A Christian radio network called Family Radio began spreading “the word of God to the world” in 1958 in a mundane way, featuring hymns and conventional – albeit very conservative – Bible teaching. Despite many years of growth and financial health, founder and retired engineer Harold Camping became increasingly enamored with a personal brand of doomsday Bible prophecy suffused with numerology and eventually began pushing Family Radio toward that focus. After a more tentative prediction of 1988, the Berkeley-educated Camping thought that the world would end (he wasn’t absolutely certain, but was “more than 99 percent sure“) in September of 1994. He actively advocated that view on his popular daily, nationwide call-in show on the network in the months leading up to the predicted date.

Once September of 1994 had come and gone, things returned mostly to normal…for a while. However, Camping was still crunching numbers (to obtain “infallible, absolute proof”) and eventually decided that the correct date was May 21, 2011. He was really sure this time. First would come a massive earthquake, powerful enough to throw open all the world’s graves, followed by the heathen dying off until the end of the world in October. At Camping’s urging, Family Radio spent over $100 million (donated) dollars proclaiming Judgment Day to the masses over its roughly 140 stations and with billboards, fliers and more. The network’s website featured a “countdown clock” under the banner headline: “Judgment Day: the Bible guarantees it.”

Like far too many others, Peter Lombardi, a 44-year-old contractor from Jersey City, N.J., took an “indefinite break” from his work to warn others about this coming end. He plastered his Dodge minivan with stickers proclaiming the “awesome news” of Judgment Day and paraded through Manhattan to spread the word and hand out fliers.

When May 21, 2011 came and went, Camping went back to his studies and soon “clarified” that the May 21 date was “an invisible judgment day” he had come to understand as a spiritual, rather than physical event. The actual day of apocalypse would not be until October 21.

Camping was wrong yet again. On October 22, Peter Lombardi was peeling stickers off his minivan. Family Radio was trying to decide what to do next. Its website was not immediately updated and the countdown clock was stopped at zero and holding. Harold Camping was attempting to figure out what had gone wrong, saying he was “flabbergasted” and “looking for answers.”

After this final, humiliating failure, in a letter to followers some days later, Camping apologized for getting it wrong and acknowledged that he had “no new evidence pointing to another date for the end of the world” and “no interest in even considering another date.” However, he found a silver lining to the confusion, noting that his “incorrect and sinful statement allowed God to get the attention of a great many people who otherwise would not have paid attention.” So there’s that. Camping thereafter largely disappeared from the ministry he had founded – it became a shell of its former self – and died in 2013 at age 92.

Most end-times preachers do not make Camping’s mistake of offering a date certain. The cynical might suggest that offering specificity puts a sell-by date on both relevancy and donations. Yet there is a solid Biblical reason why preachers insist that it is not possible to know when Jesus will return. “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, but only the Father” (Matthew 24:36). What end-times preachers of every period and every ilk all agree on with unalterable conviction is a carefully crafted loophole. They insist that it is possible to know the season – if not the date – of the Lord’s return and that they are surely living in that season (I have never heard anyone try to define the length of “season”).

Most end-times preachers do not make Camping’s mistake of offering a date certain. The cynical might suggest that offering specificity puts a sell-by date on both relevancy and donations. Yet there is a solid Biblical reason why preachers insist that it is not possible to know when Jesus will return. “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, but only the Father” (Matthew 24:36). What end-times preachers of every period and every ilk all agree on with unalterable conviction is a carefully crafted loophole. They insist that it is possible to know the season – if not the date – of the Lord’s return and that they are surely living in that season (I have never heard anyone try to define the length of “season”).

For a surprising number of people, it is perpetually the end-times. The apocalypse is always nigh.

I grew up in that culture, with its preachers reading with “the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other” for hints of the coming Rapture. The faithful feasted on prophecy conferences, huge and colorful charts explaining the book of Revelation (the “Apocalypse of John”) and the end of the age, recitations of the acts of multiple evildoers in the end-times saga from the Russians to the Tri-Lateral Commission, and detailed explanations why Henry Kissinger was the Antichrist. They were (and are) too often led by men who cast themselves as heroes in the story, proclaiming Truth to power, yet are so outraged at the state of the world that they anxiously pray for God to blow it to smithereens. It was (and is) always the Last Days. As a youngster, if I returned home to an unexpectedly empty house, I feared that the Rapture had come and I had been “left behind.”

This “end-times” focus was hardly new when I was young and did not die with Harold Camping. It continues unabashed and unabated, with adjustments for changing times and circumstances. When I was a kid, the most popular end-times “expert” was Hal Lindsey, who in 1970 published The Late, Great Planet Earth, which has sold over 35 million copies and predicted that the Rapture would come any day now for nearly five decades. Obviously, the book has been “updated” many times since. A movie of it, narrated by Orson Welles, came out in 1979 (see below). Donations are still accepted at 1-800-RAPTURE (really).

The list of apocalyptic preachers is a long and ignominious one, stretching back more than 20 centuries and continuing today. Examples in my lifetime include mega-church pastor Chuck Smith, who predicted Jesus would return “before the end of 1981,” and Pat Robertson, who offered a rock-solid “guarantee” that the end of the world was coming in the fall of 1982. A more recent example is the Left Behind series of novels, which have sold over 65 million copies.

