As the vast majority of you know, a passive investor most typically looks to hold every security from the market, with the most prevalent of such approaches looking to have each security represented in the same manner as in the market, in order to achieve market returns, usually via index funds. It is a buy-and-hold approach to money management. On the other hand, an active investor is one who is not passive and thus seeks to “beat the market.” It is the art of stock picking and market timing. Because active managers typically act on perceptions of mispricing, and because such misperceptions change relatively frequently, such managers tend to trade more frequently – hence the term “active.”

Passive investing (e.g., indexing) is predicated upon the efficient markets hypothesis. To oversimplify, that hypothesis asserts that because asset prices reflect all relevant information and that investors act rationally on that information, it is impossible to “beat the market” over time except by being extremely lucky. The evidence supporting this idea is surprisingly strong, at least to many.

Most significantly, active managers generally fail to beat their benchmark indices. Indeed, in 2010, only about 25% of active managers outperformed. 2011 was even worse. Data from Morningstar shows that among 4,100 funds that invest in large-cap stocks, only 17% beat the S&P 500 for the year (strictly speaking, all index funds underperformed the market because of costs; however, for these purposes I will treat index funds as having matched the performance of “the market”). That is the smallest percentage since 1997. Moreover, according to Bianco Research, 48% of equity mutual funds underperformed their benchmarks by more than 250 basis points. For example, the Fidelity Magellan Fund underperformed the S&P 500 by close to 14%. Even worse, those few active managers that do outperform in any given year have a very hard time (more here) keeping up the good work.

With correlations among stocks at levels close to their 30-year highs (see below), finding winners is (obviously) exceedingly difficult even if it is theoretically possible.

Bianco Research has observed that from 1996–2008 there were only 12 days (2 up and 10 down.) when more than 490 of S&P 500 Index stocks moved in the same direction on a given trading day. In 2011 alone, there were 15 such days (with a nearly even up/down ratio). In such an environment, finding mispricings is very difficult. Thus, in general, active managers believe that in order to overcome their higher fee hurdle, they need high beta equities that will beat the index in a rally and thus overcome the high fees. But that is a dangerous and flawed strategy.

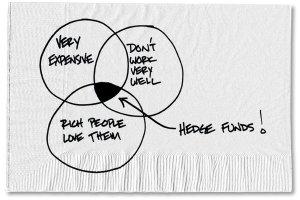

Hedge funds – despite (and in part because of) enormous fees – have also badly underperformed, and they are the most active of active managers. Indeed, since 1998, the effective return to hedge-fund clients has only been 2.1% a year, half the return they could have achieved simply by investing in Treasury bills. Hedge funds are prone to same inconsistencies as more traditional managers too. Legendary hedge fund investor John Paulson generated returns of up to 600% by betting against mortgages in 2008 as the market crashed, but got crushed by huge losses in 2011.

More broadly, the Global Market Index (GMI) —a passive, unmanaged but well diversified mix of all the major asset classes weighted by market values — has outperformed nearly everything else over the past decade (see below), providing a 6.0% annualized total return for the 10 years ending December 31, 2011. That puts GMI in the 89th percentile relative to the roughly 1,200 multi-asset class funds with at least 10 years of history (and thus makes it an even better performer overall than the 89th percentile suggests once survivorship bias is factored in). GMI’s rebalanced and equal-weighted counterparts did even better.

As a consequence of performance numbers like that and the failings of active management, index funds took in a record $76 billion in 2011 and exchange-traded funds, which are predominantly passive, added another $121 billion. Actively managed funds, meanwhile, lost about $9.4 billion, according to Morningstar.

On the face of it, these facts seem to suggest that active management simply doesn’t make sense. At a minimum, it means that any recommendation containing active management must be carefully considered and supported, especially when the advisor is a fiduciary.

Even so, there is an abundance of evidence that markets are less than perfectly efficient. There is no such thing as perfect information. Information can be and routinely is biased, erroneous, flawed and incomplete. More significantly, as individuals and in the aggregate, the idea that we can somehow rationally interpret all that information is – frankly – ludicrous. Behavioral economics teaches us at least that much.

Every year, Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior demonstrates just how irrational investors are. Over the past 20 years the S&P 500 has returned 9.14% annually while the average equity investor has earned only 3.83% per annum, showing how unsuccessful we are at controlling our emotions. We routinely buy high and sell low. It should thus be clear that markets are adaptive and people are plainly and predictably irrational – individually and in the aggregate.

This data also evidences a related point. People find that exploiting the market’s inefficiencies is, at minimum, extremely difficult (partially due to those very same emotional factors), as the failings of active managers demonstrate. Moreover, investment success draws crowds of copycats, making ongoing success a constant challenge. While the efficient market hypothesis is easy enough to falsify, indexing as an investment approach remains excruciatingly difficult to beat.

