In a nutshell…

In a nutshell…

The world is a big and complicated place.

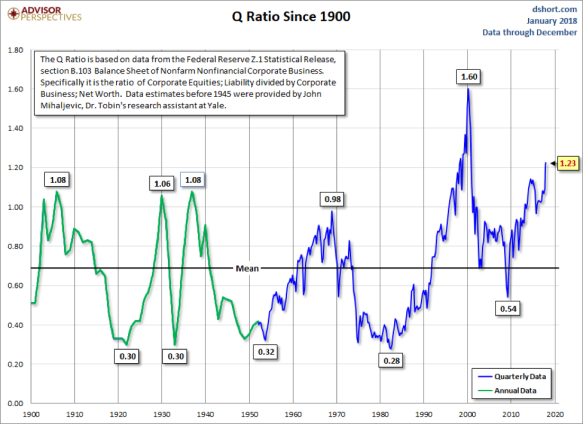

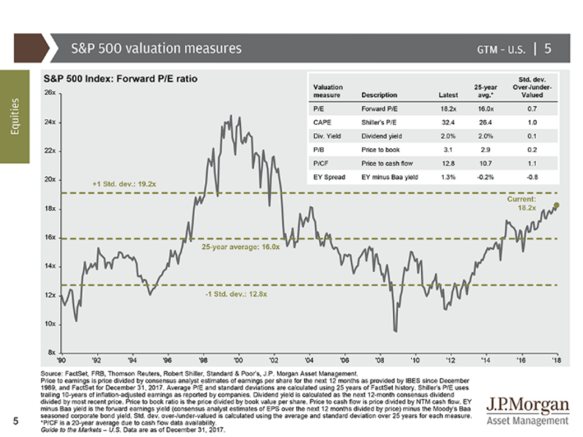

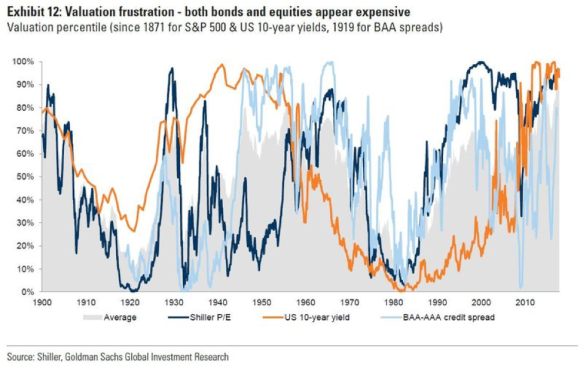

If you want to find reasons why it might collapse, and soon, they are easy to find. We are terribly loss averse, after all, and there is always bad news to report. The stock market goes down on roughly 47 percent of all days. Valuations are high. Bonds are rich too. The rally has been a long one and, in historical terms, we are overdue for a correction.

Worse than that, and more importantly, we could go to war with North Korea (or some other country). The Middle East could explode. We could face a monumental environmental crisis. We could suffer a major terrorist attack. The economy could dramatically underperform or simply run out of steam. We could experience some hitherto unknown problem.

The world is a big and complicated place.

However, the markets and the economy are in pretty good shape. In fact, pretty much the world over, markets and economies are in pretty good shape. There is no obvious impediment to that trend continuing (not that there needs to be for markets to get crushed) and things still seem to be improving.

Moreover, betting against the markets is dangerous business indeed. Over the past 90 years, as Ben Carlson has shown, the S&P 500 has seen 66 calendar-year gains to just 24 losses, making money nearly three out of every four years, with an average annualized return of 9.6 percent and topping 20 percent one-third of the time. In the 66 fat years, the average return was over 20 percent; 51 of those 66 years saw double-digit returns. In the good years, the gain was in the 8-12 percent range only four times.

Although longer-term expected returns are well below trend, largely due to high valuations, I remain constructive on stocks and very constructive on foreign stocks. I am neutral to slightly negative on bonds. Since getting there is at least half the fun, since the details and the rationales are crucial, and since understanding the limitations of this sort of Outlook are imperative, I trust you will stick with me for this, my annual Investment Outlook for 2018.

The Year in Review

Monumental change happens. Up becomes down and down becomes up. True north reverses polarity, quite literally, although it doesn’t happen very often.

Over the past 20 million years, the Earth’s magnetic poles have flipped every several hundred thousand years or so. Accordingly, over much of pre-history, a compass would have indicated that true north was in Antarctica.

Science has not yet ascertained exactly what triggers those reversals, although we do know that the process is gradual and occurs over millennia. Since the last major pole reversal happened roughly 780,000 years ago, we are well overdue for another one. For now, Earth’s north magnetic pole is creeping (geographically) northward by about 40 miles a year.

More broadly, human change of any sort also tends to creep along incrementally, without disclosing if, when, where or how a major flip in polarity might happen. We expect them far more often than they occur.

Even so, the changes we saw last year seem, somehow, a lot more major than normal, perhaps even paradigm-shifting. The markets saw tremendous strength in 2017. That strength was coupled with an obvious and historical lack of market volatility. But nothing else felt very calm or orderly. The world overall seems (despite evidence to the contrary) to have more volatility, uncertainty and complexity, not to mention stupidity and evil – in terms of geopolitics, national security, economics, and more – than it used to. William Butler Yeats provided an apt description 99 years ago.

Perhaps President Trump is ushering in a political polarity shift. Perhaps some other monumental change is underway. That said, as Harvard’s Larry Summers argues, we tend to think that the present moment is more dangerous than others, and overstate the risks accordingly. Then again, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.”

Oft-times it seems as though we live in a Dickensian world where it is both the best and the worst of times, with the appropriate categorization predicated upon one’s politics. After the recent passage of his tax bill, President Trump was quick to proclaim that he is, as promised, “making America great again.” If you’re not on the Trump Train, as late-night talk show host Jimmy Kimmel put it, most of the time “it feels like someone has opened a window into hell.”

Meanwhile, the stock market continues to rally. University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler, who won a Nobel Prize in 2017, summed things up nicely: “We seem to be living in the riskiest moment of our lives, and yet the stock market seems to be napping: I admit to not understanding it.”

As the late comedian George Carlin explained, “You are given a ticket to the freak show. When you’re born in America, you are given a front row seat, and some of us get to sit there with notebooks. And I’m a notebook kinda guy.”

I’m not the creative engine that Carlin was (obviously). And I’m surely no comedian. But I am “a notebook kinda guy.” So let me empty mine out for you to have a look back at 2017 and to look forward to 2018 in order to try to add a bit to our understanding of the markets, the economy and the world. I trust you will enjoy the ride.

The World

It isn’t a reflection of home country bias to state the obvious: President Donald J. Trump was the world’s biggest news story in 2017. More on that shortly. But there were other big stories too.

Three years after the leader of ISIS declared a caliphate, an international coalition largely took back control of territory in Iraq and Syria where the group had imposed draconian rules on the local population. That is an enormous and underreported success. Throughout 2017, however, ISIS propaganda inspired terror attacks in Europe, the U.S., Africa and the Middle East. Militant groups across the world – from Somalia and North Africa to Afghanistan and the Philippines, have pledged allegiance to the group and continue to carry out attacks. So do “lone wolves” in Western democracies.

While the world was looking ahead to February’s Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, North Korea’s provocations continued throughout 2017. North Korea test-fired numerous missiles during the year. Its latest ICBM flew for 50 minutes and reached 2,800 miles in height in late November – a milestone that could threaten the mainland United States if the North masters the technology to top it with a nuclear warhead.

War between North Korea and the United States is a constant threat but a war of words is well underway. President Trump threatened that North Korea will “be met with fire, fury, and frankly power,” and taunted North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un by calling him “Little Rocket Man.” Despite the warnings, Kim responded by calling Mr. Trump “a mentally deranged American dotard” and closed out 2017, in his annual speech for the New Year, by declaring that North Korea is a nuclear power and warning that he was willing and able to attack the U.S. with nuclear weapons. Even so, whether Mr. Trump’s bombastic efforts to convey strength were a factor or not, the North Korean dictator – finally, and in that same speech – expressed a willingness to come to the bargaining table.

The situation in the Middle East is odd even by Middle Eastern standards. Soon after President Trump got the red-carpet treatment in Saudi Arabia, King Salman arrested 11 Saudi princes, while eight highly ranked officials were reported as having died in a helicopter crash. The princes, among others, were shaken down for an estimated $800 billion in assets. Missiles started sailing over the kingdom and were soon blamed on Iran. The prime minister of Lebanon resigned out of fear of assassination. Qatar was hit by an embargo cutting off an estimated 40 percent of its food supply while the country was already embroiled in a serious cash crunch. And don’t forget that pretty much everybody else in the Middle East, including prominent Arab allies, unequivocally hates and is committed to the destruction of America’s best and most important ally there: Israel.

Beginning in April, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested the government of President Nicolas Maduro in demonstrations that became a daily occurrence. Despite huge oil reserves, Venezuela faces food shortages and a broad economic crisis. Following a highly-contentious referendum that produced horrific violence against voters, the Catalonia region of Spain declared itself independent, only for the Spanish government to veto that action. And what began as a smattering of protests in early December over the cost of eggs quickly erupted into a countrywide movement in Iran. Citizens took to the streets in nearly every province, calling for an end to corruption, a better economy, a less-oppressive government and even regime change.

Over 250 million people were estimated to be migrants in 2017. Some of that movement was simply about people looking to improve their lives. But much of the displacement was involuntary. Reports from all corners of the globe revealed horrific stories of people – mostly women and children – fleeing war, unimaginable atrocities and natural disasters. For example, ethnic cleansing in Burma, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Ki, has sent 655,000 people across the border to Bangladesh since August, over half of whom are believed to be children. And in Yemen, where the U.S.-backed Saudi Arabian military routinely destroys homes and villages, over 2 million people are currently displaced.

2017 was a great year for Chinese President Xi Jinping. He began it standing before the world’s economic elite at the Davos forum to give a full-throated defense of globalization and ended it enshrined in the charter of the Chinese Communist Party, officially making him the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao. Meanwhile, China has stepped into the world leadership void created by Mr. Trump’s insistence on “America First” by actively defending both the Paris climate accord and international trade. Consistent with trying to exert leadership, China, the world’s top polluter, announced an ambitious plan to curb its carbon emissions in December.

Natural disasters and extreme weather made perhaps the biggest headlines throughout 2017. Hurricanes, torrential monsoon rains, wildfires and historic flooding broke records for impact as they claimed lives and destroyed property in the Caribbean, South Asia, the United States, and elsewhere. For example, in Sierra Leone and Colombia, hundreds died in mudslides after heavy rains. The United States suffered three devastating hurricanes in short order as well as multiple enormous wildfires. Mexico was hit by two huge earthquakes in September that killed hundreds. There are around four-times as many natural disasters (when 10 or more people are killed or 100 or more affected) today than there were in the 1960s.

The world stage did not experience a low volatility year.

USA

In January, Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th president of the United States following his impressive election upset of Hillary Clinton. As Walter Russell Mead noted in Foreign Affairs, Mr. Trump, seemingly alone, sensed “that the truly surging force in American politics wasn’t Jeffersonian minimalism. It was Jacksonian populist nationalism.”

In response, women in cities across the United States and in 30 countries around the world marched the day after Mr. Trump’s inauguration in support of women’s rights and in defense of freedom of the press. More than one million marched in Washington, D.C. alone. Many were specifically protesting against the President.