Since World War II, most prophecy preachers have focused on the “signs of the times” (Matthew 16, not Harry Styles) that illustrate a prophetic jigsaw puzzle of apocalyptic events that fulfill the prophecies of the Bible, mostly in Revelation. These signs typically include the 1948 creation of Israel, the 1967 recovery of Jerusalem, the rise of Russia (seen as Magog, from Ezekiel, a “land in the far north” that comes to attack Israel), an Arab world poised against Israel, the apostasy of Christian churches, and any move toward a one-world religion or government. Various potential antichrists have been proffered, including Kissinger, Mikhail Gorbachev, any then-current pope, and Barack Obama.

I have hypothesized that Barney the dinosaur might be the antichrist. If you write “cute purple dinosaur” in ancient Latin characters it becomes “CVTE PVRPLE DINOSAVR.” Extract the Roman numbers, add all those numerals together [C+V+V+L+D+I+V], and the result is 666, the “number of the beast” (Rev. 13:18; not Iron Maiden). The recent news that a Wisconsin technology company is offering its employees microchip implants in their hands to be used to scan into work and purchase food there has provided great fodder to prophecy affectionados thinking about the “mark of the beast” (Rev. 13:16-17). We always live in the shadow of the apocalypse.

I have hypothesized that Barney the dinosaur might be the antichrist. If you write “cute purple dinosaur” in ancient Latin characters it becomes “CVTE PVRPLE DINOSAVR.” Extract the Roman numbers, add all those numerals together [C+V+V+L+D+I+V], and the result is 666, the “number of the beast” (Rev. 13:18; not Iron Maiden). The recent news that a Wisconsin technology company is offering its employees microchip implants in their hands to be used to scan into work and purchase food there has provided great fodder to prophecy affectionados thinking about the “mark of the beast” (Rev. 13:16-17). We always live in the shadow of the apocalypse.

The religious are far from the only people who are fascinated and seduced by apocalyptic themes and narratives. We are all natural-born and equal opportunity extremists who want to live in exceptional times. That is why, for example, in the financial world, we regularly overpay both for insurance and for lottery tickets (literal and figurative). We are pulled toward extremism by our inherent biases, including tribalism, herding, excessive certainty and overconfidence. The problems caused by these biases are compounded by our ideological nature, our propensity for confirming what we already believe and our general inability to see that which disconfirms it. The sad truth is that none of us is as good as we think we are. We postulate apocalyptic conclusions irrespective of whether there is good support for them. Evidence of this obsession abounds.

Culture

Culture, popular and otherwise is awash in the apocalyptic. Art, movies, sci-fi, dystopian literature, comic books, graphic novels, television, radio, and even literary fiction employ such themes and narratives extensively – don’t get me started on the internet. The media loves its disasters, the bigger the better, which (of course) provide great ratings. We humans are attracted to doom, boom and gloom like moths to a flame.

Indeed, throughout much of popular culture, it always seems to be the end times. The warring kingdoms of Westeros refuse to recognize the threat of the White Walkers. The authorities will not take action before the contagion has time to spread. The monsters who walk among us and threaten us are our fellow human beings; soon enough, we will all be monsters, too. James Bond may stop the evil Blofeld and superheroes may always save the world, but sometimes the apocalypse is all too real. Sometimes the world ends with a bang; sometimes with a whimper (with apologies to T.S. Eliot). Apocalyptic imagery seems to be increasing and evolving. The apocalypse has never come (it hasn’t yet, anyway, or at least not entirely), but it is always with us. We are transfixed by and permeated with doom.

Politics

Politics also lives and breathes doomsday scenarios. Every election is the most important of our time and cast as a morality tale with the fate of the world hanging in the balance. Every favored candidate is necessary to stave off annihilation. Every opponent is the antichrist, at least figuratively.

For example, President Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, is convinced that the apocalypse is coming and war is inevitable. Turnabout is fair play, of course, and members of the Democratic party and the mainstream media tell us pretty much all day every day that President Trump is the antichrist incarnate. Indeed, Mr. Trump single-handedly inspired the scientists who manage the “Doomsday Clock” to move it to within two-and-one-half minutes of midnight, the closest it has been since 1953. Trump advocate and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones of Infowars provides predictions of the apocalypse on an almost daily basis.

Most noteworthy to me (since these are my people), is the way the vast majority of (often religious) conservatives raced to support Mr. Trump, after having spent decades extolling the need for our leaders to be identified with personal integrity. Our president is, without plausible objection, a disgraced, disloyal huckster, draft-dodger, bankrupt casino-owner, porn actor (as himself, of course), conspicuous consumer and lover of money. He is a thrice-married, cursing, serial adulterer, sexual predator, habitual liar and vulgarian with no apparent moral, intellectual or political center, famous for unethical business practices, who is largely uninterested in typical Republican policy positions and who is consistently vindictive, impulsive and short-sighted. Personal character is hardly his strong suit. Yet religious conservatives support him vigorously, more strongly than other recent Republicans. Even his style – “flamboyant and vaudevillian” – does not fit. They supported him, they say, because they saw 2016 as a “Flight 93 election.” Hillary Clinton was portrayed not just as deeply flawed and dangerous. She was portrayed as an existential threat.

