Note: This is my 1,000th post at Above the Market, which began publication nearly five years ago, in August of 2011. I remain as astonished as ever at the attention it has received. I am grateful to each and every reader. Thank you.

_________________________

In 1821, a man named William Hart dug the first natural gas well in the United States on the banks of Canadaway Creek in my home town of Fredonia, New York. The well was 27 feet deep, was excavated by hand using shovels, and its gas pipeline consisted of hollowed out logs sealed with tar and rags. Natural gas was soon transported to businesses and street lights in town. These lights frequently attracted travelers, often causing them to make a significant detour to see this new “wonder.” Expanding on Hart’s work, the Fredonia Gas Light Company was formed in 1858, becoming the first American natural gas company.

Gas lighting is thus an inexorable part of my personal history. But I’m even more interested in gaslighting.

In the 1938 play Gaslight, a murderous husband is intent on inducing instability in his wife in order to accommodate his venality. When she notices that he has dimmed the gaslights in their house, he tells her she is imagining things—that they are as bright as ever – as a way to get her to question her senses and her sanity. The British play became a classic 1944 American film from George Cukor, starring Ingrid Bergman as the heroine and Charles Boyer as her abusive spouse, out to convince her that reality is not what she perceives. In this sort of story, our most dangerous enemies are always those closest to us, masquerading as lovers and friends. Gaslight reminds us how uniquely terrifying it can be to mistrust the evidence of our senses and of what we know to be true.

Taking off from the film, “gaslighting“ in contemporary usage means a form of intimidation or psychological abuse whereby false information is systematically presented to the victim, causing him to doubt his own memory, perception or even his sanity. As in the movie, gaslighting is a hallmark of domestic abuse, but one can see its use and impact almost everywhere. I wrote much of this while in Washington, D.C., perhaps the world’s gaslighting capital.

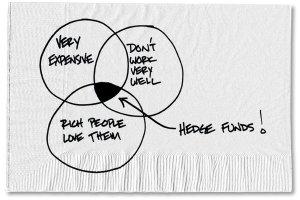

In the investment management world, the overarching priority for the vast majority of money managers is to gather assets and revenues and only peripherally to provide quality performance for investors. Gaslighting is routinely used to try to obscure those priorities and to convince investors that, despite the reality of what they see, investing in product X or with firm y is a smashing good idea. Continue reading

There is a new and growing movement in our industry toward so-called evidence-based investing (which has much in common with

There is a new and growing movement in our industry toward so-called evidence-based investing (which has much in common with

As the great Mark Twain (may have) said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” That’s particularly true in the investment world because we know, to a

As the great Mark Twain (may have) said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” That’s particularly true in the investment world because we know, to a