President Trump began his administration by insisting his crowd size was the biggest and ended the year insisting that he had signed more legislation than any other president. Both of those claims were clearly and obviously false (the President has a fraught relationship with the truth). But in between – despite a relentless media narrative to the contrary (and only one notable legislative success) – the Trump administration could legitimately claim a significant number of victories. Perhaps most importantly, the President got many more and more types of people involved in politics – for and against him. That is a very good thing.

It is also very good that that, as noted above, the Islamic State’s physical caliphate is all but gone, ISIS is on the run and, following tough new sanctions the Administration got approved by the U.N., Kim Jong Un finally expressed his willingness to come to the bargaining table. When Syria again used a toxic nerve agent on innocents, the President didn’t dither and responded assertively. Despite Mr. Trump’s consistent eagerness to have a good relationship with Vladimir Putin, the Trump administration approved a $47 million arms package for Ukraine, sent troops to Poland’s border with Russia and imposed new sanctions on Moscow for violating the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. After many years of allied recalcitrance, President Trump convinced other NATO members to provide $12 billion more toward collective security.

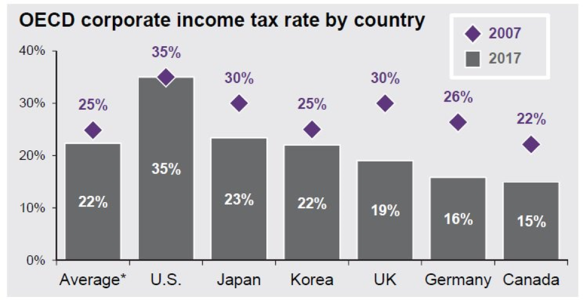

With his appointment and the Senate’s confirmation of Neil Gorsuch, Mr. Trump secured an apparent conservative majority on the Supreme Court, and he is moving at a record pace to fill the federal appeals courts. Finally, the President signed the first comprehensive tax reform in three decades, making domestic corporate tax rates competitive globally (a goal that President Obama proposed but could not accomplish) and providing tax relief for over 90 percent of the middle class.

To be sure, not all the Trump-related news was good. He suffered multiple legislative defeats, most prominently over healthcare. The President controversially fired FBI Director James Comey in early May. Soon thereafter, former FBI Director Robert Mueller was named as special counsel to conduct the investigation into Russia’s attempts to meddle in the 2016 presidential election. To date, the ongoing Mueller investigation has produced four indictments and two guilty pleas, most prominently the plea of former national Security Advisor Michael Flynn. The administration has had enormous trouble filling positions and has suffered huge turnover, from Chief of Staff Reince Priebus on down.

Since the President has consistently claimed not to have many fixed beliefs – everything is deemed negotiable – his foreign policy may well lurch from one position to another as his positions evolve. Indicative of his flexible approach, Mr. Trump has spoken very well of autocrats but has been quick to criticize allies. He has developed a “great relationship” with Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, hosted Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi, exchanged friendly phone calls with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, bragged about his “great chemistry” with Chinese President Xi Jinping and even expressed admiration for the North Korean dictator despite his “little rocket man” vitriol.

Meanwhile, Mr. Trump has attacked U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May and called London Mayor Sadiq Khan “pathetic.” He has strained relations with Australia and Germany, sharply criticized Canada’s trade policies, and antagonized Mexico. Most recently, when the President presented his new national security strategy on December 18, he emphasized his “America First” doctrine and called out his “wealthy allies” for not paying off debts. As Germany’s foreign minister put it, “even after Trump leaves the White House, relations with the U.S. will never be the same.”

An August white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, erupted into violence leaving a young woman dead. Following the incident, President Trump was criticized for being slow to condemn the rally and for suggesting a false equivalence between the Neo-Nazis and counter-protestors.

Despite what cable news might suggest, however, not all important news was about or even related to the President. Mass shootings keep happening with no substantive responses on offer. College campuses provide a constant stream of the bizarre (“They want a campus where everybody looks different but thinks alike”). Irrespective of alleged collusion, insidious Russian efforts to undermine U.S. elections were brought to light and confirmed as true. Following seemingly endless sexual misconduct allegations against high profile men in entertainment, more and more women came forward to expose harassment and assault in politics, business, and elsewhere, damaging and even ending the careers of many. And Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who is considering a run for public office, decided he was no longer an atheist.

2017 was the costliest year ever (by a lot) for weather and climate disasters in the United States, totaling $306 billion, compared with the previous record year, 2005, which saw $215 billion in disaster damage. In late summer, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria hit Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, respectively, over a 26-day period, bringing record winds and water. Harvey flooded most of Houston and is on track to be the costliest storm in U.S. history. Irma, with 130 mph winds, tore through Florida and Georgia before dissipating. As 2018 opens, parts of Puerto Rico are still without electric power due to Maria. Meanwhile, raging wildfires in the west burned more than 1.2 million acres. The Thomas fire became the worst wildfire in California history, destroying over 230,000 acres and 1,000 structures. Northern California’s Tubbs fire charred “only” 36,000 acres in the state’s wine country, but destroyed 5,643 structures and claimed 22 lives in Sonoma and Napa counties.

There was little on the national scene in 2017 that was quiet or calm, either.

The Economy

Despite domestic challenges and a rapidly evolving global landscape, the U.S. economy remains the largest and most important in the world, representing about 20 percent of total global output. In 2017, the U.S. economy advanced from strength to strength with a consistent efficiency. In fact, economic growth picked up markedly as gross domestic product in the third quarter grew at a 3.3 percent annualized rate, its fastest level since 2014, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. There is little inflation or deflation.

American consumers matched that strength with optimism, as consumer confidence was the highest it has been since December 2000. Unemployment is at a 17-year low. Still, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen admits that many jobs are part-time and that their holders would prefer full-time work. Moreover, much of the job growth has been in the retail and food service industries, which don’t pay very well.

In December of 2016, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates for just the second time in ten years. That action was shown to be part of a trend in 2017 as the Fed raised rates three more times, with further tightening likely. The Fed also began the process of reducing its balance sheet, which ballooned on account of quantitative easing to maintain low interest rates in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis.

On the policy front, House and Senate Republicans approved a tax reform plan on December 20, giving President Trump his first major legislative achievement when he signed it shortly thereafter. Despite already-existing robust growth, these deficit-financed tax cuts should lift consumer spending and business investment at least a bit more in 2018, although many analysts doubt that the effect will be long-lived and fear that the long-term impact will be detrimental.

One key question about the tax bill is whether companies will use their windfall to share the winnings with employees and expand their businesses. Immediately after Congress passed the tax legislation, AT&T and Comcast unveiled plans to give all employees a $1,000 bonus. Wells Fargo, one of the bigger expected winners from the tax plan, announced an 11 percent boost to its minimum wage. The question is an important one because wage growth has been disappointing for years, leaving many Americans feeling left out of the recovery and helping to lift the country’s wealth inequality gap to record levels.

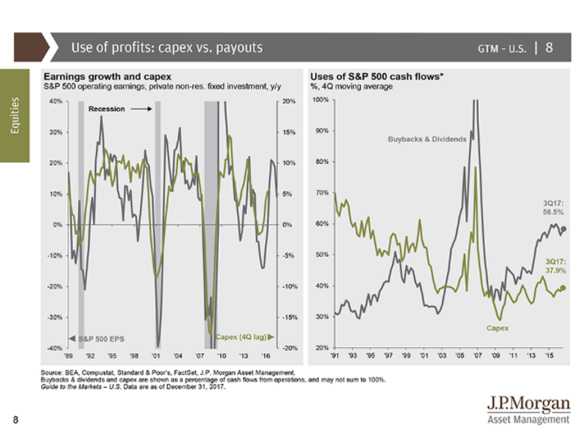

It was a good year for most individual companies in 2017, fueled by this resurgent economic growth at home and abroad. S&P 500 earnings per share are projected to have jumped by a whopping 9.5 percent in 2017, according to FactSet, the fastest pace since 2011. Even better, S&P 500 companies are expected to have brought in record profits in 2017 (once all the data is in), according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. For the first time in three years, the U.S. economy grew at a 3 percent annual rate for back-to-back quarters. Confidence among consumers and businesses is roaring. Non-financial U.S. companies are sitting on an estimated $1.9 trillion in cash, more than doubling their 2008 totals, according to Moody’s.

All is not perfect – far from it. Overall, the U.S. economy added 171,000 new jobs a month in 2017, down from 187,000 in 2016 and 226,000 a month in 2017, and just 148,000 workers in December. The employment rate for workers between the ages of 25 and 54 is still a good deal below its pre-recession peak. Average hourly earnings for all workers rose 2.5 percent in 2017, compared to almost 2.9 percent in 2016, and most of that was eaten up by inflation (benign though it is).