Thus, even conservatives with no love for Mr. Trump decided that because the end of the world was at hand, they needed to charge the cockpit or die. They may have died anyway, of course, and if anyone reached the cockpit, there was no particular reason to expect that the plane could be brought down safely (as the national news demonstrates on a daily basis). Yet they felt obligated to try. “There are no guarantees. Except one: If you don’t try, death is certain. To compound the metaphor: a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances.” I would have thought it impossible to read the portentous “Flight 93” essay without thinking that its advocates were at least a bit unhinged. Silly me. Jim DeMint (to pick one example among many), then head of The Heritage Foundation, opined that, “What just happened, in this election, may have preserved our constitutional republic.”

I want to be careful not to seem to paint with too broad a brush. To be clear, I can imagine reasonable conservatives deciding that Mr. Trump was a lesser evil than Ms. Clinton on matters of policy. I could not vote for the former Secretary of State either. I can imagine reasonable people deciding that particular issues (the Supreme Court, for example) are sufficiently important to justify a Trump vote. But I have been consistently struck by how quickly and readily otherwise principled people who advocated for decades that personal character was crucial in a president so readily gave that principle up – and forever gave up with it the ability unhypocritically to claim that character counts – for the opportunity to stand in proximity to political power. That point is especially poignant because the moral high ground was eagerly surrendered when virtually no one thought Mr. Trump had even a remote chance of winning. The threatened apocalypse was the justification offered and accepted for doing so.

Science

The world we live in is profoundly complex and is much more difficult for us to navigate than we usually think or assume. According to Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, “[w]e systematically underestimate the amount of uncertainty to which we’re exposed, and we are wired to underestimate the amount of uncertainty to which we are exposed.” Accordingly, “we create an illusion of the world that is much more orderly than it actually is.” It is that illusion to causes many mistaken conclusions, conclusions we (and even scientists) hold onto far too long.

Perhaps worse, when (even) scientific views are held with religious fervor and the lack of appropriate skepticism, they run a much greater risk of error. As Frank Bruni, quoting Jonathan Haidt in The New York Times, noted, “’When something becomes a religion, we don’t choose the actions that are most likely to solve the problem,’ said Haidt, the author of the 2012 best seller The Righteous Mind and a professor at New York University. ‘We do the things that are the most ritually satisfying.’”

It is axiomatic that the more strongly someone is convinced of something, the harder it is to change his or her mind. Accordingly, scientists – despite their ostensible commitment to the idea that new or better evidence can always suggest a different conclusion – are as prone to holding on to a mistaken view as any ideologue. Their determination that their interpretation of the evidence is objectively established (together with standard issue optimism bias, confirmation bias and the like) can make them as hardened against reality as any other zealot. As the great physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman stressed, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.”

With that important predicate, consider just a small subset of science’s own apocalyptic literature, some of it actually reality-based, and much of it all too current. According to some remarkable geological evidence, an asteroid roughly six miles in width collided with our Earth about 65 million years ago. The impact created a huge explosion and a crater more than 100 miles wide. Debris from the explosion was catapulted into the atmosphere, severely altering the climate, and leading to the extinction of most of species that existed at that time, including the dinosaurs.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring described in powerful detail the consequences of ecological degradation. Carson shone a light on poisons from insecticides, weed killers, and other common products as well as the use of sprays in agriculture and how they impacted human lives and the environment. It led to real action – most prominently the banning of DDT – and is perhaps the founding document of the environmental movement.

January 1, 2000 was supposed to prove, once and for all, that the Luddites were right. Technology would bring the world crashing down. Many analysts forecast that when the calendar rolled from 1999 to 2000 (“Y2K”), entire computer networks would crash, causing widespread dysfunction for a global population that had become utterly dependent on computer technology. The alleged problem was that many computers had been programmed to record dates using only the last two digits of every year, meaning that the year 2000 would register as the year 1900, totally screwing things up. However, by time the last chords of Old Lang Syne had drifted away, it was clear that all the fuss had been much ado about nothing. The apocalyptic predictions were false.

Michael Lewis’s recent Vanity Fair piece compellingly shows that the ineptitude, disinterest, lack of understanding and willful ignorance by the Trump administration about the role of the Department of Energy, from our nuclear arsenal to the electrical grid, is perhaps as scary as any external threat. After all, the DOE is “a powerful tool for dealing with the most alarming risks facing humanity.” Risk management is inherently related to science and the proposed Trump budget is largely designed to eliminate government science and leave all such efforts to private industry irrespective of whether private industry is willing or able to take up the challenge.

Last month, New York magazine published its most-read article ever, a piece of extinction porn entitled “The Uninhabitable Earth” about the world ending due to climate change. Note the opening sentence: “It is, I promise, worse than you think.” The opening section is headlined as “Doomsday,” with later sections covering such uplifting topics as “Heat Death,” “The End of Food,” “Climate Plagues,” “Unbreathable Air,” “Perpetual War,” “Permanent Economic Collapse,” and “Poisoned Oceans.” Scientific American has speculated on several other ways that the world as we know it might end. It seems as though the end is always near.

