Note: A version hereof will appear in my ninth annual Investment Outlook. Watch this space.

We are all natural-born and equal opportunity extremists who want to live in exceptional times. That is why, for example, in the financial world, we regularly overpay both for insurance and for lottery tickets (literal and figurative). We are pulled toward extremism by our inherent biases, including tribalism, herding, excessive certainty, and overconfidence. The problems caused by these biases are compounded by our ideological nature, our propensity for confirming what we already believe, and our general inability to see that which disconfirms it. The sad truth is that none of us is as good as we think we are. We postulate apocalyptic conclusions irrespective of whether there is good support for them.

Evidence of this obsession abounds.

John Hussman is a smart guy. He is a Stanford Ph.D. who became Professor of Economics and International Finance at the University of Michigan before setting up his own asset management firm, Hussman Strategic Advisors. His anticipatory apocalyptic call on the 2008-2009 financial crisis was right on the money, brought in lots of money, and made him a ton of money. High on that success, as of September 2010, Hussman managed $6.7 billion.

Unfortunately for Hussman, the apocalypse was always nigh to him, irrespective of facts. While Robert Frost reminded us in 1923 that “nothing gold can stay,” Hussman’s insistence that the markets offer mostly fool’s gold is at least equally wrong (representative performance samples below; analytical example here).

- 2010: “Investors dangerously underestimate the risk of an abrupt and possibly severe equity market plunge.”

- 2011: “the expected return/risk profile of the stock market has shifted to hard-negative.”

- 2012: “The present menu of investment opportunities continues to be among the worst in history.”

- 2013: “stock returns prospectively are very low.”

- 2014: “What concerns us beyond valuations is the full ensemble of overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions.”

- 2015: “Exit now.”

- 2016: “current extremes imply 40-55 percent market losses…. These are not worst-case scenarios, but run-of-the-mill expectations.”

- 2017: “the most broadly overvalued moment in market history.”

- 2018: “The music is fading out, and a trap-door has opened up in the floor, but they’re still dancing.”

- 2019: “a projected 50-65 percent market loss over the completion of this cycle is actually somewhat optimistic.”

Obviously, Hussman turned into a “perma-bear,” calling for disaster constantly (and wrongly). Hussman still insists that he will be vindicated, and criticizes those who would “declare victory at halftime.” He criticized “declaring victory at halftime” previously six full years ago (that’s one long halftime). Hussman wants us to believe that he’s not wrong, merely right but early. However, if you keep making the same wrong call over and over, you don’t get any credit for it when you’re (eventually) right. After ten years, even “right but early” has to have become “wrong.” Even a stopped clock is right twice per day.

Through 2019, Hussman’s Strategic Growth fund has suffered a 10-year average annual “return” of -7.54 percent, compared to a 13.24 percent average annual gain by its benchmark, the S&P 500. Despite exceptional early returns, the fund not only badly trails the S&P since inception, it is now a money loser since inception. Notwithstanding this terrible performance, Hussman keeps charging investors 1.25 percent annually to lose their money. Not surprisingly, outflows began in earnest in 2011, picked up in 2012, and have been steady since. His current assets under management have declined from $6.7 billion to barely $250 million.

For Hussman, his negativism seems to have evolved over time into an ideological commitment to his rightness, despite the obvious evidence, with horrific results. Ideology, most obvious within politics, readily leads to bad market forecasts and bad results. A few easy and recent examples follow.

An op-ed in The Wall Street Journal by Republican economist Michael Boskin, on March 6, 2009, carried a headline which said it all: “Obama’s Radicalism Is Killing the Dow.” It was almost perfectly timed to the bottom of the market. The S&P 500 gained 232 percent from the time Boskin’s op-ed appeared to the day President Obama left office. Similarly, then private citizen Donald Trump was wildly wrong when he projected via November 2012 tweetthat both the stock market and the U.S. dollar would plunge following Mr. Obama’s second victory (the S&P 500 rose almost 50 percent during President Obama’s second term, bringing his two-term return to 112 percent, while Bloomberg’s dollar index gained 21 percent in the four years that ended in November 2016). Of course, terrible predictions are not limited in political outlook. On the day after the 2016 election, economist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman called for economic and market disaster: “If the question is when markets will recover, a first-pass answer is never.” Even though he has since recanted, we know what happened next, and how wrong he was. Political predictions generally are no better.