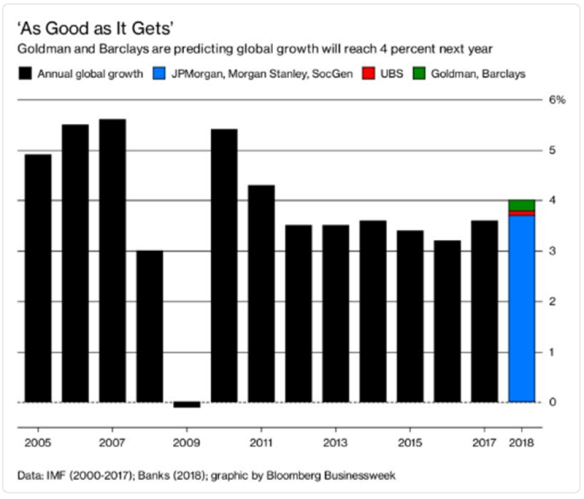

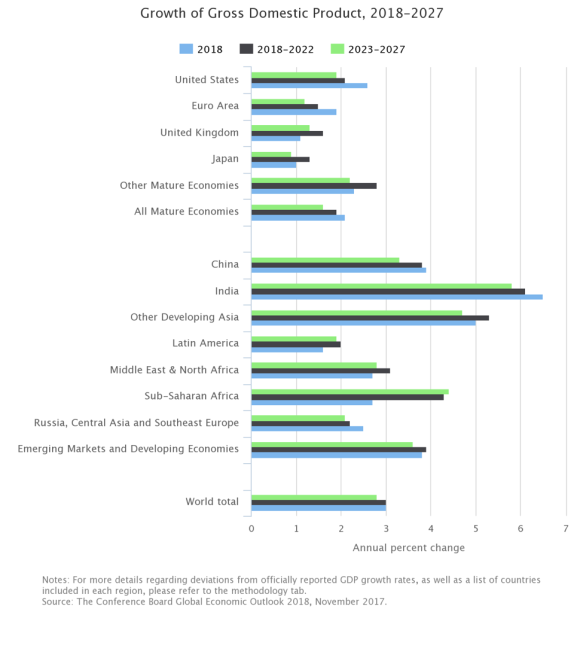

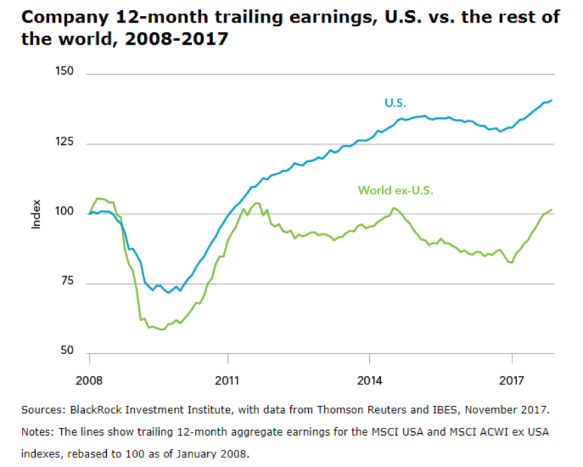

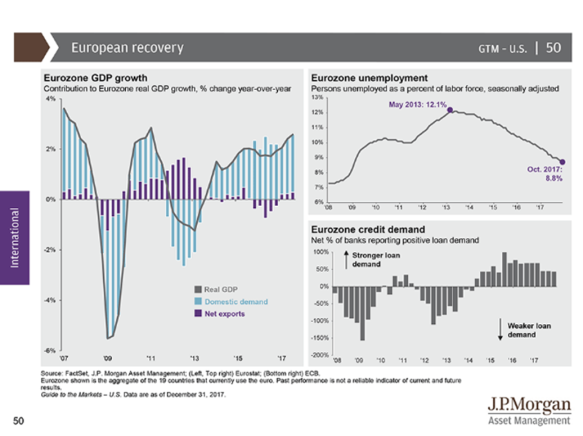

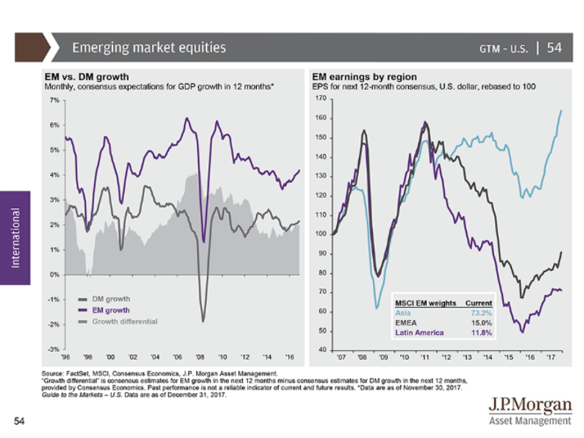

The economy was on very good footing in the U.S., but economic strength was even better abroad. S&P 500 companies that generate most of their sales outside the U.S. grew earnings twice as fast as those focused domestically, according to FactSet. “During 2017, the global synchronized recovery turned into a global synchronized boom that is likely to continue in 2018,” according to Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research.

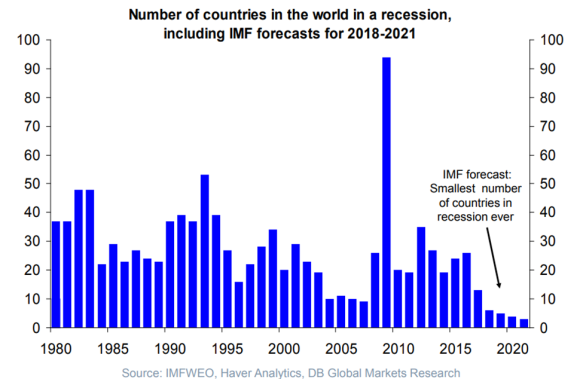

On a global scale, all 45 OECD countries grew together in 2017 for the first time in a decade.

Most parts of the world are exhibiting solid growth, the dispersion in economic performance is remarkably low, and inflationary pressures are muted, consistent with Federal Reserve research which concluded that low economic volatility would become the norm, although punctuated by periods of high volatility. For now, at least, the U.S. economy is in excellent shape and the world economy is about as good as it gets.

It could all change quickly, of course, but the world’s economies are generally humming along smoothly right now. Still, according to Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, “We all need a lot of humility, and especially about the economy.”

The Markets

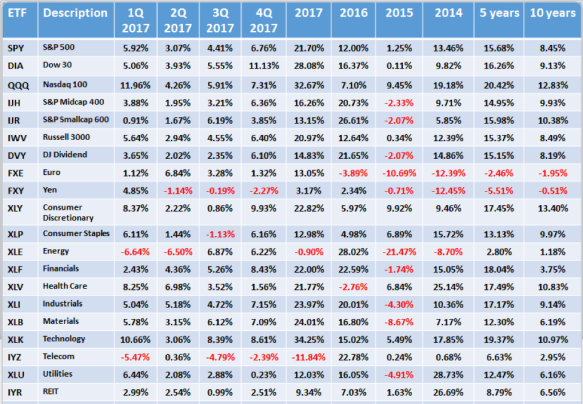

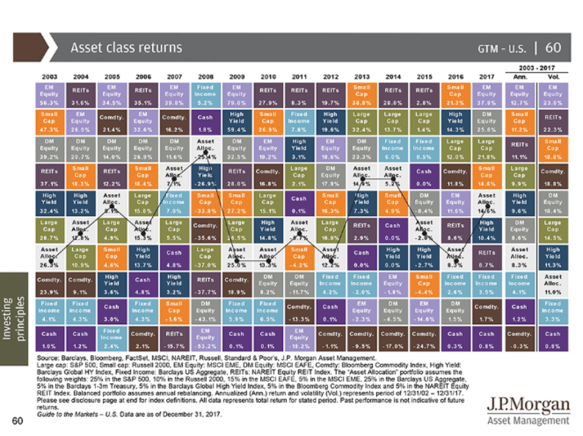

Domestic stocks had a great year in 2017. The concentrated Dow Jones Industrial Average raced 25 percent higher and hit 71 record highs, breezing through milestones and making last year its best since 2013. That the dollar was down roughly 10 percent last year makes the real rise in share prices a little less impressive than it may appear, but the growth in economic strength and consumer confidence are impossible to ignore.

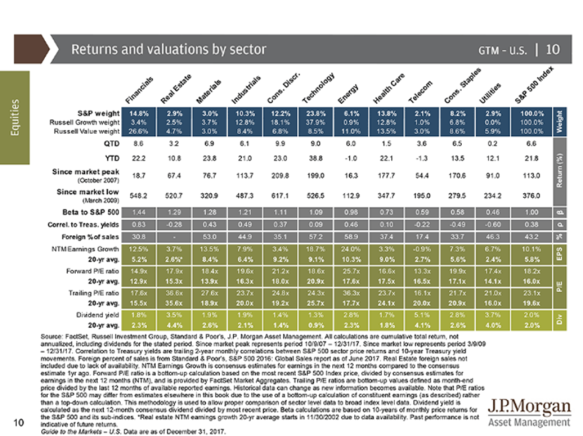

The S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite indices also had their best years since 2013. The broader S&P 500 returned nearly 22.5 percent and posted 62 record highs while the tech-heavy Nasdaq jumped an impressive 28 percent. The small-cap Russell 2000 lagged its larger-cap counterparts, but still earned 13 percent. Growth crushed value, but both did well (+25 percent for S&P 500 Growth; +15 percent for S&P 500 Value). Indeed, it was hard to lose money in 2017 as, according to Morningstar, 95 percent of all mutual funds turned in positive performances, even if they didn’t beat the market.

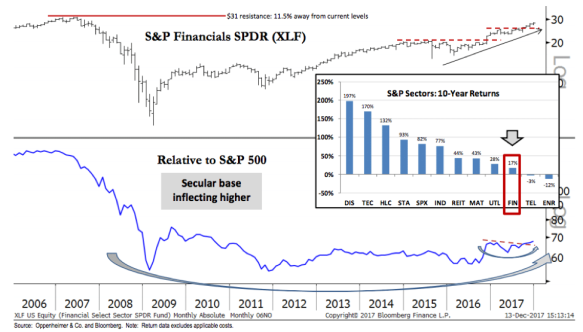

In a world going fully digital in a hurry, with robots, the blockchain, smart phones, the cloud, big data and artificial intelligence spreading throughout homes and businesses, tech stocks topped the 2017 performance charts, led by well-known names like Amazon (+56 percent), Apple (+46 percent), Facebook (+46 percent), Google-parent Alphabet (+33 percent), and Netflix (+55 percent). The S&P 500’s information technology industry group rose 37 percent, putting it at the top of the major groups tracked by S&P Dow Jones Indices. Nine of the 11 sectors of the S&P 500 notched double-digit gains in 2017. The worst-performing sectors were telecom and energy, which each finished the year in the red with small losses.

Wall Street’s stellar 2017 was unusual in that it lacked the type of sharp retreats that usually accompany major rallies. The S&P 500 hasn’t suffered a meaningful pullback since prior to the 2016 election, and volatility metrics have plummeted to record lows. The VIX, a measure of how much volatility traders expect in stocks, ended the year down more than 25 percent. There were only eight days in 2017 that the S&P 500 moved more than 1 percent in either direction – the tamest trading year since 1964, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. The biggest single-day market drop was less than 2 percent.

As ever, there was volatility among individual stocks. Align Technology, a dental tech company, best known for Invisalign, a clear aligner for teeth that is an alternative to traditional dental braces, was the top performing S&P 500 stock, jumping 131 percent in 2017. The worst performer was Range Resources, a Texas-based energy company, which lost half its value.

The booming U.S. stock market is largely the result of resurgent economic growth and blockbuster corporate profits. The U.S. lagged most of the rest of the world in economic growth early in the year, but caught up by summer and delivered annualized GDP growth of 3.1 percent in the second quarter and a 3.3 percent gain in the third, its fastest rate in three years. As noted, S&P 500 sales and earnings rose 6.2 percent and 9.6 percent, respectively, in 2017, according to FactSet.

The biggest market catalyst was likely the long-awaited corporate tax reform and personal tax cuts President Trump recently signed into law. Crucially, the new law provides incentives that encourage companies to return foreign profits held overseas to the U.S. Republicans – who control the White House and both legislative chambers and who passed the tax bill with no Democratic support – are banking on the hope that companies will repatriate some of that cash to create jobs with new spending on equipment and factories. However, if a big chunk of the money goes towards share buybacks and paying down debt, as many expect, those moves should still further juice stock prices.

Those who missed out on the bull market may wonder if it’s too late to get in now. Yet most market strategists are predicting more gains in 2018, especially as the impact of the tax overhaul is felt. If the tax plan creates the kind of growth President Trump has promised, the market could have a lot more room to run. However, Moody’s recently estimated the tax law will only add 0.1 or 0.2 percentage points to 2018 GDP growth. Others anticipate a bit more stimulus, in the range of 0.6 percent.