Kathryn Schultz won a Pulitzer Prize for her 2015 piece in The New Yorker, “an elegant scientific narrative of the rupturing of the Cascadia fault line, a masterwork of environmental reporting and writing.” Schulz reported that we are overdue for a mega-quake that arrives every few hundred years or so along the Washington coast that will likely cause the worst natural disaster in North American history. She also details our woeful lack of preparedness for such a quake and quotes a FEMA official who said the agency operates under the assumption that everything west of Interstate 5 in the Pacific Northwest would be “toast” following the quake’s resulting tsunami.

However, Schultz is careful to point out that the next such “big one” could be hundreds of years away. That is a crucial point because, even in science, when analysis moves to forecasting – like human forecasting generally – it is not usually any good. The universe and its component parts are far too complicated and nonlinear to offer ready predictability. In other words, the world is far messier and less predictable than we think and desperately want to believe. We always know less than we think and assume. Information is cheap; meaning is expensive.

Even when performing careful analytical, evidence-based work, we are and remain biased, ideological and inherently tribal, as noted above. For example, alleged scientific authorities have predicted the end of the world and civilization as we know them at the hand of pandemics, environmental catastrophes and otherwise over and over again. Yet we are still here, at least for now, in defiance of Thomas Malthus’s eighteenth-century warnings about overpopulation and ecologist Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 prophesy (with proposed authoritarian solutions) in The Population Bomb that “[i]n the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.”

Despite the clarity and specificity of both his predictions and his errors, Ehrlich went on to compound his mistakes by trying to deny that they were really errors. The Stanford biologist and MacArthur Fellow sounded like a foolish market analyst insisting he was right but early when he asserted, “[o]ne of the things that people don’t understand is that timing to an ecologist is very, very different from timing to an average person.”

Ehrlich’s view, essentially, is that the human population was too big and would quickly strip the world of resources, leading to mass starvation. His forecasting failure was predicated, at least in part, on his knowledge and analysis having insufficient breadth – which should not be too surprising given the breadth of the universe. The late economist Julian Simon argued that what Ehrlich missed is the robustness of the market economy. As a useful resource becomes rare, it becomes more expensive, and that higher price incentivizes exploration (to find more) and/or innovation (to create an alternative).

In 1980, Simon publicly challenged Ehrlich to a bet, and Ehrlich accepted. Ehrlich selected five raw minerals — chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten — and noted how much of each he could buy for $200. If his prediction was right and resources were growing scarce, in ten years the minerals should become more expensive; if Simon was correct, they should cost less. The loser would pay the difference. In October 1990, ten years later, Simon received a check in the mail from Ehrlich for $576.07. Each of the five minerals had declined in price. Simon and his faith in the market were victorious. “The market is ideally suited to address issues of scarcity,” said Paul Sabin, a Yale environmental historian. “There’s often cycles of abundance and scarcity that are in dynamic relationship with each other where one produces the other.”

The idea that the world is better than it was and can get better still fell out of favor among a certain academic class long ago. In The Idea of Decline in Western History, for example, the Smithsonian’s Arthur Herman argues that prophets of doom are central to the liberal arts curriculum: Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer, Martin Heidegger, Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Jean-Paul Sartre, Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault, Edward Said, Cornel West, and the eco-pessimists noted above. Herman laments a “grand recessional” of “the luminous exponents” of Enlightenment humanism, the ones who believed that “since people generate conflicts and problems in society, they can also resolve them.” In History of the Idea of Progress, the late sociologist Robert Nisbet of Columbia made a similar point. “The skepticism regarding Western progress that was once confined to a very small number of intellectuals in the 19th century has grown and spread to not merely the large majority of intellectuals in this final quarter of the century, but to many millions of other people in the West.”

To be sure, I take climate change and other potential environmental calamities most seriously indeed, but the odds are strongly against our ever having everything (and especially future events) all figured out with great specificity, much less soon. Moreover, we should all recall the insidious incentives supporting bold predictions, most notably potential fame, funding and influence, especially because there seems to be no accountability for being wrong. The list of alleged scientific “facts” that turned out not to be is a distressingly long one.

As I have argued repeatedly, on our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, assertive truth-tellers. However, on most days, all too much of the time, we are delusional, lazy, partisan, arrogant confabulators (even the best rationalists among us). This problem manifests itself in our attempts as a society to try to cut through the projections of doom to deal effectively with very real risks and problems we face, environmental and otherwise.

The Yellowstone Caldera

Among my favorite doomsday predictions are those relating to the great Yellowstone Caldera volcano, which is often described as about ready to blow and destined to create terror and mayhem. Those claims persist even though Yellowstone is relatively calm as giant caldera systems go. Montana suffered its worst earthquake in 34 years last month and many people freaked out, even though it had nothing to do with the caldera. As a good example of the genre (another here), check out the following headline from The Toronto Sun on March 9, 2014.

The prose within the body of the article is more than a bit apocalyptic too.

Scientists have discovered Yellowstone National Park supervolcano is two-and-a-half times larger than previously thought, and it could erupt with 2,000 times the force of Mount St. Helens — a blast that would devastate North America and dump more than 10 cm of ash on Western Canada alone.