Hussman is an extreme and consistent example of a “gloom and doomer,” but he is hardly alone. Even though the last decade has seen stock prices march inexorably higher, fear is ever-present and drives many an apocalyptic prediction, if none quite so consistently dreadful as Hussman’s.

There always seems to be a bull market in bearish predictions – predictions that are often spectacularly wrong. Note the following huge errors during the bull market that has run, essentially unabated, for more than a decade.

- In 2010, noted economist Nouriel Roubini told CNBC that stocks were likely to continue their aggressive decline and shed another 20 percent in value as the world economy weakened. “From here on I see things getting worse.”

- In 2011, Gluskin Sheff economist David Rosenberg said another recession was coming, and soon, and that the S&P 500 would test the 1,000 level (it didn’t and is now well past 3,000).

- Also in 2011, Harry Dent predicted that the Dow would fall below 10,000 in the near term before crashing to around 3,000 in 2013, levels not seen since the early 1990s. Those levels still haven’t been seen, while the Dow approached 29,000 as 2019 ended.

- In 2012, the British economist Andrew Smithers asserted that “U.S. equities are 40 to 50 percent overpriced.”

- In 2013, Peter Schiff called for a crash that would blow the 2008-2009 financial crisis out of the water.

- In 2014, Henry Blodget expressed his expectation for a 40-55 percent crash.

- In 2015, then presidential candidate Donald Trump warned of a looming economic recession and a stock market bubble.

- In 2016, Paul Farrell of MarketWatch called for a 50 percent market crash: “a crash is a sure bet, it’s guaranteed certain.”

- In July of 2016, Jeffrey Gundlach, the chief executive of DoubleLine Capital, advised investors to “sell everything. Nothing here looks good.” He also said, “As sure as night follows day, passive is going out of favor.”

- Robert Kiyosaki, author of Rich Dad Poor Dad, predicted that we would witness the worst market crash in history in 2016: “we’re right on schedule.”

- In 2017, Marc Faber claimed that “We’re all on the Titanic.”

- Also in 2017, Jim Rogers, who formed the Quantum Fund with George Soros, said, “A $68 trillion ‘Biblical’ collapse is poised to wipe out millions of Americans” and “this is all going to end very, very, very badly.”

- In 2018, Scott Minerd, Chairman of Investments and Global Chief Investment Officer of Guggenheim Partners, forecasta 40 percent retracement. He saw the markets as being “on a collision course for disaster.”

- A year ago, Mark Yusko called for the immediate start of “one of the largest recessions we’ve ever had…There’s no stopping it.”

There are many other famous examples over the past decade than I could list, including terrible predictions from Stan Druckenmiller (“I couldn’t have been more wrong”), Carl Icahn, Howard Marks, Paul Singer, Bill Gross, George Soros, Rob Arnott, Tom Forester, Nafeez Ahmed, and Paul Tudor Jones, all really smart and accomplished investors.

There are current examples, too.

Traders today are buying hedges “like the world is about to end.” Warren Buffett hasn’t made an overt crash prediction. However, his Berkshire Hathaway cashed out over half of its investment portfolio last year. The $122 billion cash pile is unusual for Buffett, who typically puts his money to work through acquisitions, stock buybacks, or equity purchases. Michael Burry, made famous by The Big Short, is calling for a crash today on account of the popularity of passive investing, which he thinks has inflated security prices. “It will be ugly,” he says. Dennis Gartman, who’s shuttering his daily newsletter after 30 years, has some parting advice for investors: Go to cash.

As reported by The Wall Street Journal, Harry Dent, who has predicted booms and busts for decades with stunningly poor timing – for example, his forecast of a 17,000-point drop in the Dow in 2016, noted above — now predicts “a major financial crash and global upheaval that will dwarf the 2007-09 recession of the 2000s — and maybe even the Great Depression of the 1930s.”