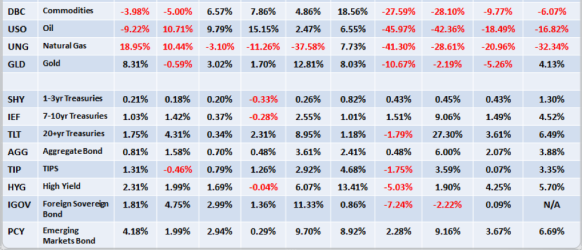

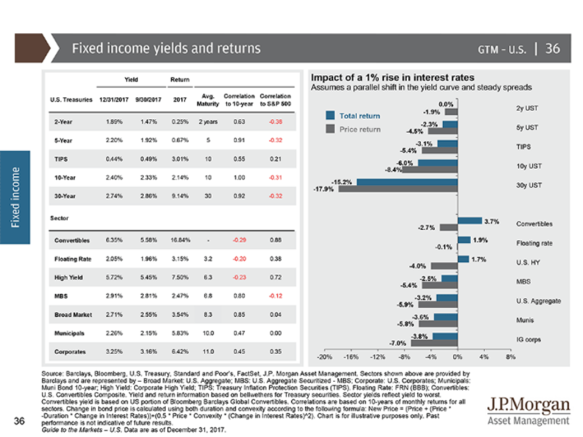

In the fixed income markets, the yield curve flattened dramatically in 2017. The short end of the curve saw interest rates rise roughly 40bp as the Fed continued its program of raising short-term rates with its third rate increase of the year and the fifth this cycle in December. Meanwhile, the 30-year U.S. Treasury bond actually rallied about 10bp to yield roughly 2.75 percent. The spread between 2-year and 30-year U.S. Treasury paper reached a 10-year low in December, when a buyer of U.S. Treasuries could only pick up an additional 85bp of yield for extending 28 additional years out the curve.

The Summary of Economic Projections “dot plot” continues to suggest three more rate hikes in 2018 and another two in 2019. Economic growth has remained strong, with two consecutive quarters of above-trend, three percent annualized GDP advances (as noted above). The Fed has also revised its labor market outlook from “some further strengthening” to “strong,” as the unemployment rate approaches historic lows at 4.1 percent. The more hawkish tone of the Fed’s most recent statement points to positive near-term economic growth and continued strong equity markets, which help to explain why credit spreads are historically tight.

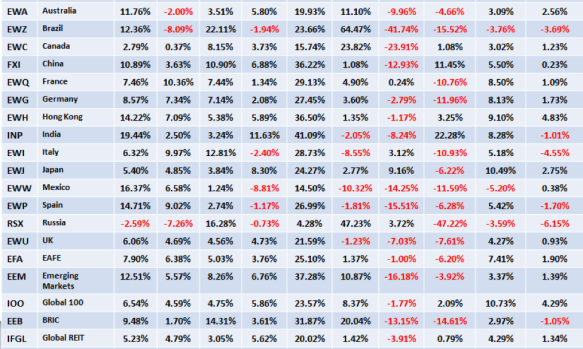

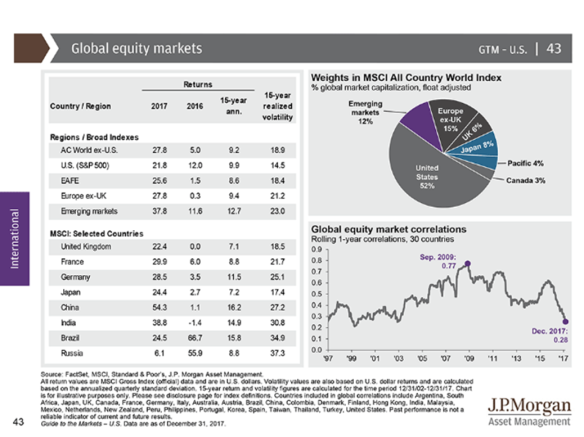

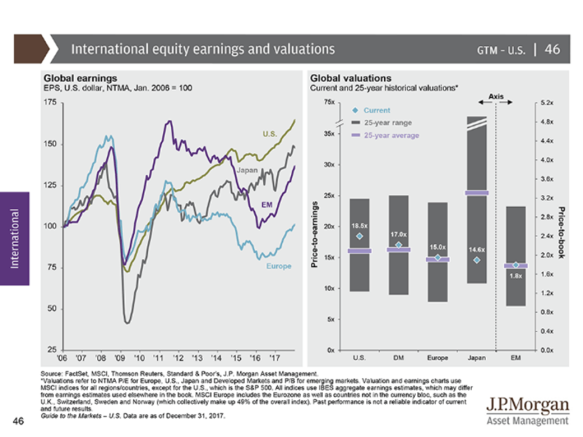

As great as domestic equity returns have been, they were actually below average in 2017 on a worldwide basis. Global stock markets ended 2017 strongly and all but nine of the 73 major international indices closed 2017 in positive territory in their local currency, largely due to a strong worldwide economy and central banks’ go-slow approach to easing financial support. The MSCI all-country world index gained 22 percent or $9 trillion on the year to close at an all-time high.

2017 was a year when easy monetary policy and budding global growth came together to deliver blockbuster returns for the world’s emerging markets. The major emerging markets indices did even better, returning more than 35 percent. Currencies and stocks in developing economies provided their biggest rallies in eight years as even many of the riskiest markets shrugged off various crises and threats to deliver gains for investors. EM bonds also had a good run, with local-currency emerging-market debt providing their best returns since 2012 amid the loose money policy environment.

Eurozone confidence is at a 17-year high.

The U.K.’s FTSE 100 returned a relatively modest 7.6 percent in 2017, but closed the year at an all-time record level. France gained 9 percent, Germany’s DAX earned 13 percent while Italy and Spain all significantly outperformed the U.S. and Turkey rallied 48 percent.

Outside of Europe, Brazil beat the U.S. and Nigerian stocks surged 42 percent. Argentina’s Merval index gained 77 percent last year and hit a record high in the final week of 2017.

In Asia, Japan’s Nikkei 225 jumped 19 percent. Although China’s major mainland indexes in Shanghai and Shenzhen struggled, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng charged ahead by 36 percent. In India, over 80 stocks on the BSE 500 more than doubled investors’ wealth during 2017, even as the BSE 500 rallied 35 percent. Two Indian stocks – HEG and Indiabulls Ventures – delivered over 1,000 percent returns during the year. Qatar’s stock market was the big foreign loser, tumbling 18 percent amid a spat with its neighbors: Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

Stock markets in the United States had a great year in 2017. Global stock markets did even better.

What’s Next?

Aaron Sorkin’s critically lambasted series, The Newsroom, lasted for three controversial seasons on HBO. It became what was essentially ground zero for hate-watching. It was fascinating and awful while feigning gravity and implying narrative power. It was impossibly frustrating to watch because Sorkin and the cast are so incredibly talented.

The first episode of the series famously opened with an homage to Network’s galvanizing “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore” rant (a precursor to Trumpism), wherein television news anchor Will McAvoy (played by Jeff Daniels) sat on a journalism school panel at Northwestern University and humiliated a doe-eyed undergrad about how “America is not the greatest country in the world anymore” in the elite informing the ignorant manner that so often dominated the show’s overarching narrative.

Sorkin (via McAvoy) provided a long list of factoids to support his claim and his alternative (stronger) assertion, that “There is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world.” Sorkin’s list was culled pretty much straight out of The World Factbook from the CIA (2010 edition). As he has McAvoy recount, we’re seventh in literacy, 27th in math, 22nd in science, 49th in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality (although this one is deceptive because the list counts down from highest to lowest), third in median household income, fourth in labor force and fourth in exports. He is careful to point out, however, that we do lead the world in incarceration rate, religiosity and defense spending. Sorkin doesn’t mention it, but we’re also “number one” in obesity, divorce rate, drug usage (legal and illegal), murder, porn, national debt and more.

Some would take issue with Sorkin’s claim that America used to be the greatest country on earth. That argument would likely begin by pointing out that despite our republic’s founding being based upon the idea that “all men are created equal” because “they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” we still bought and sold people as chattel for nearly a century thereafter and women were not so endowed until much later. Then, after the Civil War provided freedom (or a modicum thereof) to slaves, we frequently wouldn’t allow blacks to vote just because they were black for another century or more.

The evidence Sorkin brings to bear about America’s lack of standing is powerful. It suggests that our presumed national arrogance and home-country bias is misplaced. Still, Sorkin’s primary claim about the lack of American exceptionalism is hardly the slam-dunk he assumes it to be and, contrary to his bold assertion, the evidence supporting the idea that America is the greatest country in the world is also powerful.

The United States hosts almost 20 percent of the world’s migrants, making it a vastly more popular destination for migrants than anywhere else on the planet. Even more importantly, the U.S. is by far the most desirable destination for the 700 million adults in the world who say they would like to migrate to another country permanently if they could. In fact, America is 3.5 times more desirable a destination for potential immigrants than any other country in the world. Aaron Sorkin may not think that America is the greatest country in the world anymore, but people who want to escape where they are overwhelmingly think it is. And aren’t they in the best position to discern and decide which country is the world’s greatest?

The broader point, meanwhile, is that the available evidence rarely points in only one direction and, in this instance at least, the best available version of the truth, based upon the best available version of the facts and other evidence is hardly certain and hardly dispositive. The evidence, as is usually the case, is conflicted and won’t interpret itself. To pick a simple example, according to the Urban Dictionary, idk stands for “I don’t know.” However, on its face, there is no reason not to think that it stands for “I do know,” the exact opposite. And, one more thing: we aren’t very good at evaluating evidence, conflicted or otherwise, as we shall see shortly.

With this crucial caveat in mind, and following a crucial reminder about the limits of forecasts, let’s begin to sift the available evidence to see what we can discern about the markets going forward.

Forecasting Follies

Nokia was not the first company to release a commercially viable mobile phone, but it was the first to do it well, with true mass appeal. The seemingly rhetorical question asked by Forbes on the 2007 cover reproduced here (at right) turned out to be a very good one, the answer to which was, “Yes – Apple.”

Nokia was not the first company to release a commercially viable mobile phone, but it was the first to do it well, with true mass appeal. The seemingly rhetorical question asked by Forbes on the 2007 cover reproduced here (at right) turned out to be a very good one, the answer to which was, “Yes – Apple.”

Nokia’s smartphone market share in 2007 was a dominant 49.4 percent. However, Nokia was already in trouble. The Finnish giant simply didn’t know it yet. On January 9 of that year, Steve Jobs had pulled an iPhone out of his pocket, introduced it to the world, and changed the mobile phone industry forever. In 2008, Nokia’s market share fell to 43.7 percent, then to 41.1 percent in 2009 and 34.2 percent in 2010. By 2013, when its phone business was purchased by Microsoft, it had fallen to a paltry 3 percent. A $10,000 investment in Nokia ten years ago, when it was the clear leader in the mobile phone market and the Forbes cover came out, would be worth less than $3,500 today.

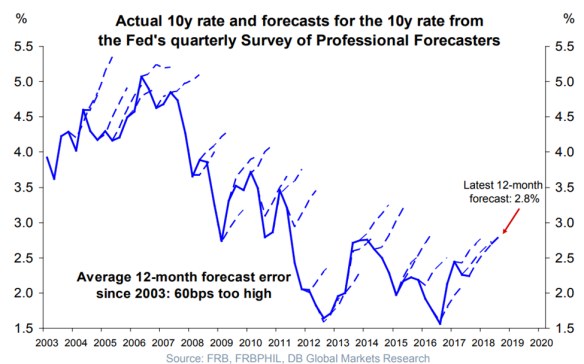

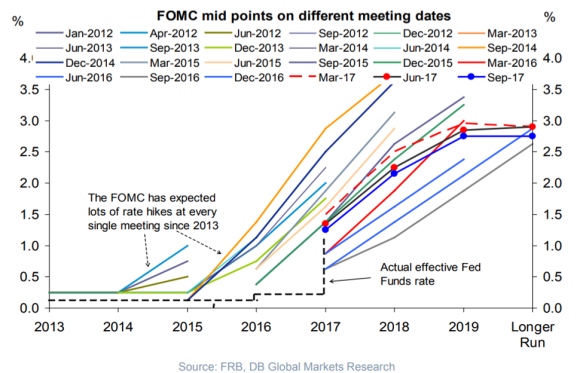

Forbes is hardly alone. Indeed, the list of horrible market calls by alleged experts is an exceedingly long one. The Fed surveys professional forecasters about interest rates every quarter with spectacularly poor results.