The national park and surrounding communities would be annihilated, while plants and entire farms hundreds of kilometres away would be wiped out. Escape would be futile — ash damages commercial aircraft engines, making flight hazardous.

Sulfur entering the upper atmosphere would turn to sulfur dioxide, circle the globe and drop temperatures. Worldwide famine would likely ensue.

Finally, toward the end of the article a bit of qualification is offered. “The chance per year of Yellowstone blowing up — they’re low…. But it’s potentially going to happen sooner or later.” The headline is the takeaway (and terrific click bait too).

Volcanologist Erik Klemetti of Denison University has written an outstanding piece (more here and here) outlining how to examine volcano doomsday predictions. He proposes four simple steps, each of which is applicable to threatened major volcanic eruptions, major market crash predictions and to just about any sort of analytical construct.

- Consider your source. Unless the source is unimpeachable and the underlying facts well supported, ignore it.

Experts (good and bad, real and phony) are all prone to the same weaknesses all of us are. Philip Tetlock’s excellent Expert Political Judgment examines why experts are so often wrong in sometimes excruciating detail. Even worse, when wrong, experts are rarely held accountable and rarely admit it. They insist that they were just off on timing (“I was right but early”), or blindsided by an impossible-to-predict event, or almost right, or wrong for the right reasons. Tetlock even goes so far as to show that the better known and more frequently quoted experts are, the less reliable their guesses about the future are likely to be (think Jim Cramer), largely due to overconfidence, another of our consistent problems.

Many of the biggest and smartest investors in the world were highly negative on the stock market in 2016. We heard negative equity calls from Stan Druckenmiller (net worth, $4.4 billion) (“Get out of the stock market”), Carl Icahn (net worth, $17.4 billion)(“I don’t think you can have [near] zero interest rates for much longer without having these bubbles explode on you”), Jeff Gundlach (net worth, $1.4 billion)(“[S]ell everything. Nothing here looks good”), Howard Marks (net worth, $1.9 billion), Paul Singer (net worth, $2.2 billion)(“I think it’s a very dangerous time in the financial markets”) and Bill Gross (net worth, $2.4 billion)(“I don’t like bonds; I don’t like most stocks; I don’t like private equity”).

Famous hedge fund manager George Soros (net worth, $24.9 billion) doubled down on his bet against the S&P 500, buying put options on just over 1.9 million shares the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) so that he owned puts on just over 4 million shares. It was his fund’s biggest holding according to his 13-F filing. Similarly, global macro hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones (net worth, $4.7 billion) doubled-down on his bet against the stock market, according to his fund’s 13-F filing. During the second quarter, he bought put options on over 5.95 million shares of SPY so that the fund owned puts on 8.34 million shares of the ETF, making it that fund’s largest position too. In less reputable territory, Robert Kiyosaki, author of the “Rich Dad” series of popular personal-finance books, predicted that 2016 would bring about the worst market crash in history. So did Paul Farrell.

Despite these dire – even apocalyptic – warnings, for the calendar year 2016, the S&P 500 provided a total return of 11.74 percent.

My favorites among the extreme naysayers are Harry Dent, Marc Faber and John Hussman, each of whom has been calling for a market crash repeatedly since 2010 or so, with total confidence, despite the consistency of healthy market performance. Eventually they will be right, of course – even a stopped clock is right twice a day. In the interim, however, those who followed their “advice” have suffered mightily. Dent no longer runs money (his funds closed due to poor performance) and Faber works predominantly in frontier markets, so they are generally insulated from the consequences of their being wrong so consistently.

Hussman is not. His flagship Hussman Strategic Growth Fund’s one, three, five and ten-year average annual returns, through June 2017, are -15.53 percent, -11.34 percent, -9.54 percent and -6.03 percent. Ouch. Remember what Barton Biggs, Morgan Stanley’s former strategist, said: “Bullish and wrong and clients are angry; bearish and wrong and they fire you.” Accordingly, well over 90 percent of the money Hussman once managed – billions of dollars – has moved elsewhere. Hussman exemplifies the wisdom of legendary investor Peter Lynch, “Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.”

We should not expect ever to be able to identify the trigger of any correction or crash in advance or to be able to predict such an event with any degree of specificity. As Nobel laureate Robert Shiller clearly explained, “The U.S. stock market ups and downs over the past century have made virtually no sense ex post. It is curious how little known this simple fact is.” Thus, today could be the day that the market tanks…but you should not expect to see it coming.

While I would love to find at least a few, there is little reason to think that anybody can predict major market movements with any degree of consistency (if readers have candidates to offer I would love to be so informed). There is no reason to think that some guy on the internet can. Before you make serious portfolio changes based upon some urgent warning, be sure you are well aware of the risks and opportunity costs of doing so…and make sure you know the full and complete track record of the forecaster upon which you are relying. Very few “expert” forecasters will talk about their misses and they all have lots of misses.

- Consider the data. Demand lots of data from multiple sources and with careful confirmation.