For the past decade, the correlation between bearishness and losses has remained vanishingly close to 1.0. Unfortunately, nobody can predict (not remotely) when markets will correct or crash. It’s the three-body problem on steroids. Remember what Barton Biggs, Morgan Stanley’s former strategist, said: “Bullish and wrong and clients are angry; bearish and wrong and they fire you.” Accordingly, well over 95 percent of the money Hussman once managed – billions of dollars – has moved elsewhere. Hussman exemplifies the wisdom of legendary investor Peter Lynch, “Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.” The foresight of market strategists is more than a bit shaky, but their hindsight is always impressive.*

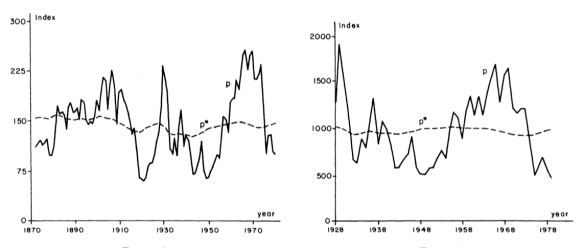

We should not expect ever to be able to identify the trigger of any correction or crash in advance or to be able to predict such an event with any degree of specificity. As Nobel laureate Robert Shiller clearly explained, “The U.S. stock market ups and downs over the past century have made virtually no sense ex post. It is curious how little known this simple fact is” (Shiller illustration below).

Thus, today could be the day that the market tanks…but you should not expect to see it coming.

Market forecasts have a long and ignominious history. Michael Batnick compiled year-end price targets from Wall Street’s alleged expert strategists going back to 2005 (2018; 2017; 2016; 2015; 2014; 2013; 2012; 2011; 2010; 2009; 2008; 2007; 2006; 2005) and found that out of the 153 price targets, only six called for lower prices. The average forecast was a nine percent gain which, not surprisingly, is right around the average annual return, even though the actual return is almost never average. In December 2007, shortly before the financial crisis, Barron’s wrote, “the dozen seers we’ve surveyed all have penciled in higher stock prices in 2008…On average, the group sees the Standard & Poor’s 500 at 1,640.” It closed the year at 865.58, nearly 50 percent lower. Economists overall have been wildly wrong about interest rates for more than a decade, consistently projected them to be much higher than they turned out to be.

Still, making market predictions is generally what Wall Street strategists do. It’s part of the gig. As the legendary investor Benjamin Graham wrote, “Nearly everyone interested in common stocks wants to be told by someone else what he thinks the market is going to do. The demand being there, it must be supplied.”

This past year’s set of strategist S&P 500 forecasts is much better than usual (most were positive), but still lousy. Because of course they are.