Active management outperformance can only be predicated upon two things – market timing and/or security selection. With respect to market timing, there is little evidence that it works generally since nobody can foresee the future. Market timing efforts – a forecasting strategy based upon one’s outlook for an aggregate market, rather than for a particular financial asset – simply do not provide good performance. Without reviewing all the research, suffice it to say that both institutional investors (more here, here and here) and individuals consistently fail as market timers. As John Kenneth Galbraith famously pointed out, we have two classes of forecasters: those who don’t know and those who don’t know they don’t know.

The one major exception here (as it relates to performance, not foreseeing the future) is momentum investing (see here and here, for example), including highly quantitative (algorhythmic) investing based upon momentum (such as managed futures). Accordingly, such strategies make good sense in portfolios generally, despite their recent poor performance, assuming their high risk is palatable. Therefore, I tend not to recommend market-timing strategies that are not momentum-based and which do not employ excellent quantitative research.

That leaves us to consider strategies based upon security selection. Unfortunately, most “actively managed” funds are actually highly diversified and thus cannot be expected to outperform. The more stocks a portfolio holds, the more closely it resembles an index. The average number of stocks held in actively managed funds is up roughly 100% since 1980, according to data from the Center for Research in Security Prices. See Pollet & Wilson, “How Does Size Affect Mutual Fund Behavior?” Journal of Finance, Vol. LXIII, No. 6, p. 2948 (December 2008). Large numbers of positions coupled with average turnover in excess of 100% (per William Harding of Morningstar) effectively undermines the idea that such funds could be anything but a “closest index.”

Properly used, diversification is a means to smooth returns and to mitigate risk, as described above. Excessive diversification, on the other hand, is merely (in Warren Buffett’s words), “protection against ignorance.” I prefer taking active risk with vehicles that offer the best opportunities to outperform, including investments that are concentrated and unrestrained. It makes no sense to incur excess costs and to suffer tax inefficiencies to purchase an investment that is, in effect, a closet index.

Numerous studies show that funds which are truly actively managed and more concentrated, outperform indices and do so with persistence. See, e.g., Kacperczyk, Sialm & Zheng, “Unobserved Actions of Mutual Funds” (2005); Cohen, Polk & Silli, “Best Ideas” (2010); Wermers, “Is Money Really ‘Smart’? New Evidence on the Relation Between Mutual Fund Flows, Manager Behavior, and Performance Persistence” (2003); Brands, Brown & Gallagher, “Portfolio Concentration and Investment Manager Performance” (2005); and Cremers & Petajisto, “How Active Is Your Fund Manager? A New Measure That Predicts Performance,” (2007). As summarized by Cremers and Petajisto:

“Funds with the highest Active Share [most active management] outperform their benchmarks both before and after expenses, while funds with the lowest Active Share underperform after expenses …. The best performers are concentrated stock pickers ….We also find strong evidence for performance persistence for the funds with the highest Active Share, even after controlling for momentum. From an investor’s point of view, funds with the highest Active Share, smallest assets, and best one-year performance seem very attractive, outperforming their benchmarks by 6.5% per year net of fees and expenses.”

Accordingly, it is possible to earn higher rates of return with less risk (particularly since risk and volatility are decidedly different things – more on that below) via the judicious use of active management. As the saying goes, nobody is managing the risk of an index. By combining a group of securities carefully selected for their limited downside (think “margin of safety”) and high potential return (think “low valuation” or, better yet, “cheap”), the skilled active manager has a real opportunity to stand out. This approach has practical benefits too in that the resources devoted to the analysis (original and ongoing) of each specific investment varies inversely with the number of investments in the portfolio.

One area for potential outperformance is low beta/low volatility stocks. This surprising finding (since greater return is generally connected with greater risk) has been deemed to be the “greatest anomaly in finance.” As Geoff Considine pointed out at Advisor Perspectives recently, portfolios of either low-beta or low-volatility stocks over the 41-year period spanning 1968 through 2008 would have resulted in annualized alphas of 2.6% and 2.1%, respectively with return “swings” which were also far less extreme than those of the broader market. If the universe of stocks under consideration is limited to the 1,000 stocks with the largest market capitalizations, the low-beta and low-volatility portfolios generated 3.49% and 2.1% in annualized alpha, respectively. Significantly, this approach works well in the large cap space. Moreover, despite rational “copycat risk” fears, there is good research providing reasons to think that this anomaly may well persist. Looking at this opportunity on a risk-adjusted basis only makes it more attractive.

I wish to re-emphasize, however, that success in this arena is extremely hard to achieve and success achieved through good asset allocation can be given back quickly via poor active management. That is why I prefer an approach that mixes active and passive strategies and sets up a variety of quantitative and structural safeguards designed to protect against ongoing mistakes and our inherent irrationality. I want to be most active in and focus upon those areas where I am most likely to succeed. As noted above, I also want to be careful to seek non-correlated asset classes (to the extent possible) in order to try to smooth returns over time and to mitigate drawdown risk.