Market crashes happen. When the next one comes along — and it surely will, perhaps today, perhaps years from now — some number of people will seem to have presciently predicted it. Many more will try to take credit for having done so. Still, since such major catastrophic events do not happen all that often and since there does not seem to be any good reason to think that any particular person will have it right, acting on such predictions is dangerous business indeed.

Market crashes happen. When the next one comes along — and it surely will, perhaps today, perhaps years from now — some number of people will seem to have presciently predicted it. Many more will try to take credit for having done so. Still, since such major catastrophic events do not happen all that often and since there does not seem to be any good reason to think that any particular person will have it right, acting on such predictions is dangerous business indeed.

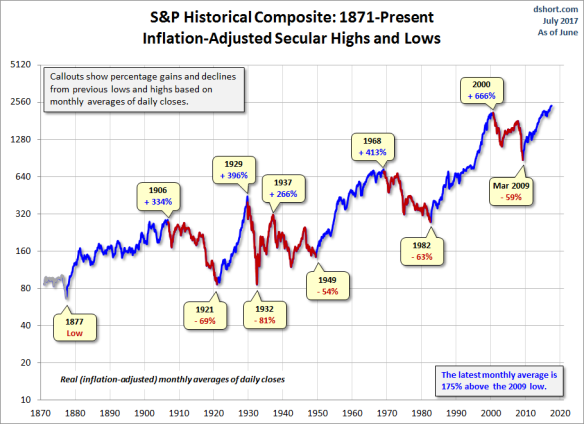

That’s largely because big crashes (as opposed to corrections — which are common) don’t happen all that often. The worst one-day market loss occurred on Black Monday, October 19, 1987, when the Dow lost over 22 percent of its value. The biggest one-day loss in 2008 was 7.87 percent; in 2001 it was 7.13 percent. Over longer periods there have been four secular bear markets (see below, from Doug Short) when peak-to-valley losses were much greater.

The standard crash warning article does not specify whether a one-day or longer-term trend is predicted. Specificity is, of course, a great enemy of media pundits and predictions. One who keeps predicting doom without specificity will eventually be right, no matter how much opportunity cost has been paid in the meantime.

- Consider the scale of things. Even if there is really good evidence of a current problem, most such problems are relatively minor, and even the major problems are rarely catastrophic.

As noted above, corrections are commonplace (see below, from MarketWatch).

So if you own stocks and are terrified by the prospect of a correction — standard market volatility — you need to re-think your entire investment philosophy and dramatically reduce your return (and perhaps lifestyle) expectations accordingly. Despite corrections, the S&P 500 has provided average annual returns of 11.42 percent from 1928-2016, far, far more than other alternatives. As John Bogle expressed it, “If you have trouble imagining a 20 percent loss in the stock market, you shouldn’t be in stocks.”

- Consider the motivation. Does the forecaster have personal motivation for making the prediction?

Consider the people touting imminent doom. Most are selling something, have a political motivation for wanting what they are forecasting, or both (for example, Alex Jones sells overpriced “solutions” to the conspiracy theories he promulgates). All are looking to make a name for themselves by getting a big call right. There is a wide body of research on what has come to be known as “motivated reasoning” and – more recognizably for those of us in the investment world – its “flip-side,” confirmation bias. While confirmation bias is our tendency to notice and accept that which fits within our preconceived notions and beliefs, motivated reasoning is our complementary tendency to scrutinize ideas more critically when we disagree with them than when we agree. We are also much more likely to recall supporting rather than opposing evidence. It is why we concoct silly conspiracy theories, for example. In general, we see what we want to see and act accordingly. And if it’s in our interest to see things a certain way, we almost surely will. Upton Sinclair offered perhaps its most popular expression: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

Klemetti’s helpful analysis focuses upon spotting bad forecasts of doom. We should also pay attention to what might improve our forecasts and consider whether the forecasts we see were based upon best practices. These best practices were the goal of Philip Tetlock’s book, Superforecasting, based upon Tetlock’s intense, long-term study of forecasts and forecasters. The central lessons of Superforecasting can be distilled into a handful of directives, all consistent with Klemetti’s argument. Base predictions on data and logic, and try to eliminate personal bias. Working in teams helps. Keep track of records so that you know how accurate (or inaccurate) you (and others) are. Think in terms of probabilities and recognize that everything is uncertain. Unpack a question into its component parts, distinguishing between what is known and unknown, and scrutinizing your assumptions. Recognize that the further out the prediction is designed to go and the more specific it is, the less accurate it can be.

In other words, we need rigorous empiricism, probabilistic critical thinking, a recognition that absolute answers are extremely rare, regular reassessment, accountability and an avoidance of too much precision. Or, more fundamentally, we need more humility and more diversity among those contributing to decisions. We need to be concerned more with process and improving our processes than in outcomes, important though they are. “What you think is much less important than how you think,” says Tetlock. Superforecasters regard their views “as hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be guarded.” As Tetlock told Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal, most people “are too quick to make up their minds and too slow to change them.”

Most importantly, perhaps, Tetlock encourages us to hunt and to keep hunting for evidence and reasons that might contradict our views and to change our minds as often and as readily as the evidence suggests. One “superforecaster” went so far as to write a software program that sorted his sources of news and opinion by ideology, topic and geographic origin, then told him what to read next in order to get the most diverse points of view.