Strategist/Firm/S&P 500 prediction for 2019 year-end

Note: S&P 500 closed 2018 at 2,486; closed 2019 3,230.78

- Société Générale 2,400

- Francois Trahan UBS 2,550

- Lori Calvasina RBC 2,700

- Michael Wilson Morgan Stanley 2,750

- Barry Bannister Stifel Bannister 2,800

- Saira Malik Nuveen 2,840

- Rob Sharps Rowe Price 2,850

- Tobias Levkovich Citigroup 2,850

- Sean Darby Jefferies 2,900

- Darrell Cronk Wells Fargo 2,910

- Jonathan Golub Credit Suisse 2,925

- Savita Subramanian Bank of America Merrill Lynch 2,900

- Brad McMillan Commonwealth 2,950

- Tony Dwyer Canaccord Genuity 2,950

- John Stoltzfus Oppenheimer 2,960

- Sam Stovall CFRA 2,975

- John Praveen QMA 3,000

- PGIM 3,000

- LPL Research 3,000

- Hugo Ste-Marie Scotiabank 3,000

- David Kostin Goldman Sachs 3,000

- Kristina Hooper Invesco 3,000

- Maneesh Deshpande Barclays 3,000

- Dubravko Lakos-Bujas JPMorgan Chase 3,000

- Julian Emanuel BTIG 3,000

- Brian Belski BMO Capital 3,000

- Scott Wren Wells Fargo 3,030

- Chris Harvey Wells Fargo 3,079

- Ed Yardini Yardini Research 3,100

- Federated Investors 3,100

- John Normand JPMorgan Chase 3,100

- Noah Weisberger Sanford Bernstein 3,150

- Ben Laidler HSBC 3,150

- Thomas Lee Fundstrat 3,185

- Keith Parker UBS 3,200

- Binky Chadha Deutsche Bank 3,250

Not to be outdone, those making economic and bond market predictions were lousy too … lousier, even. Going into 2019, Federal Reserve officials expected economic conditions to support raising short-term interest rates twice. Instead, policy-makers lowered then three times. In the market for U.S. Treasury securities – where market participants set interest rates and where nearly everyone called for higher yields – rates fell even further from what were already historically low levels. The Wall Street Journal survey of 60 business, financial, and academic economists, one year ago, called for U.S. Treasury 10-year note yields at year-end 2019 to be 3.35 percent; they closed 2019 at 1.92 percent, 143 basis points lower. The universe of bond market forecasters couldn’t have been more wrong, for a decade and more.

Indeed, robust academic research has shown that flipping a coin is a more accurate predictor of the future than the forecasts of leading economists. A CXO Advisory Group study collected 6,582 forecasts for the U.S. stock market from 68 market commentators and found similarly that a coin flip was more accurate than the forecasters.

Before you make serious portfolio changes based upon some urgent warning, be sure you are well aware of the risks and opportunity costs of doing so…and make sure you know the full and complete track record of the forecaster upon which you are relying. Very few “expert” forecasters will talk about their misses. And they all have lots of misses.

It’s easier to sound smart when calling for a market correction. Moreover, we should all recall the insidious incentives supporting bold predictions, most notably potential fame, funding, and influence, especially because there seems to be no accountability for being wrong. Many big careers have been made by being right once in a row.

We seem to have a sort of psychological craving for apocalyptical thinking. As the mathematician Alfred Cowles observed decades ago, people “want to believe that somebody really knows.” Still, uncertainty, together with appropriate and legitimate concern, does not require panic. Dealing with it successfully does require planning, however.

As Warren Buffet reminds, “[f]orecasts usually tell us more of the forecaster than of the future.” Markets go up and markets go down, sometimes by a lot. At least one of these doomsday characters will eventually be right. But you should assume that any such rightness will be much more a function of luck than skill.

We’ve had more than a decade of generally great stock market performance. Change is gonna come.

Maybe sooner. Maybe latter. Maybe today. But when it happens will be utterly unrelated to any Wall Street (or other) forecast or prediction.

____________________

* “When Bloomberg contacted economists who signed an open letter in 2010 declaring that Ben Bernanke’s policies would produce runaway inflation to ask why the inflation never materialized, not one of them would admit having been wrong, because that would have meant admitting that their model of how the economy works was way off-base. Even hard science is plagued by the inability to admit error. The great physicist Max Planck famously declared that opponents of a new scientific truth are rarely persuaded – they just eventually die off. Students of business history talk about a phenomenon they call “escalation of commitment,” in which managers not only refuse to abandon failing strategies but dig in deeper, in an attempt to prove that they were right all along.”

Pingback: Opening Bell 03.01.2020 - StockViz

Pingback: Tim’s Top Links – 1/3/20 | Living With Money

Pingback: Friday links: lots of misses | AlltopCash.com

Pingback: Weekend reading: 2020 hindsight ⋆ The Passive Income Blogger

Pingback: These Are the Goods - The Irrelevant Investor

Pingback: These Are the Goods | Financial Chickens

Pingback: 10 Monday AM Reads | Share Market Pro

Pingback: Reasons to be fearful and cheerful in 2020 – The FIRE Shrink

Pingback: January 2020 Top Picks | FinTech Freedom

Pingback: February 2020 Top Picks | FinTech Freedom

Pingback: Nobody Really Knows | Above the Market