Of course, the Fed itself is no better.

Such failures are absolutely normal. The median “expert” forecast of annual S&P 500 returns is only rarely remotely close to the actual result (and that is almost surely accidental). More than half the time since 2000 the miss has been either too high or too low by an amount bigger than the S&P’s nine percent average annual gain. Similarly, U.S. Treasury yields have been expected to rise every year for the past decade, according to forecasts collected by Consensus Economics, yet they have gone down more often than not. Even when yields went up, the moves were close to the predicted levels only once, back in 2009.

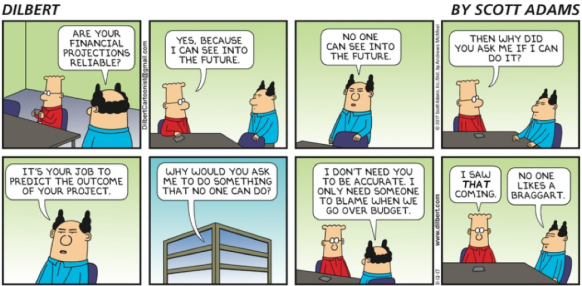

Source: Dilbert (11.12.17)

Note the 2017 S&P 500 forecasts by 20 of Wall Street’s leading firms and strategists shown below (fuller data is available here, here, here and here). They are truly dreadful.

| Bank of America (Savita Subramanian) | 2,300 |

| Barclays (Jonathan Glionna) | 2,400 |

| BlackRock (Heidi Richardson) | 2,400 |

| Blackstone (Byron Wein) | 2,500 |

| BMO (Brian Belski) | 2,350 |

| Citi (Tobias Levkovich) | 2,325 |

| Jeffrey Knight (Columbia Threadneedle) | 2,450 |

| Canaccord (Tony Dwyer) | 2,340 |

| Credit Suisse (Lori Calvasina) | 2,300 |

| Deutsche Bank (David Bianco) | 2,350 |

| Federated Investors (John Auth) | 2,350 |

| Goldman Sachs (David Kostin) | 2,300 |

| Jefferies (Sean Darby) | 2,325 |

| JPMorgan (Dubravko Lakos Bujas) | 2,400 |

| Morgan Stanley (Adam Parker) | 2,300 |

| Prudential International (John Praveen) | 2,575 |

| Oppenheimer (John Stoltzfus) | 2,450 |

| RBC (Jonathan Golub) | 2,500 |

| UBS (Julian Emanuel) | 2,300 |

| Societe Generale (Roland Kaloyan) | 2,400 |

| Median Forecast | 2,350 (+3.5 percent) |

| Actual Result 2017 | 2,673.61 (+19.42 percent)

+21.64 percent |

These are really smart, experienced people who analyze the markets pretty much all day, every day. And they missed by a mile. In fact, the best of them missed by a mile.

In short, almost all “experts” were calling for 2017 to be primed for the “reflation trade,” consisting of bond yields, the dollar and stock prices all moving higher, driven by rising wages and President Trump’s tax-cut plans, seasoned with lots of volatility because of the political and geopolitical uncertainty. However, as 2018 dawned, inflation hadn’t appeared, tax legislation just got done under the wire, and the analysts were wrong (benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note yields were down a touch, not up), wrong (the dollar was down about 10 percent, not up), only partly right (the S&P 500 has delivered more than double the gains of even the most bullish Wall Street prognosticator), and wrong (the lack of volatility was record-setting, despite plenty of uncertainty).

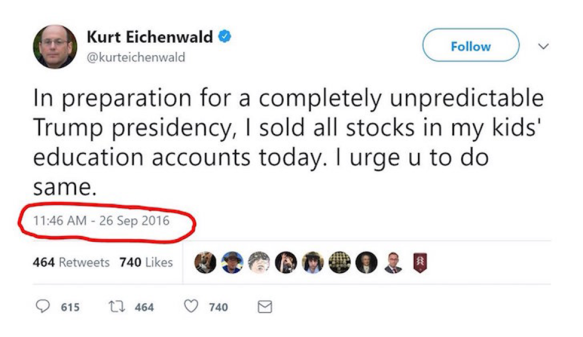

When market predictions are mixed with politics, the results are usually even worse, if that were possible. For example, after the most recent presidential election (about 14 months ago), when his preferred candidate did not win, Nobel Prize winning economist (but progressive political activist) Paul Krugman forecast dire things, proclaiming President Trump to be the “mother of all adverse effects.”

“It really does now look like President Donald J. Trump, and markets are plunging. When might we expect them to recover?

“Frankly, I find it hard to care much, even though this is my specialty. The disaster for America and the world has so many aspects that the economic ramifications are way down my list of things to fear.

“Still, I guess people want an answer: If the question is when markets will recover, a first-pass answer is never.”

He called for a “global recession” too. It hasn’t exactly turned out that way.

Of course, our human weakness with respect to forecasting the future is hardly limited to the markets. For example, ESPN had its 35 “experts” – people whose whole job is to follow and pontificate about Major League Baseball – predict the outcome of the 2017 season. Not a single one of them called for an Astros v. Dodgers World Series and nobody had Houston winning it all. None. Nada. Squadouche.

So if you think you can predict the future in the markets, think again. Your crystal ball does not work any better than anyone else’s. Even when we recognize the fallacy of thinking in terms of single, linear causes (Fed policy, market valuations, etc.), the markets are still too complex and too adaptive to be readily predicted (as we have already seen). There are simply too many variables to predict market behavior with any degree of detail, consistency or competence. Pretty much the only forecast that is almost certain to be correct is that market forecasts will be wrong (and if they are right, it’s probably because of luck rather than skill).

Why an “Outlook” at all?

We may be lousy at investment forecasts (and we are), but the idea that we can live our investing lives forecast-free is as erroneous as the market predictions that are so easy to mock. As Cullen Roche emphasizes, “any decision about the future involves an implicit forecast about future outcomes.” As Philip Tetlock wrote: “We are all forecasters. When we think about changing jobs, getting married, buying a home, making an investment, launching a product, or retiring, we decide based on how we expect the future to unfold.”

It’s a grand conundrum for the world of finance — we desperately need to make forecasts in order to succeed but we are remarkably poor at doing so. What should we do with that knowledge. Why an Outlook at all?

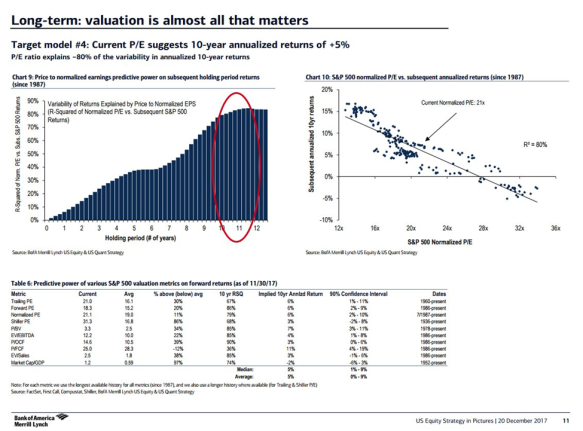

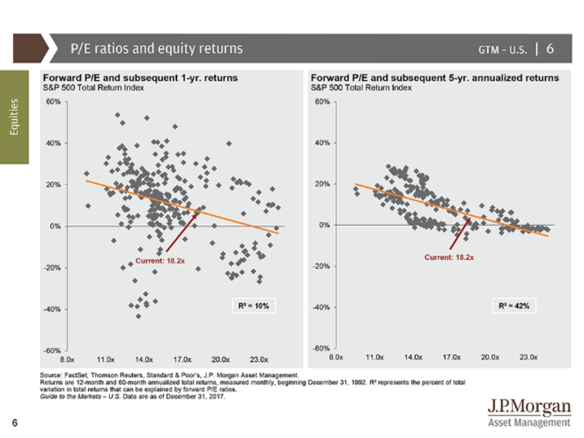

There are three primary reasons. The first is that doing so is interesting and fun. It forces serious consideration of what has gone on and what’s going on. That is a valuable exercise. Secondly, longer-term outlooks (and especially those based upon appropriate valuation measures) do have a history of very rough accuracy. We can have almost no idea of what will happen in the near-term while still having a pretty good idea of what investment prospects and returns should look like over the next 5-10 years. Finally, a good Outlook can remind us where we are and highlight the trends and possibilities we are most likely to face going forward. There are so many variables and “unknown unknowns” (to use Donald Rumsfeld’s famous phrase) that we will necessarily be wrong a lot. Nobody can offer Truth with a capital “T.” But it is possible to be helpful. It’s a modest but important goal.

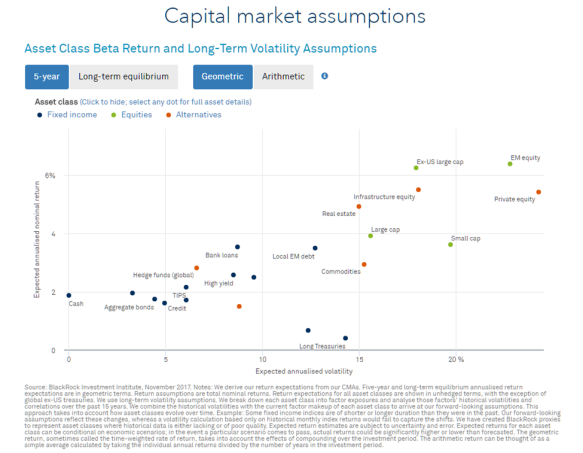

Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions

Long-term financial planning requires some measure of expected investment returns. Unfortunately, we can have almost no idea of what will happen in the markets over the near-term. As Nobel laureate Robert Shiller (from the first edition of his classic, Irrational Exuberance) explained, “The U.S. stock market ups and downs over the past century have made virtually no sense ex post. It is curious how little known this simple fact is.” It is true that market valuations are high (more on that below). Yet even that knowledge tells us essentially nothing about near-term returns.

However, we can ascertain a very rough idea of what investment prospects and returns should look like over the next 5-10 years – long-term capital markets assumptions – based upon a variety of factors. These calculations can be quite valuable and roughly accurate.

Most current LTCMA are similar to those of Yale Endowment head David Swensen, who is currently expecting future returns for his Yale portfolio in the range of five percent per year (adjusted for inflation), despite long-term annual performance by his portfolio of well above 13 percent. The key driver of these assumptions is equity valuations.

Even nine years into one of the strongest stock market recoveries in history, “this bull market is not over yet,” argues Jeremy Siegel, University of Pennsylvania finance professor and author of the 1994 classic, Stocks for the Long Run, now in its fifth edition, which helped cement the conventional wisdom that stocks are a great investment choice. Siegel insists that the “stock market is fairly valued now” but he also expects it to deliver a five percent real annual returns going forward.

By most measures (Siegel notwithstanding), stocks are rich, but so are bonds. Thus, the current rally is backed by solid fundamentals, but also by a lack of compelling alternatives.