In the large cap space, markets are relatively efficient and thus alpha-constrained. The mid and small cap sectors provide more opportunities despite some liquidity constraints. International equities tend to provide the best opportunities due to the wide dispersion of returns across sectors, currencies and countries. Indeed, the SPIVA Scorecard demonstrates that a large percentage of international small-cap funds continue to outperform benchmarks, “suggesting that active management opportunities are still present in this space.” Moreover, managers running value strategies outperform and do so persistently, in multiple sectors, especially over longer time periods.

The Fama and French three factor model provides several very helpful pieces of information: expected returns are a function of stocks v. bonds, small cap v. large cap and value v. growth. These three factors explain ~95% of the variation of a diversified portfolio.” Further, each has an expected return premium associated with its higher volatility (if not necessarily risk) but each is unique, so one cannot be lumped in with the others. History and even just the past decade alone suggest that, per Fama and French, a small cap/value equity “tilt” works (see below).

Note that the small-cap value (Russell 2000 Value) and microcap value (Russell Microcap Value) indexes nicely outperformed over the past 10 years (through January 17, 2012). Indeed, the Russell 2000 Value Index has generated a 6.7% annualized total return for that decade, or nearly twice the 3.7% gain provided by the broad large-cap equity market (Russell 1000). It’s also notable that even within the large-cap space, value beat growth. One cannot count on the small-cap and value factors in the short term, and perhaps not even in the long run (remember, investment success draws a crowd and dilutes future success), but they are excellent sources of value (apologies for the pun) today. I focus much of my portfolio attention there.

Active management is not merely predicated upon outperformance. It can also be predicated upon risk mitigation. Yet defining risk can be quite difficult. Traditional quantitative finance equates risk with volatility. By that definition, broad diversification lowers risk because it lowers volatility. I look at risk more practically, however. For me, risk relates more to my chances of losing money – perhaps a great deal of money – over time than the volatility of my portfolio (as Zvi Bodie describes it, uncertainty that matters).

For a deep value investor (and I try to be one), purchasing a stock that has been beaten up and trades at low multiples for its fundamental value may have high volatility but not be all that risky due to a significant “margin of safety.” Grouping such stocks together in a carefully concentrated fashion provides a good opportunity to outperform while mitigating risk. As Warren Buffett put it, “a policy of portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort-level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it.”

Successful managers tend to continue to perform well, particularly in the nearer term, and losing managers tend to continue losing. Even so, the best and most successful investors make mistakes and have down periods – which can last a significant period of time. That’s why so many money managers are so willing simply to mimic the index. Performance which is close to one’s benchmark allows managers to retain assets while significant underperformance will likely cause investors to head for the hills (just ask Bruce Berkowitz – his $7 billion Fairholme Fund went from being the top performing large-cap-value fund in 2010 to the worst-performing fund of 2011 and lost a great deal of assets as a consequence). Being willing to stand out as a contrarian is perhaps as hard as achieving the actual outperformance. That’s why so many money managers remain perfectly willing to act like index investors and hope for roughly index-like returns. For them, it’s a matter of survival.

For advisors, surviving in this business can be a major challenge. Succeeding by actually providing clients with real value is that much more difficult. It demands the bravery to incur much greater risk – but career and reputation risk rather than investment risk. For individuals, it requires the bravery to go against the crowd.

How brave are you willing to be?

Value surely exists, but it can be very hard to find. I suggest using active investment vehicles within portfolios for momentum strategies, focused (concentrated) investments, in the value and small cap sectors (domestic and international), for low volatility/low beta stocks, and for certain alternative investments. Passive strategies can be used to fill out the portfolio to provide broad and deep diversification.

The Value Project

The Value Project (2): Commit to Diversification

The Value Project (3): The Value Proposition

The Value Project (4): Emphasize Process

The Value Project (5): Other Stuff

The Value Project (6): Recognizing Value

Hal Holbrook had a wonderful supporting role in the Watergate saga All the President’s Men, a 1976 Alan J. Pakula film based upon the book of that name by Pulitzer Prize winning reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post. Holbrook played the conflicted, chain-smoking, trench-coated, shadowy source known only as “Deep Throat” (over 30 years later revealed to have been senior FBI-man Mark Felt). Woodward’s meeting with his source when the investigation had bogged down is a terrific scene.

Hal Holbrook had a wonderful supporting role in the Watergate saga All the President’s Men, a 1976 Alan J. Pakula film based upon the book of that name by Pulitzer Prize winning reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post. Holbrook played the conflicted, chain-smoking, trench-coated, shadowy source known only as “Deep Throat” (over 30 years later revealed to have been senior FBI-man Mark Felt). Woodward’s meeting with his source when the investigation had bogged down is a terrific scene.