The best forecasters are all curious, humble, self-critical, give weight to multiple perspectives and feel free to change their minds often. In other words, they are not (using Isaiah Berlin’s iconic description, harkening back to Archilochus), “hedgehogs,” who explain the world in terms of one big unified theory, but rather “foxes,” who, Tetlock explains, “are skeptical of grand schemes” and “diffident about their own forecasting prowess.”

Pretty much the only forecast that is almost certain to be correct is that market forecasts are almost certain to be wrong. We’d all be wise to recall Warren Buffett’s admonishment to ignore all forecasts because they tell you nothing about where the market is going.

Recent Headlines

Today’s headlines, as ever, offer plenty of apocalyptic forecasts. A few examples follow. Note that most of the forecasters are really well-regarded – they are not cranks (with a couple of exceptions).

Tom Forester has already predicted one stock downturn. Before the 2008 market collapse, Forester sold off enough bank stocks to bring his fund’s financial holdings down to one-quarter of his benchmark’s financial holdings. Institutional Investor highlighted his fund as “the sole long-only mutual fund in the U.S. to gain in 2008.” He is similarly concerned today. “The next time we see a bear market, it’s going to be agonizing,” Forester says. “There won’t be anywhere to hide on the way down.” He says the problem is valuation.

“Some stocks in America are turning into a bubble, the bubble is going to come, and then it’s going to collapse,” Jim Rogers (who founded Quantum Fund with George Soros) told Business Insider on its show “The Bottom Line.” Rogers warns, “You should be very worried.” He says the problem is debt.

The great Howard Marks, who wrote “bubble.com” just before the tech bubble burst in 2000 and “The Race to the Bottom” in February of 2007, ahead of the mortgage crisis, is really worried again. “I’m convinced ‘they’ are at it again – engaging in willing risk-taking, funding risky deals and creating risky market conditions.” Of course, Mr. Marks has been cautious since 2011. He says the problem is indiscriminate buying.

Marc Faber is famous for always preparing for a stock apocalypse. Always. All the time. He’s pretty much a joke, but he is currently calling for a 50 percent collapse. He says the problem is margin debt and markets being driven by too few companies.

On the other hand, Warren Buffett is sitting on an enormous wad of cash (nearing $100 billion). He thinks the problem is that prices are too high (because of course he does).

“Don’t be mesmerized by the blue skies,” Bill Gross, the well-known bond investor, formerly known as the “Bond King,” said in his June investment outlook letter. “All markets are increasingly at risk.” He thinks the problem is a lack of real productivity.

Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates is scared of the markets too. “In the United States, there’s not enough fear,” Arnott says. “There’s a sense that the risks are not there.” A shift could come at any moment, he adds. “Markets move with the changes in perception,” Arnott adds. “One bad thing could cause a downturn,” and we may be due for that one bad thing, he cautions. “It’s hard to paint a rosy picture for any long-term investor. The market is just too expensive,” Arnott says. “At any point it might roll over and die.” According to Arnott, therefore, the problem is that investors are devoid of necessary caution.

Nafeez Ahmed isn’t too worried about 2017. But look out thereafter. Ahmed says that a coming oil crunch will lead to an oil, food and financial crash in 2018.

All are calling for a market collapse, but their reasoning diverges widely. The proposed reasons – valuations, debt, indiscriminate buying, margin debt, a top-heavy market, a lack of productivity, excessive confidence and an oil crunch – are often connected but don’t remotely create a comprehensive and coherent whole. They may be right, of course, but there is little reason to expect that any of them would be right for the right reasons. That should give any of us pause before putting too much faith in any of these doomsayers, no matter how brilliant and successful they are.

Klemetti’s careful warnings and this lack of consensus do not mean we should do nothing in response to perceived dangers. While none of us has an edge that would allow us reliably to predict what the market will do in the near-term, we can plan for those inevitable downturns. In essence, we should use a diagnostic rather than a predictive framework. Diagnosing potentially problematic trends can help us to think in terms of probabilities, scenarios and a wider range of outcomes. Truly being a long-term investor is difficult because the long-term feels like an eternity in the moment. As Daniel Kahneman has explained, “the long-term is not where life is lived.”

As Klemetti advises, our responses should be fact-based and appropriately measured. There are multiple good examples of such approaches in the investment world. When times and markets are good – and they have been very, very good for nearly nine years – it is easy to become complacent. We can over-allocate to markets and sectors that are doing especially well. We can neglect rebalancing. We can expect the good times to continue indefinitely. We can continue to play after we have won the game. As the economist Hyman Minsky warned, however, the longer a financial cycle goes on, the more likely it is to turn to excess and end badly. That is why discipline is so important. If your portfolio is over-allocated to equities, consider your portfolio allocations. Rebalancing works.

Moreover, even the strongest buy-and-hold advocates should be willing to adjust their asset allocations in the face of changing market valuations. Sell off a few percentage points of a particular asset class when its future return expectations are low. This strategy, involving small and infrequent policy changes opposite large market moves (as we have seen for nearly nine years now), is a step-up from normal rebalancing – not just pruning the over-performing asset to a target allocation, but cutting it back still more in a maneuver William Bernstein calls “overbalancing.”