The relevant conclusion is, in my view, a simple one. There is no current reason to exit the markets, especially for long-term investors. Longer-term returns are likely to be below their longer-term averages. There is risk, as there always is to a greater or lesser extent. Drawdown risk is the price that must be paid for the much higher historical returns provided by stocks as opposed to any other investment alternative. Accordingly, investors would be wise to make hay while the sun shines.

Looking Ahead

In this section, I will examine what I will be looking for and at in 2018.

The Markets

In the U.S., high valuations have made investors cautious, such that companies that consistently produce earnings growth are being rewarded while those that don’t are being punished, even as the market as a whole has powered higher and the overall economy continues to strengthen. That sorting is a good thing generally, but makes things harder for active money managers. I don’t expect the end of the rally to be upon us, but I think we’re a lot closer to the end than to the beginning.

In terms of fixed income, I don’t see much reason to be bullish given the absolute level of rates, but I don’t expect a precipitous rate rise either, despite the chance that we might see some meaningful inflation start to appear in 2018. I see a “low-for-longer” theme playing out. Rates may continue to drift higher – and probably will – but the highest rates we’re likely to see this cycle will still be fairly low on a historical basis.

Supporting this view isn’t just the Fed’s ability to control the advance to this point (in that context, I expect Fed balance sheet compression to begin in earnest and probably two or three more rate hikes in 2018, even though the futures markets suggest it’s more like 1.5), it’s also that U.S. fixed income remains relatively attractive globally. Japanese 10-year interest rates are effectively zero while German interest rates are less than half-of-one percent. In comparison, a 2.4 percent yield on a 10-year U.S. Treasury note (the year-end 2017 rate) is relatively attractive. High yield and corporate paper face the same valuation issues that equities do, but Treasuries should do okay and the yield curve should flatten some more. That said, yields are hardly appetizing. So reaching for it will likely continue, despite the dangers.

A few more specific thoughts on the year ahead in the markets follow.

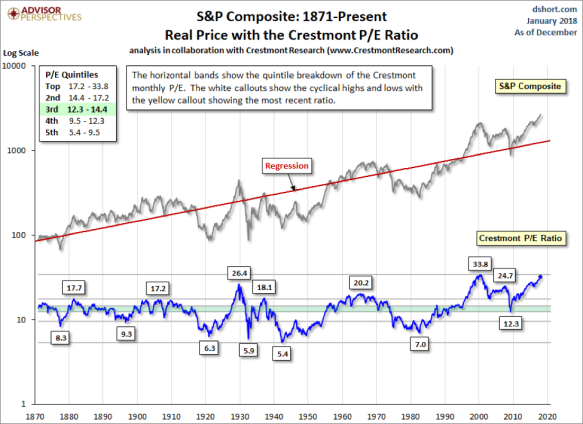

Valuations. By most measures, stock market valuations are quite high, as I have noted repeatedly.

That does not bode well for long-term future returns.

That does not bode well for long-term future returns.

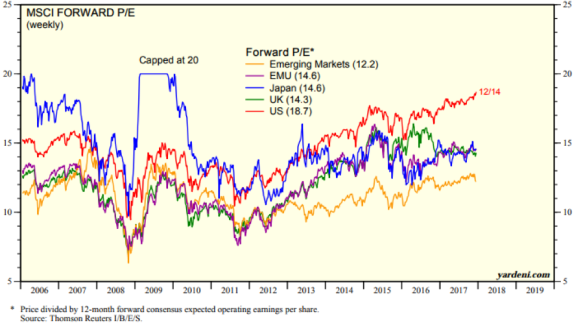

To be sure, valuations tell us very little about market performance in the short-term. However, while in the short-term the market is a sort of voting machine, over the longer-term it is a weighing machine. Valuations matter and should be watched carefully. Moreover, the best current values are overseas.

Source: Yardeni Research

Source: Yardeni Research

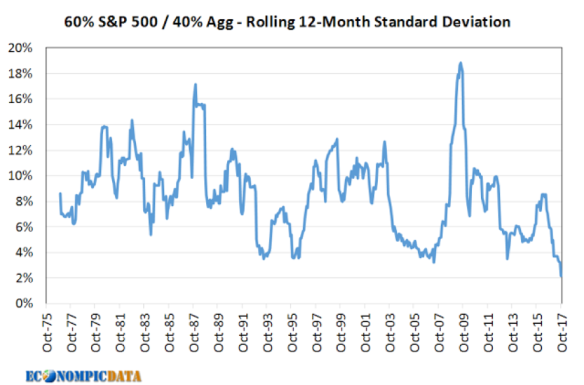

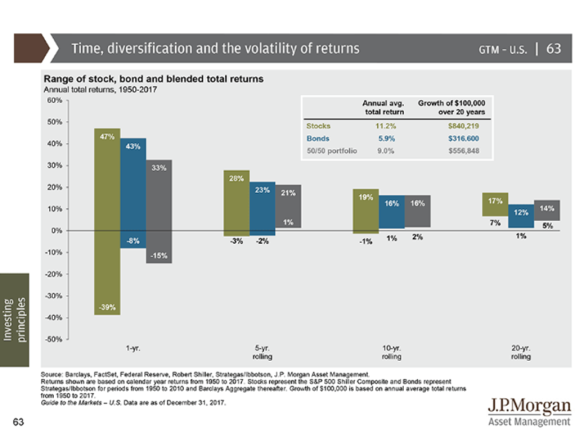

Volatility. As noted, the markets have been inordinately quiet. Since the February 2016 lows, a 60/40 portfolio consisting of the S&P 500 and the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index had a 12-month standard deviation of just 2.2 percent ending October 2017, the lowest period of volatility since the inception of the aggregate bond index back in 1976.

In 2017, for the first time ever, the S&P 500 provided positive returns in every calendar month.

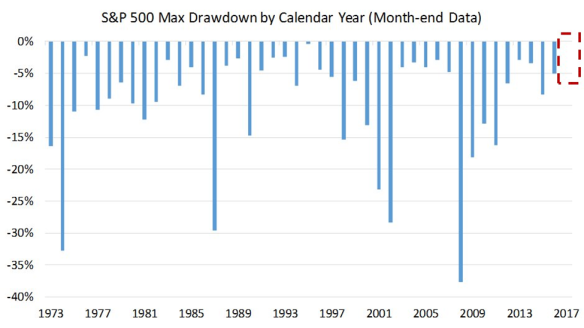

As a result of the markets being so calm for so long – stocks have traded essentially straight up since March 2009 – there has been a significant increase in risk-taking. Moreover, as Econompic has carefully shown, investors who have entered the market over the past 20 years have lived through two of the four big market drawdowns over the past century, but neither event was likely to have been all that costly to them in dollar terms (because investors rarely have significant sums invested during their early investment years).

The long-term lack of volatility we have seen has provided a false sense of security for many. Accordingly, when the next big market correction comes – and it will come eventually, and perhaps much sooner than we expect – all of us will feel it particularly strongly and some of us will be overwhelmed by it.

Currency. The U.S. dollar was riding high as 2017 opened, and most expected that trend to continue. However, the buck spent most of the year dropping, even as the Federal Reserve raised rates. That has been good news for stocks. The dollar’s weakness has come as the global outlook has brightened, in particular in Europe and emerging markets, driving investment in foreign markets. In 2018, will a soft dollar continue to support traders’ appetite for risk?

Where Might I Be Wrong? It should be obvious, based upon the research I have provided, that I could be wrong in any number of ways. The sad fact is that, as Carla Gentry recently explained, “The world is not always logical. Human emotion and sentiment adds a complex layer to data analysis that requires greater context to the information that is collected.” I should emphasize that I am not always logical. I could be wrong. What follows is a particularly fraught example (courtesy of the brilliant Ben Hunt) of how I could be wrong.

Former Fed chair Ben Bernanke was clear about why the Fed has maintained easy money since the global financial crisis.

“Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.”

That action – designed to drive stock and bond prices higher and to force people who needed it to reach for yield – has worked in that markets stabilized and those with financial assets did very well.

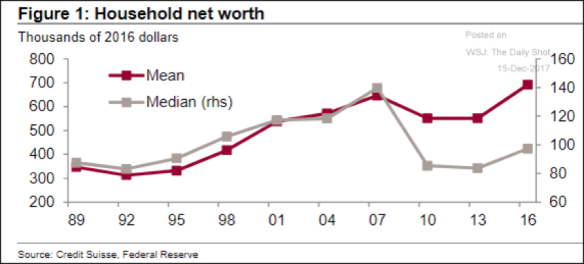

At nearly nine years old, the post-financial crisis bull market is now the second-oldest and second-strongest in history. It has created significantly more wealth for many households. Moreover, due to the “magic” of compounding, the more financial assets one had, the better one did. On average, investors in the S&P 500 have earned more than 17 percent per year since March of 2009, at the depths of the financial crisis. However, many Americans have not felt the stock market boom because they have little or no money invested in the market. Just 18.7 percent of taxpayers own stocks directly while only about half of Americans participate in the market through an employee-sponsored retirement plan, according to a Pew analysis of Census Bureau data. That gap has contributed to record-high wealth inequality in America.

In different ways, wealth inequality was at least partially behind the populist wave we have seen in the last couple of years among both American political parties. It supported the Trump boom, albeit far from linearly. According to Fed data, aggregate household debt balances rose by $116 billion in the third quarter of 2017. As of September 30, 2017, the most recent available data, total household indebtedness was $12.96 trillion. This increase put overall household debt $280 billion above its 2008 Q3 peak, and 16.2 percent above the 2013 Q2 trough.

In other words, cheap money has made it possible for non-rich people to feel rich with houses, cars and iPhones, but those things don’t appreciate. College is often made available, too, but also by crushing debt. Over 44 million Americans have $1.5 trillion in student loan debt. The average 2016 graduate has over $37,000 in student debt, up six percent year-over-year (data here, here, here and here). Let them eat cake, indeed.

If and as interest rates continue to rise, new and floating rate obligations will become increasingly harder to get and difficult to pay, making life even more difficult for the non-rich. This situation is a recipe for disaster as “the ratio of people to cake” gets too small.

It isn’t immediate or even likely, perhaps, but the put-upon poor might well decide to burn the place down. That idea was already behind a surprising number of Trump voters. The tax reform bill will provide a bit of relief for many. But it isn’t hard to imagine a scenario where it’s hardly enough. The prototypical Trump voter in Michigan, Ohio or Wisconsin may have hoped to see his or her life impacted directly and significantly by the Trump presidency, but isn’t likely to have seen it so far. In that context, burn it all down (which we have seen before) will not likely be a good outcome for the country or the markets.

Another plausible contrary (and related) outcome begins with market players consistently chasing growth and yield in a bull market that’s been driven and enabled by central bank liquidity. When profits peak, market positioning will likely be excessively enthusiastic as central banks withdraw liquidity and scale back support. That’s a dangerous inflection point. This bull market in the S&P 500 is on a path to become the longest ever on August 22, and if equities outperform bonds for a seventh consecutive year in 2018, it would be the first time since 1928.

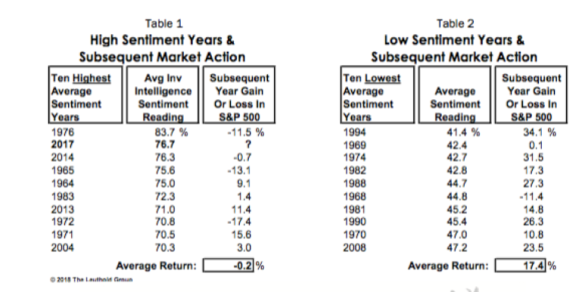

Finally, I could be wrong because the herd is so often wrong.

