and emotions through the use of compelling narrative that can be used to incite a strong response. During the 1984 election campaign, for example, Ronald Reagan talked about our future in outer space and the importance of our going there and conquering the unknown while his soon-to-be-vanquished opponent, Walter Mondale, kept talking about how much doing so was going to cost. It isn’t hard to guess who captured people’s imaginations and won their votes. Better still, watch this address from the 40th anniversary of D-Day and feel the evocative power of Reagan’s words. I dare you not to be stirred.

If we are best to commemorate those who began the rescue of Europe, “the boys of Pointe du Hoc,” like Reagan we won’t focus upon a factual recitation of their amazing accomplishments. Instead, we will inspire images that seem to put things in proper perspective. In the words of the poet Stephen Spender, they are men who in their “lives fought for life and left the vivid air singed with honor.”

Or consider the emotional power of Martin Luther King’s words as he calls on all Americans, indeed, “all God’s children” to aspire to, to work for and to demand his dream – based upon self-evident truths. It’s a bit easier for us today to hope for a world where children will be judged “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” But the heroism of Dr. King and others in fighting for freedom would not and could not have happened without an undergirding of emotional rightness. Mere evidence did not enlighten a generation and transform a nation.

Developing an investment process that can overcome our irrational tendencies and help us stick to its commitments is, quite obviously, extremely difficult. It requires measured rationality and emotional stick-to-it-iveness. It requires the fortitude to act the fool by allowing one’s commitments and beliefs to be challenged consistently and aggressively.

None of us likes to be challenged and corrected. Few of us are willing to accept such an approach even in theory. And most people doing the challenging don’t do it in the right spirit and for the right reasons. But invest in our processes we must if we are to succeed. Our irrationalities will necessarily overwhelm us unless we do everything we can personally so as consistently to check our work and have it challenged by smart and talented people we encourage to “tear it apart.” That’s because we are consistently and dangerously much less rational than we assume. The evidence often doesn’t show what we think it does and is rarely as strong as we routinely assume.

Therefore, evidence is necessary but not sufficient for a good investment process. As described by John Ioannidis of Stanford with respect to medicine: “’evidence-based medicine’ has become a very common term that is misused and abused by eminence-based experts [“I’m right because I’m highly regarded”] and conflicted stakeholders who want to support their views and their products, without caring much about the integrity, transparency, and unbiasedness of science.” Thus clinical evidence can become “an industry advertisement tool.” Similarly, evidence-based investing runs the same risks as evidence-based medicine – poor analysis of the available evidence, jumping from correlation to causation, the trumping of data by stories and ideologies, usurpation of good ideas by commercial interests as well as overstated implications and results.

A good investment process demands good supporting evidence. But there is no substitute for good examination and analysis of the available evidence as well as good interpretations of that evidence to come up with the best possible iteration of the truth. Information (evidence) is cheap. Meaning is expensive. Insight – that’s priceless.

Pingback: Quantitative Value | The Personal Finance Engineer

Simply brilliant.

Thank you, Jeff, and thank you for reading.

Pingback: 08/11/16 – Thursday’s Interest-ing Reads | Compound Interest-ing!

Pingback: Being Process-Oriented Means…

Pingback: News Worth Reading: August 12, 2016 | Eqira

Pingback: Happy Hour: Investor Attributes • Novel Investor

Pingback: Weekend reading: Another early retiree “de-retires” – Frozen Pension

This is a beautiful piece of writing and a fabulous collection of clips to illustrate it – you have made my afternoon with your priceless insight.

Great piece (came here via Monevator site in the UK); thanks for posting. Wd be very interested in another piece addressing other big questions about “Evidence-based investing”, eg the fact that – unlike physics (and to a lesser extent, medicine) – there are no genuine unchanging “fundamental constants”, and how the very identification of an effective strategy can lead to it being undermined pretty rapidly via market efficiency.

In physics (my field, along with EBM) we have it easy: electrons always behave the same. Even in medicine there are certain constants that can be exploited – eg homeostatis. In investing….not so much. One example I’ve always liked is the supposed “law” of anti-correlation between bonds and equities. Nice idea…except the correlation between the US S&P500 market index and long-term US Treasury bonds has switched signs 29 times from 1927 to 2012, and has ranged from –0.93 to +0.84 ( N. Johnson et al., ‘The stock–bond correlation’, PIMCO Quantitative Research Report, November 2013).

Looking forward to hearing more !

Wow, Wow and wow. Great Writeup.

Pingback: The Best Investment Writing 2016 | Meb Faber Research - Stock Market and Investing Blog

Pingback: Top Plays of the Week - Financial Coach Group

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans | Male Health Clinic

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans – Bear News

Pingback: Three Tips for Proof-Based mostly Retirement Plans | CRTYPRO

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans | Market News & Forecast

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans | BIZ solutions

Pingback: Three Tips for Evidence-Based Retirement Plans