Diversification is vital in this context as well. It is valuable precisely because we do not know what the future holds. It allows us to be vaguely or even generally right rather than precisely wrong. If you are not well diversified and something goes wrong, the result can be devastating. Bernstein provides a nice summary. “First and foremost, don’t even think about trying to extrapolate macroeconomic, demographic, and political events into an investment strategy. Say to yourself every day, ‘I cannot predict the future, therefore I diversify.'”

As Michael Lewis has emphasized, “the human imagination is a poor tool for judging risk. People are quite good at responding to the crisis that just happened, as they naturally imagine that whatever just happened is most likely to happen again. They are less good at imagining a crisis before it happens—and taking action to prevent it.” Risks that are the most easily imagined are not the most probable. It isn’t the things you think of when you try to think of bad things happening that got you killed, “It is the less detectable, systemic risks.” Another way of putting it: “The risk we should most fear is not the risk we easily imagine. It is the risk that we don’t.”

The next time you see some pundit warning of yet another imminent crash, use Klemetti’s analytical framework to test how likely you think it might be that the pundit is correct and act accordingly. Klemetti’s conclusion is an important one (emphasis in original). “Once you’ve moved through these 4 steps, you’ll find that 99.9 percent of all Yellowstone eruptions rumors are untrue, and you can go back to your normal life. Spread the word to your friends, co-workers and family: Don’t let the purveyors of misinformation send you down the path to panic. Instead, stand up to them and use reason and science to turn them away!”

Market crashes occur more frequently than major seismic events at Yellowstone, but they still aren’t nearly as common as they are commonly predicted. So the next time you see an article about Yellowstone predicting impending doom remember that calderas are busy places and the media loves its disasters. There is probably no reason to get too worked up. Similarly, the next time you see someone predicting a major market crash, remember that markets are wildly busy places and the media loves its disasters there too. As do we all.

“There are only two kinds of forecasters: Those who don’t know and those who don’t know that they don’t know.”

John Kenneth Galbraith

Well now, Seawright, THAT was quite the essay. And look at all those wonderful links. I’ll be busy with this one for quite some time, and it was most generous of you to put it up here. Real Clear Markets might as well have queued it up at Real Clear Religion also. It is pleasing to discover one of “my people” out there in recovery (nearly 30 years for me). We could form a new group, you and I. We could call it Apocalyptics Anonymous. Think of all the people we might help.

I disagree with you on one thing, though. I don’t believe most people are by nature extremists and ideologues, otherwise the true believers wouldn’t need to expend so much time, effort and cash trying to convince the rest of humanity to join them. There is a continuum of experience. The worst cases on the continuum, without offense meant to their followers or the founders, are the founders of the religions, movements, and manias themselves. And even among them there are gradations of extremity. A St. Paul comes along and softens the apocalypticism of Jesus and John the Baptist, for example. A nuclear weapon did an awful thing 72 years ago yesterday, but Hiroshima has been rebuilt and Japan is an outpost of the free world today, so the fear mongers can move the hands on some Doomsday Clock all they want but the world didn’t end because one nuke was used, and it won’t end if one is used again (I’m not advocating this). Note that some of the guys who built the damn thing in the first place also feared before its first test that it might create a chain reaction in the atmosphere and blow the whole place to kingdom come. And Oppenheimer himself famously intoned “I am become death, the Destroyer of worlds”. But most of us are still here, with the notable exception of some people at the other end of the continuum who throw caution to the wind and win Darwin Awards. Somewhere in the middle is the proper caution and the proper carelessness.

And there’s the nut of it, I think, inordinate fear of death, debilitating preoccupation with death. The Doom Peddlers aren’t really wrong, they’re early, projecting death onto reality before the time. They are hard-wired to “prolepsis”, the representation of a thing as existing before it actually does. Meanwhile there is reality as it actually exists.

On the mundane level of markets, which is what brings readers here, I think representing how things actually are is the most important thing to grasp when thinking about the future. For me, that means thinking about what this time has really been like since August 2000, and more importantly, what it has not been like. It has not been like the Reagan bull market, which gave us almost 19% per annum average annual return from the S&P 500 for 18.1 years. Through June 2017, on the other hand, the average return has been just shy of 5% per annum. That is nearly 17 years of the bill of goods the optimists sold us, pointing to the Reagan bull.

But I’m not angry anymore. I’ve come to think of it as mean reversion. It might take a while longer, however, to get to 9%.

Pingback: 08/07/17 – Monday’s Interest-ing Reads | Compound Interest-ing!

Pingback: Opening Bell 08.08.2017 - StockViz

Pingback: Happy Hour: Caught Up • Novel Investor

Disappointed to see you repeating the ‘Y2K was a hoax’ thing. There was no disaster because a massive effort was made to fix or replace code that would have malfunctioned.

Pingback: Artikel über Trading und Investments 13.8.17 | Pipsologie

Pingback: Happy Blogiversary to Me (and a prize too) | Above the Market

Pingback: Forecasting Follies 2020 | Above the Market

Pingback: Top Ten Behavioral Biases, Illustrated #2: A Bird in the Hand (Loss Aversion) | Above the Market