I’m much more comfortable as a contrarian than when I am in the majority. I’m in the majority this year. That makes me nervous.

The Economy

Disruptive Innovation. Today’s world is increasingly networked. We are not too very far from a digital ideal (which might be a nightmare) where everyone and everything are intimately connected. One apparent consequence of that reality is that our institutions (along with everything else) are subject to disintermediation and decentralization. Accordingly, these traditional hierarchical structures – such as states, churches, political parties, the press and, most importantly for these purposes, industries, companies and brands – are in various states of crisis and decline. More on that below. Thus disruptive innovation is easier, faster and more powerful than ever before. It creates new winners and losers in ways that are often surprising and perhaps inherently unpredictable.

As ever, disruptive innovation will impact companies and markets in 2018 both in ways that might be anticipated and in ways that will not be. For example, we can see that web retailers have been developing their own brands and selling their products through voice-activated assistant devices with the advantage of proprietary data. Moreover, we can anticipate further disruption among consumer staples companies because the internet has broken down traditional barriers to entry.

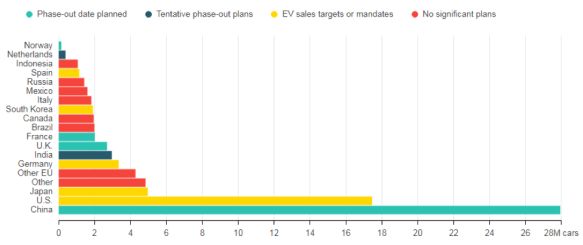

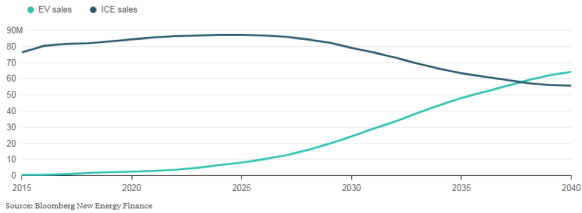

Longer term, it isn’t hard to expect disruption of various sorts impacting every business sector. One doesn’t have to think that Tesla is a great investment to see autos as a prime candidate to follow consumer staples as a disruption candidate. So what will disruptive innovation look like in 2018 and beyond? I will be watching closely.

The Impact of Tax Reform. Just before Christmas, President Trump signed the Republicans’ long-awaited tax proposal into law. This legislation decreases taxes for corporations, modifies various tax deduction options, and provides lower individual tax rates.

At the corporate level, the legislation will result in substantive tax reform, with the elimination of the AMT and overall consolidation down to a single 21 percent tax rate. This is the clearest advantage of the new law, in that it makes the U.S. more competitive with other developed nations. The 2017 rate (pre-reform) was the highest corporate tax rate in the industrialized world.

At the individual level, the new legislation is more of a series of adjustments, which will be subject to sunset provision after 2025. Still, these new tax laws have much to like for individual households, almost all of whom (over 80 percent) will see a reduction of taxes in the coming years (though not after the 2025 sunset). While seven tax brackets remain, most are decreased by a few percentage points (to a top rate of 37 percent). A doubling of the estate tax exemption amount – to $11.2 million for individuals and $22.4 million for couples with portability – will make estate tax planning irrelevant in 2018 and beyond for all but the wealthiest of taxpayers.

Several of the more unpopular provisions from the original bill, such as eliminating deductions for student loan interest, major medical expenses as well as teachers’ supplies, and treating tuition waivers as taxable income, didn’t make it into the final draft. The final bill, unlike either the original House or Senate versions, also retains partial deductibility of state and local income taxes. Still, Speaker Paul Ryan made the main case for the legislation after House passage: “In February, [Americans] are going to see withholdings go down so they see bigger paychecks.” On the other hand, despite administration claims that it “would pay for itself,” analysis of the tax cut legislation (see here, here, and here) generally places the revenue loss as between $500 billion and $1.5 trillion, increasing federal debt and deficits substantially.

The tax law changes will likely have a significant impact on the markets. In general, the new law should be incrementally good for stocks and less good for bonds, should marginally lower unemployment even further, and should juice consumer demand somewhat. The repatriation provision coupled with the lower corporate tax rate should make American businesses more competitive, support some additional corporate spending (some of which we are already seeing), improve corporate earnings (and especially earnings per share), fund additional stock dividends and buybacks, and spur some M&A activity. The reduction in corporate tax rates should also help smaller companies more than the behemoths because smaller companies generally pay higher effective tax rates and have more limited access to various “loopholes.”

Congress has added fiscal stimulus to an already noteworthy list of positive attributes to the global economy. Once the effects of the tax plan stimulus begin to wane – late in 2019 or 2020 – recession becomes more likely. As ever, the costs of added debt and deficit are kicked down the road. However, in the near-term, at least, things look rosy indeed.

There is an important caveat to be noted. This legacy-defining tax bill approved without a single Democratic vote polls as historically unpopular today. Democrats seem to have oversold the idea that tax cuts will only go to rich people. We’ll see if that messaging success sticks.

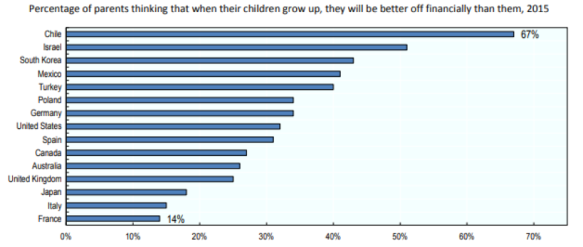

Inequality. Social and economic mobility are very good things. We should want people to be able to achieve irrespective of their current circumstances. However, and the world over, parents today are less inclined to believe that their children will do better than they have done.

Source: Pew Research Center, Global Indicators Database

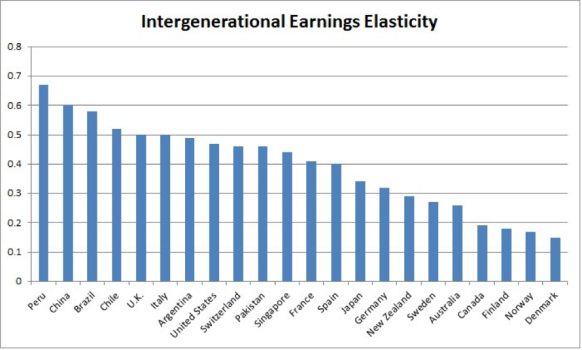

This aspiration also isn’t playing out in the U.S. in the way we would like. The U.S. numbers aren’t the worst, but the correlation between American parent and child incomes (showing a lack of economic mobility) is still above most other OECD countries.

Source: University of Ottawa/Miles Corak

These statistics are especially troubling for Americans in that the “American Dream” has been central to our collective self-image for our entire history. Yet, despite our ideals, income inequality is increasing (and is increasingly a bad thing for the poor). American wealth is growing substantially, but median wealth – indicative of economic mobility – is declining.

For America fully to be the world’s economic juggernaut, opportunity must be available to everyone: rich and poor alike. That isn’t happening today and bears watching going forward.

USA

Elections. President Trump is historically unpopular (albeit less unpopular than major European leaders in their countries). The realities of mid-term elections (the President’s party tends to do poorly), together with Mr. Trump’s lack of popularity favor Democrats in the 2018 elections, but the set-up of the electoral map and the lack of a clear leader or a clear message militate against Democrats being nearly as successful as they ought to be. This bears watching.

Polarization.

Watching five minutes of cable news is usually enough to establish that Americans have never been as divided along partisan lines as they are now. A new Pew Research Center study gives empirical support to that idea and shows that the nation’s political cleavages on most issues got even wider during the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency. The gap between Democrats and Republicans continues to expand on a wide variety of questions on topics such as the role of government, race, immigration, and where they prefer to live. Moreover, each party has become more ideologically homogeneous and more hostile toward the opinions of members of the other party. The widening gap between Democrats and Republicans isn’t just a short-term trend, either.

I don’t think that is healthy for America and fear that it is unsustainable. It makes cooperation all but impossible. Instead, we get perpetual outrage pretty much across-the-board. But I don’t expect things to change in this regard either. That is a potential problem with huge potential consequences going forward.

Institutions. Since 1973, Gallup has been polling citizens about their confidence in America’s institutions, such as the Presidency, organized religion, and public schools. Over that time, the project demonstrates a seemingly inexorable collapse in public trust. In 1973, more than four in ten Americans had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in Congress. This year, the figure was 12 percent. Trust in the presidency has declined such that while only 14 percent of Americans had “very little” confidence in it in 1975, the year after President Nixon resigned because of the Watergate scandal, fully 42 percent of respondents have “very little” confidence in the presidency in 2017.

The polarization and tribalization of today’s politics (described above) surely exacerbates and contributes to this loss of confidence in America, as lived out by and among our leading institutions. So does our interconnectedness. Let’s take a more detailed look at one major example.

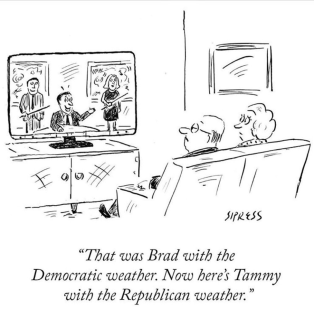

Journalists are overwhelmingly Democratic (see here, here and here, for example). Indeed, just seven percent of journalists are Republicans. One advice columnist for a major publication even suggested that boyfriends be dumped for voting Republican. That reality alone is a major problem.

However, many Republicans – led by President Trump – routinely say that the “liberal media” intentionally lies about Republicans. But that story doesn’t hold up. The failed sting of The Washington Post by conservative activists demonstrates that pretty clearly. Moreover, no news organization ignored the Clinton emails story or the damaging John Podesta email cache that WikiLeaks served up. However, the threat of a biased media is real and much more insidious.

Pretty much all members of the national press live and work in blue states and in the bluest counties within those blue states. If you’re a working journalist, odds aren’t just that you work in a county that was pro-Clinton, odds are that you reside in one of the nation’s most pro-Clinton counties. Back in 2004, Daniel Okrent of The New York Times acknowledged the decidedly liberal bent of his newspaper’s staff and noted that the “heart, mind, and habits” of the Times cannot be separated from the ethos of the cosmopolitan (deep blue) city in which it is created. As Pauline Kael of The New Yorker famously said in 1972, “I live in a rather special world. I only know one person who voted for Nixon. Where they are I don’t know. They’re outside my ken. But sometimes when I’m in a theater I can feel them.” The Times seems unable even to find any Trump supporters.

This lack of diversity plays out in what and how stories are reported.

In one December week alone, four huge stories run by major news organizations turned out to be false (note that I am not including more minor errors, like the erroneous crowd size photo tweeted by a reporter from The Washington Post that same week or, my personal favorite, a Politico article describing the “falling out” between President Trump and his former Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, the correction to which screams to be quoted: “CORRECTION: An earlier version of the story misidentified the fictional character name Bannon uses to refer to Jared Kushner [the President’s son-in-law] as Frodo, a “Lord of the Rings” reference, rather than Fredo, a reference to “The Godfather”).

The errors to which I am referring are very major ones indeed. Reuters, Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journal, and others reported that the special counsel’s office had subpoenaed Deutsche Bank seeking President Trump’s banking records. They didn’t. ABC reported that the president had directed subsequent (and now former) National Security Advisor Michael Flynn to contact Russian officials before the election. He didn’t (as far as we know to this point). The New York Times ran a story that had Deputy NSA K.T. McFarland acknowledging collusion. She didn’t. Then CNN topped off the week by falsely reporting that the Trump campaign had been offered access to hacked Democratic National Committee emails before they were published.

Press apologists will assert that these errors were just that – errors – and are not evidence of intentional misrepresentation. But note that these errors are all “in the same direction” and within the context of constant, overwhelmingly negative press coverage. They all portray President Trump in an unfavorable light. There is thus very good reason to believe that these news organizations are so anxious to oppose the president that they readily fall for bogus stories, which Rich Lowry calls “too anti-Trump to check.” This is strong evidence of bias, pure and simple. It may not be intentional, but it is evidence of biased groupthink – which is to be expected because American reporters generally live and work in deep blue echo chambers.

To be sure, President Trump is highly controversial. He has a difficult, often non-existent relationship with the truth. We have gone from “fake news” being bizarre, unsubstantiated smears (such as President Obama being a Muslim born outside this country or the father of Senator Ted Cruz being part of the conspiracy to kill JFK), to becoming any media coverage the president doesn’t like.

His tweets are often destructive, too. He loves toadyism. And perhaps Special Counsel Robert Mueller will discover evidence so as to demonstrate that the Trump campaign colluded with Russia. However, unlike the previous administration, Team Trump has not undermined the ability of the press to report stories accurately and has not attempted to silence a reporter by making a claim of espionage. Moreover, while President Trump’s approval ratings are very poor, they are better than recent poll numbers for respected foreign leaders such as Angela Merkel of Germany, Emmanuel Macron of France, Canada’s Justin Trudeau, and Theresa May of Great Britain, who all receive good-to-fawning coverage by the American press. Former President Jimmy Carter has even said, “I think the media have been harder on Trump than any other president certainly that I’ve known about.”

If, as the “resistance” alleges, the Trump presidency is a major catastrophe that threatens the foundations of our republic, the American experiment will survive and thrive to the extent that its institutions survive and thrive. Unfortunately, the press is widely discredited by a huge percentage of Americans. That status is well-earned. Accordingly, the press (as with all our major institutions) has major work to do to regain sufficient status effectively to speak truth to power. That requires a press that is and is perceived as being fair. That requires fewer opinions and less emotion. Based upon the evidence of press coverage during 2017, things need to get a lot better. I’ll be watching to see if they do.

“Techlash.” Daniel Franklin, executive editor at The Economist and editor of “The World in 2018,” told CNBC that he was looking for an impending “techlash.” According to Franklin, lawmakers across the globe are likely to turn on tech behemoths such as Facebook, Google and Amazon. “These companies have [become] worryingly large, their use of data isn’t always something people are happy with and there’s the whole question over whether their platforms are being used for political purposes,” he added.

Per Snap CEO Evan Spiegel: “The personalized news feed revolutionized the way people share and consume content. But let’s be honest: This came at a huge cost to facts, our minds, and the entire media industry.” That Silicon Valley often seems tone deaf to what’s happening makes matters worse. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg issued a 6,000-word manifesto about the positive role Facebook could have reshaping global society but sent his attorney to Congress to answer questions about Facebook’s negative influence on that global society.

Of course, the list of Silicon Valley sins is a long one. There is a pervasive history of misogyny, often disguised by pretentiously pretending to be about “a new paradigm of behavior.” There is a long-term refusal to try to prevent falsehoods and abuse. There is the ongoing fear of digital media censorship of voices they do not like under the guise of preventing falsehoods and abuse. And there is the brute fact that most of us were hacked in one form or another in 2017.

The tech industry has been perhaps the primary disruptive force in the world economy over the past couple of decades. But it can be disrupted too – by an angry customer base tired of abuse, being taken for granted, and having its privacy violated again and again, by a government looking to regulate behavior seen as dangerous and predatory to security and its citizens, or by competitors looking for an edge. I’ll be watching this carefully in 2018.

#Me Too. “#Me Too” spread virally on social media in October as a powerful means to denounce sexual assault and harassment in the wake of sexual misconduct allegations against film producer and executive Harvey Weinstein. The hashtag was popularized by actress Alyssa Milano, who encouraged women to tweet it to publicize experiences to demonstrate the widespread nature of sexual abuse and misogynistic behavior. It has been used millions of times, often with an accompanying personal story of sexual harassment or assault. The response has included many high-profile posts and articles by prominent A-listers.

More broadly, according to data from the United Nations, 35 percent of the world’s women have been the victims of physical and/or sexual violence. To make matters worse, the playing field is absurdly uneven. Worldwide, on virtually every metric (lower pay, more unpaid work, less access to education and health care, greater rates of malnourishment, and more) women fare worse than men.

The “#Me Too” movement has spread from entertainment to media to politics to academia and throughout the world, with no sign of relenting. It now even includes a substantive response to an undeniable problem. This sort of grass roots movement (like 2011’s “Arab Spring” uprising and the current – and fledgling – protest movement in Iran) is inherently unpredictable. But its potential is as enormous as the need is great. It will be well worth watching.

The World

Hot Spots. As noted in the 2017 review above, the world had many hot spots in 2017. Some areas – the Middle East comes prominently to mind – seem always to be on the list. These hot spots are numerous, of course. After more than six years of conflict, roughly half a million dead and 12 million displaced, deadly Syrian President Bashar al-Assad still appears likely to maintain power. ISIS is not likely to give up. The war in Yemen has created another humanitarian catastrophe, wrecking a country that was already the poorest in the Arab world. Overlapping conflicts to the immediate south of the Sahara Desert have contributed to massive human suffering, including the uprooting of some 4.2 million people from their homes.

War and political instability in Afghanistan continue to pose a serious threat to international peace and security after more than 16 years of war. After four years of war, Russia’s military intervention defines all aspects of life in Ukraine, which remains divided by the conflict and crippled by corruption. These locations, the others perviously discussed, and the new problem areas that will undoubtedly crop up in 2018 bear close monitoring going forward.

Globalization. In economic terms, globalization provides a clear net benefit to individual economies around the world by making markets more efficient, increasing competition, limiting military conflicts, and spreading wealth more equally around the world. However, the general public tends to assume that the costs associated with globalization outweigh the benefits, especially in the short-term, thus making protectionism attractive. Some of the benefits of globalization include foreign direct investment, technological innovation, increased competition, lower consumer prices, and increased economic growth. Although globalization helps strong countries like the U.S. more than its weaker competitors, smaller businesses here sometimes find it difficult to deal with foreign competitors, making free markets less attractive. Since President Trump has rejected the traditional Republican commitment to free markets, the trend toward globalization – which seems inexorable despite anything the President may attempt – bears careful examination going forward.

Climate. According to nearly all working scientists in the field and the various organizations representing America’s best scientists, climate change is a fact. It is very likely caused by the emission of greenhouse gases from human activities and poses significant risks for a range of human and natural systems. As these emissions continue to increase, further change and greater risks will ensue. These risks include rising temperatures, rising seas, extreme weather, and the problems caused or (more typically) exacerbated by them.

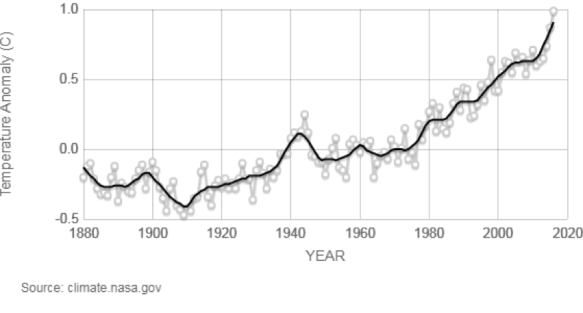

One can surely question the policy implications of climate change. I certainly do. However, there is no disputing the following. Temperatures are rising.

Carbon dioxide levels are rising.

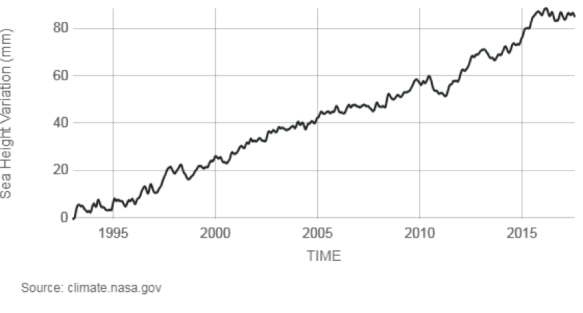

Sea levels are rising.

Weather is and has been extreme. Events like 2017’s unprecedented number of severe hurricanes have made it exceedingly difficult to ignore the increased and intensifying storms, droughts, cold snaps, heat waves, wildfires and disease that inevitably follow from climate change and which are causing devastating damage and disaster-related losses, according to organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It also means more agriculture-related problems and more variability in weather patterns. Since President Trump rejects the science of climate change, and since the policy proposals of the Democrats in response to climate change do not primarily focus upon innovation but, instead, to the extent they have anything like a plan, would primarily impede economic growth via regulation, this problem seems intractable, at least for now. It bears watching.

The Unknown

The highly improbable happens all the time. Think about that for a bit. In fact, much of what happens is highly improbable. Only an extreme longshot wins the lottery – but people win. This math explains why we shouldn’t be surprised when the market remains “irrational” far longer than seems possible. But we are. The world is far more random than we’d like to think. Indeed, the world is far more random than we can imagine.

In what is now a ubiquitous concept, a “black swan” is an extreme event – good or bad – that lies beyond the realm of our normal expectations and which has enormous consequences (e.g., Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”). It is by definition an outlier. Examples include the rise of Hitler, winning the lottery, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the ultimate demise of the Soviet bloc, the development of Viagra (which was originally designed to treat hypertension before a surprising side effect was discovered) and, of course, the 9.11 atrocities.

In 2018, we might see a major cyber-attack. Or a “quant quake.” Or something else. What unknown unknowns will come to the fore in 2018?

Best Ideas

WARNING: The following is real security camera footage and it is truly horrible.

In August of 2010, while visiting a shopping center in Daejon, South Korea, a 40 year-old wheelchair-bound man identified only as “Mr. Lee” just missed an elevator when the doors closed on him a moment too soon (as shown above). Angered at his misfortune, Lee backed up his motorized chair and rammed into the elevator doors. Unsatisfied at merely denting the object of his rage, Lee backed up and acted as human battering ram again. He “succeeded” this time, crashing through the doors and plunging to his death. Not surprisingly, shopping center officials vowed to strengthen the doors of their elevators in order to protect future morons.

If you’re like most people, you probably aren’t sure whether it’s appropriate to laugh at Lee’s stupidity or simply to despair at the loss of life (as well as the depth and extent of human stupidity). While most are not as flagrant as this one, it isn’t hard to find myriad examples of really bad ideas. We humans are shockingly susceptible to bad ideas, ideas that routinely grow into poor decisions and then metastasize into behavior that may undermine, severely damage, ruin or even end our lives. Conversely, really good ideas are surprisingly hard to find. I will try to offer a few for 2018.

Perennials